British astronomers and father-son duo William and John Herschel pointed their telescopes all over the sky in the 18th and 19th centuries, taking samples of objects they called “nebulae.” In using the word nebula, they didn’t always mean what we do today. They merely meant a celestial object that wasn’t a comet but nonetheless appeared fuzzy. And they believed all these nebulae lay within the Milky Way.

In their 1864 catalog, John noted that more nebulae populated the area around the constellation Virgo. (French astronomer Charles Messier also had noted such structure a century earlier.) The reason, though, remained nebulous.

In 1920, the “Great Debate” attempted to resolve the nature of nebulae. American astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis argued about whether these objects represented nearby cloudiness or whether they were galaxies in their own right, rendered fuzzy by distance. The latter interpretation won out. But why did these galaxies cluster around Virgo? Was it chance or something more?

In the 1950s, French astronomer Gérard de Vaucouleurs observed how these Virgo galaxies traveled through space. Curiously, they seemed to be moving away from us at the same speed and lay fairly close to one another and to us. They were, in astronomy parlance, “dynamically related.” In 1953, he christened this crowd the Local Supergalaxy. Five years later, he changed it to the Local Supercluster.

As telescopes became more powerful, astronomers could take larger surveys, cataloging more galaxies and their motions. These pixeled together a bigger picture: a concentration of galaxies along a plane in space. Just as most of the Milky Way’s stars reside in a thin equatorial disk, so most of the galaxies in the Local Supercluster lie along its equator. Science had spoken — stars cluster in galaxies, galaxies cluster in clusters, and clusters cluster in superclusters. And the center of our supercluster shared a spot in the sky with Virgo.

If you placed 1,000 Milky Ways end to end, they would span 100 million light-years — the size of our supercluster. Two-thirds of the bright galaxies live in a disk near the equator, around which the remaining third spread like the globular clusters around our galaxy. In total, a mass equivalent to 10 quintillion Suns fills our cosmic supercity. Much of that mass, however, isn’t luminous. Just as dark matter dominates the universe, it also fills the supercluster. Still, lots of pretty light-emitting objects live next door, cosmically speaking.

Closest to us, perhaps 11 million light-years away, live the Maffei I and II groups. Although nearby, they went unnoticed until 1968 because they lie right behind the Milky Way’s plane, so the material that makes up our home drowns out the light from Maffei’s constituents. But Italian astronomer Paolo Maffei noticed something strange when he looked at IC 1805 (a true nebula). A nearby object shone in infrared light. He guessed it was a galaxy, obscured by the Milky Way. In the past 20 years, astronomers have found 17 more associated galaxies.

