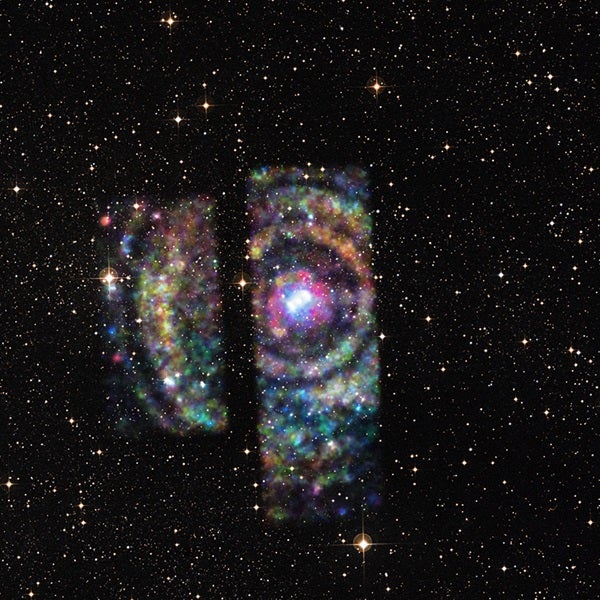

A few months ago astronomers at the Subaru Telescope observed light from a “new star” that astronomer Tycho Brahe and others saw November 11, 1572. What Brahe observed as a bright star in the constellation Cassiopeia, outshining even Venus, actually was a rare supernova event where a star’s violent death sends out a bright energy outburst. He studied the brightness and color of the “new star” until March 1572 when it faded from view. The remains of this milestone event are seen today as Tycho’s supernova remnant.

A team of international astronomers at Subaru recently completed a study that focused on ‘light echoes’ from Tycho’s supernova to determine its origin and exact type, and relate that information to what we see from its remnant today. A ‘light echo’ is light from the original supernova event that bounces off dust particles in surrounding interstellar clouds and reaches Earth many years after the direct light passes. This team used similar methods to uncover the origin of supernova remnant Cassiopeia A in 2007.

Lead project astronomer at Subaru, Tomonori Usuda, said “using light echoes in supernova remnants is time-traveling in a way, in that it allows us to go back hundreds of years to observe the first light from a supernova event. We got to relive a significant historical moment and see it as famed astronomer Tycho Brahe did hundreds of years ago. More importantly, we get to see how a supernova in our own galaxy behaves from its origin.”

On September 24, 2008, the team used the Faint Object Camera and Spectrograph (FOCAS) instrument at Subaru to break apart the light echoes into the signatures of atoms (spectra) present when Supernova 1572 exploded. The signatures reveal all the information about the nature of the original blast. The results showed clear absorption of once-ionized silicon and absence of the hydrogen H-alpha emission. The findings are typical of a Type Ia supernova observed at maximum brightness of its outburst.

During the study, the astronomers tested theories of the explosion mechanism and the nature of the supernova progenitor. For Type Ia supernovae, a white dwarf star in a close binary system is the typical source, and, as the gas of the companion star accumulates onto the white dwarf, the white dwarf is compressed and sets off a runaway nuclear reaction inside that leads to a cataclysmic supernova outburst. As Type Ia supernovae with luminosity brighter/fainter than standard ones have been reported recently, the understanding of the supernova outburst mechanism has come under debate. To explain the diversity of the Type Ia supernovae, the Subaru team studied the outburst mechanisms in detail.

The group discovered Supernova 1572 shows indications of a nonsymmetrical explosion, which, in turn, puts limits on explosion models for future studies. In addition, follow-up comparisons with template spectra of Type Ia supernovae found outside our Galaxy show that Tycho’s supernova belongs to the majority class of Normal Type Ia, and it’s now the first confirmed and precisely classified supernova in our galaxy. Type Ia supernovae are the primary source of heavy elements in the universe and play an important role as cosmological distance indicators, serving as ‘standard candles’ because the level of the luminosity is always the same for this type of supernova.

This observational study at Subaru established how light echoes could be used in a spectroscopic manner to study supernovae outburst that occurred hundreds of years ago. The light echoes, when observed at different position angles from the source, enabled the team to look at the supernova in a three dimensional view. For the future, this 3-D aspect will accelerate the study of supernova outburst mechanism based on their spatial structure, which has been impossible with distant supernovae in galaxies outside the Milky Way.