The professionals. This includes everyone who makes at least half of his or her living from astronomy. Some teach college. Others do research. The latter have specialties like astrometry that occupy most of their attention.

The telescope makers and gadgeteers. This breed once made up a large proportion of astronomy hobbyists. They grind mirrors, build fantastic telescopes, and haul them to star parties. They are hands-on and innovative. Many are first-adopters of new technology. They enjoy looking at telescopes as much as through them.

The amateur specialists. These include variable-star observers, satellite trackers, and comet hunters. They produce scientifically useful data.

The backyard amateurs. These people think astronomy is cool. Many of them know a lot. They enjoy reading about science. Some own telescopes.

The beginners. Members of this group can be any age and just awakened to astronomy. They don’t know much yet but find everything exciting.

The photographers. These artists create and share astrophotography techniques. Theirs is a vast kingdom of skill and patience. The rest of us sit back and enjoy what they do.

The sci-fi crowd. These folks mostly care about hypothetical aspects like wormholes and tachyons. They never tire of doors into other dimensions and folded space. They mainly focus on astronomy that pertains to such possibilities.

Space travel advocates. These romantics, who include members of The Planetary Society, want to colonize other worlds. They primarily concentrate on Mars, asteroids, and jovian moons, and they actively push for NASA funding.

The nuts and visionaries. Every science magazine gets letters “disproving” relativity or offering a “theory of everything.” Some are absolutely brilliant. Others are from people who believe an imminent asteroid collision will destroy Earth and NASA is covering it up. The correspondence sometimes includes detailed math and physics. These folks are convinced they’ve found something no one else knows. A few may even be right.

ARE YOU?

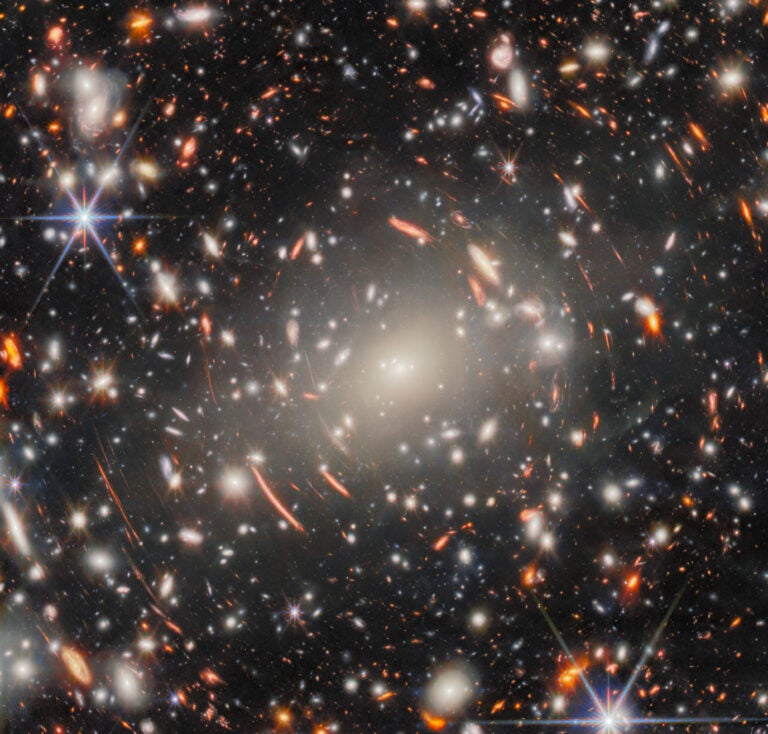

The cosmology zealots. Their obsessions are the “Big Picture” and the farthest-out models. Throw them a “colliding branes” or “multiverses” hypothesis, and they’ll lap it up. They are cerebral, speculative, and open-minded. They value original thinking and novel possibilities over hard data.

The spouses. They get dragged to star parties, astronomy tours, and public talks — and sort of enjoy them.

The navigators. Mostly pilots and yachtsmen, they focus on the night sky because they enjoy the ancient art of hands-on celestial navigation.

The people who don’t have a clue. Like my Aunt Shirley. This is the vast majority of the world. This isn’t a put-down; folks have different interests. Still, it’s a fact that 99 percent of the population cannot name the brightest star, the closest planet, or the universe’s most common element. The cosmos just doesn’t interest them.

There’s very little crossover. You might belong to more than one group but rarely, say, five. For example, many of you probably would go out of your way to see a total solar eclipse or an auroral display. Yet a top British solar researcher I know has never bothered seeing an eclipse. For many professionals, actual sky spectacles have a low priority.

Astrophysicists are skeptics (properly so) and usually shrug off speculative theories, especially those claiming to overturn established models. Unlike many hobbyists, they are comfortable with calculus and complex statistical analyses.

Another dichotomy: Many amateurs and some professionals are knowledgeably at home under the stars, but, in my experience, most researchers don’t know the actual night sky at all. They really don’t care how to find the place in the sky where the galaxy they’re studying lies.

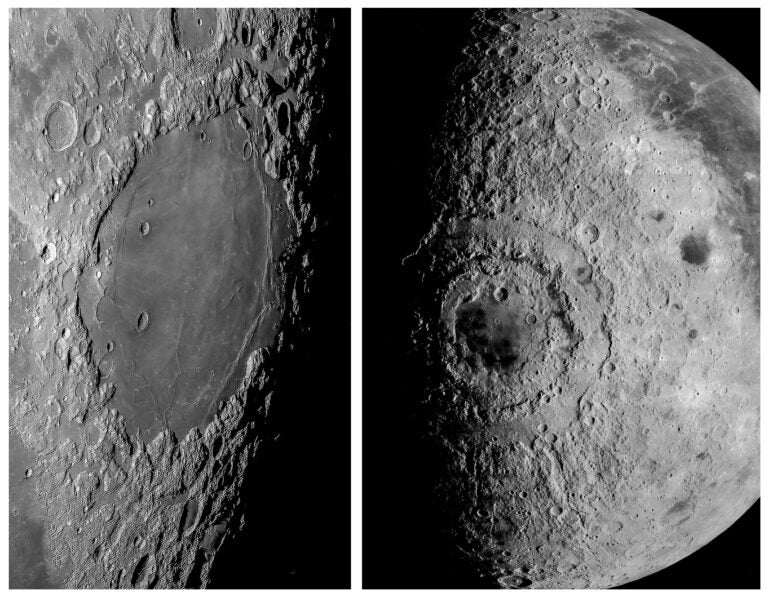

As for cosmologists and theoreticians, they’re model-oriented. In their world, paradigms sometimes merrily shift. In sharp contrast, planetary scientists never feel the slightest impulse to create imaginary dimensions to make stuff work. Planetary science is totally down-to-earth.

We’re a motley group. Yet the cosmic piñata contains such a vast assortment of goodies that cool stuff keeps tumbling out no matter what we’re seeking.

Our family even includes Aunt Shirley, who (honest-to-gosh true story) once asked me, “How were the astronauts able to steer around all those stars when they went to the Moon?”

Sharing that during a lecture makes all the various group members smile (yes, even inmates, since I taught college astrophysics for four years at a maximum security prison). We may run the spectrum, but we’re bonded by no fragile epoxy. We’re linked by the fabric of the universe.

Contact me about my strange universe by visiting http://skymanbob.com.