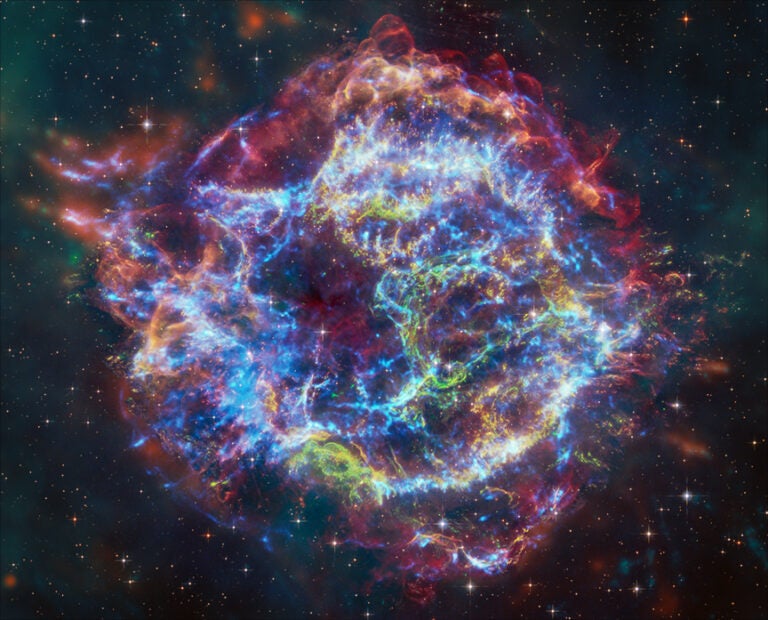

A million light-years farther away, the Sculptor Galaxy Group is easier to pick out. From 2011 to 2013, a group of astronomers led by Tobias Westmeier of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Australia studied how high-velocity clouds (HVCs) of hydrogen enrich member galaxies NGC 55 and NGC 300. HVCs don’t rotate with galaxies; instead, they come from outside and stream in like missiles. Astronomers believe they may provide fuel to produce more stars as galaxies run out of their own gas. But HVCs have to come from somewhere.

At the time of Westmeier’s study, two theories dominated, and he wanted to find which was true. In one, HVCs are clumps of gas shot out of a galaxy by supernovae; in the other, they are dwarf galaxies dominated by dark matter and gas that never formed stars. “Due to its proximity, the Sculptor Group was the most obvious choice for this study,” he says, “enabling observations at sufficient resolution and sensitivity to detect potential HVCs.

The big surprise from the study, however, was about wonkiness in the big galaxies’ gaseous disks. They appear to wobble as they travel through space under the influence of a force called ram pressure. This could happen only if the galaxy slammed into a dense intergalactic medium. While astronomers know that large clusters bathe in dense soups of material, they thought smaller groups sat in thin broths.

The pressure blows gas away, meaning stars can’t form as well — or at all in the case of small satellites. “As gas constitutes the fuel for future star formation, its removal could potentially shut down star-formation activity in dwarf galaxies living in group environments,” says Westmeier.

This discovery helps solve a mystery called the “missing satellites problem,” which arose about 15 years ago when computer simulations showed that galaxies like the Milky Way should have more dark dwarf-sized companions than they do. “This discrepancy suggests that either there is something wrong with the simulations or some mechanism has prevented the majority of dark matter halos from turning into proper galaxies,” says Westmeier. If pressure strips gas away, as it seems to in the Sculptor Group, small galaxies wouldn’t be able to form stars, meaning the satellites aren’t missing — they’re invisible.

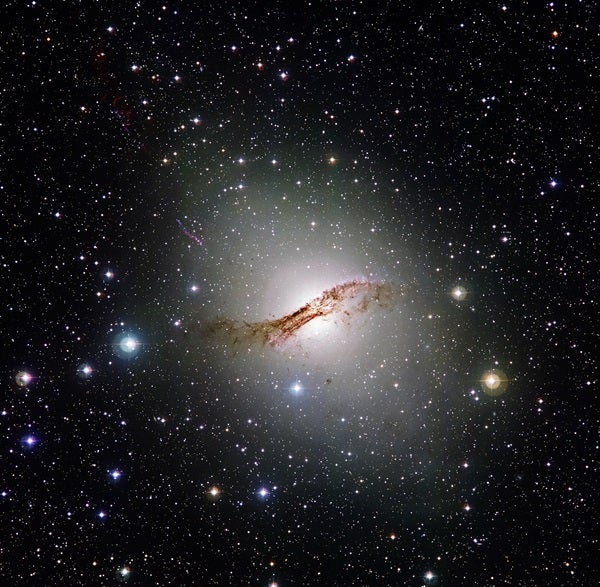

The Centaurus A Group lies at a similar distance as Sculptor, some 12 million light-years from Earth. The group’s dominant member, Centaurus A, is the closest radio galaxy. This massive object swallowed a spiral galaxy about 500 million years ago. The digestion is ongoing, though, and it causes radio waves to blast into space. Centaurus A serves as an example of what could ensue when the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies collide 4 billion years from now.

A more visually recognizable crowd — the M81 Group — resides at the same distance. Located inside the boundaries of Ursa Major and Camelopardalis, it contains 1 trillion solar masses and 34 known galaxies, the most famous of which are M81 and M82. The two tug on each other, which has turned M82 into a star factory. The galaxy’s center glows 100 times brighter than the Milky Way’s as hydrogen gas falls from intergalactic space toward the gravitational hub.

The galaxy causing some of this ruckus, M81, holds the title of “Biggest Galaxy in its Group.” At the center of its perfect spiral arms lurks a supermassive black hole weighing 70 million solar masses.

In contrast to the order in the M81 Group, the Canes Venatici I Group seems chaotic. Located 15 million light-years away in the constellations Canes Venatici and Coma Berenices, this group’s members are bound only loosely to one another. Not all of its approximately 20 galaxies have settled into stable orbits, and they seem to be just weakly connected gravitationally.

Several million light-years farther out and back in the direction of Ursa Major, the M101 Group has the same loose, disconnected air. This group’s namesake keeps the family together. Most of the other galaxies in the group are merely companions of this Milky Way twin.

M101 spans 170,000 light-years, has tightly wound spiral arms, and holds 100 billion solar masses’ worth of material.

Less than 20° to the southwest, we find the Canes Venatici II Group. Thirty million light-years from home, this group’s largest and most famous member is M106. Water vapor in this galaxy pulses out microwave radiation, creating a giant microwave equivalent of a laser called a megamaser. Astronomers used the water megamasers orbiting M106’s supermassive black hole to directly measure its distance.

The galaxy also contains visible Cepheid variable stars, “standard candles” whose predictable brightness changes astronomers also can use to tabulate distance. These stars dim and brighten periodically like seizure-inducing Christmas lights, and the period gives away the star’s intrinsic luminosity. By comparing this to the star’s observed brightness, astronomers can calculate how far away it is. Thus, the water megamasers and Cepheid variables in M106 help scientists calibrate the cosmic distance scale.

The M96 Group in Leo lies some 36 million light-years away and has a number of big, bright galaxies — 12 with diameters above 30,000 light-years. In 2010, it also helped astronomers investigate how galaxies form thanks to a ring of chilly gas 650,000 light-years wide that encircles the group. For 30 years, no one understood where it came from or what exactly it was.

Then a team led by astronomers at Lyon Observatory decided to tease out the ring’s nature. The researchers believed that it might reveal itself to be “primordial gas,” gas that has never lived inside another galaxy and can’t, in its current form, transform into stars. For galaxies to form, astronomers think cold primordial gas has to fall into the system, like high-nutrition food to help fuel the growth of early years. But no telescope had seen such old-school atoms around a growing galaxy. The Leo Ring, these scientists thought, might be just that.

But when they turned their telescope on it, they found bright optical light, the kind that massive young stars emit. Primordial gas, by definition, cannot create such stars. They had a new mystery.

Using computer simulations, the team discovered that the ring represents a scar left over from a colossal collision: NGC 3384, a central elliptical galaxy, and M96, a peripheral spiral, smashed into each other more than a billion years ago. The gas from one blew away, eventually forming the ring.

The biggest and baddest

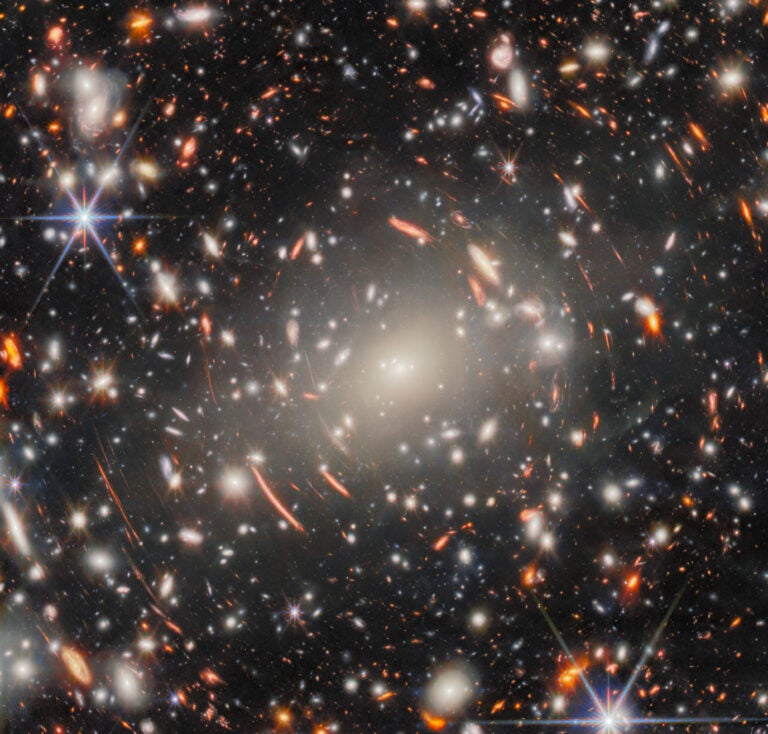

The Virgo Cluster, the most significant collection of galaxies with the home address “Local Supercluster,” has a center some 55 million light-years away. As its name suggests, you can find it in the direction of the constellation Virgo. Compared to the meager dozens of galaxies in the previous groups and clusters, Virgo has 1,300 — and maybe even 2,000 — constituents. They add up to 1.2 quadrillion solar masses spread across 7.2 million light-years.

In between these galaxies roams a rogue set of intergalactic stars — up to 10 percent of the cluster’s total. Globular clusters, dwarf galaxies ripped from parents, and at least one star-forming region also populate the intergalactic region. Hot X-ray-emitting gas permeates the space where these orphans live.

The Virgo Cluster is so big that it actually has subclumps: Virgo A, Virgo B, and Virgo C. Virgo A dominates, encompassing 10 times as much mass as the other two. The three eventually will merge into a single giant cluster. Because these subgroups have yet to coalesce, astronomers suspect Virgo is young and still figuring out its identity.

Because Virgo has so many galaxies at approximately the same distance from Earth, astronomers use the cluster as a laboratory to study galaxy evolution. Just as an alien visitor would learn more about human development by looking at a stadium full of different people than at a single family, so too can astronomers learn more about galaxies from a huge batch like the one in Virgo.

One thing they learned recently deals with star formation — more specifically, stars that are not forming as fast as many expected. A 2014 study found that turbulence — the kind that shakes airplanes — in the center of Virgo shakes up star-making gas, keeping it hot for billions of years. That turbulence, which comes from active black holes in galaxy centers shooting out powerful jets, prevents the gas from becoming stable enough to form stars.

“The energy in such slow motions is more than enough to stop gas from catastrophic cooling and star formation,” says lead researcher Irina Zhuravleva of Stanford University in Palo Alto, California. Understanding why stars stop forming at the centers of galaxies and clusters helps astronomers understand how their lives progress and how the life of our own galaxy and group might unfold.

Even farther out, a 59-million-light-year jaunt, lies the Dorado Group. This large collection comprises 70 galaxies in the direction of the southern constellation Dorado the Dolphinfish (a species that appears on menus as “mahi-mahi”). One of its most prominent members, NGC 1483, shows a luminous central bulge and jumbled spiral arms that host bright star-forming regions and young star clusters.

At approximately the same distance but in the direction of Ursa Major, two groups form a defined band. Most of its major galaxies are spirals, and these combine with the minor ones to produce 30 percent as much light as the Virgo Cluster. Thirty percent may not sound impressive, but consider that the Ursa Major groups contain just 5 percent of Virgo’s mass.

Thirty-two galaxies call the Ursa Major North Group home, including the bright spirals NGC 3631, NGC 4088, NGC 3953, and M109. The last of these looks most similar to the Milky Way. Of all 109 objects in the Messier catalog, it lies farthest away, meaning that 18th-century telescopes couldn’t decipher things beyond this point. Now, however, large scopes on Earth and in space give us glimpses of galaxies billions of light-years more distant.

Moving targets

But classifying those galaxies into categories has always been a problem. They orient themselves differently relative to us, and a face-on spiral looks quite different from one seen edge-on. We only have a 2-D sense of galaxies, as if they’re projected on a screen, rather than a true 3-D picture. The problem is particularly acute for disk-shaped galaxies, such as spirals, and spheroidals. You can tell the difference, though, by watching how their stars move. If they rotate slowly and disorderly, they’re spheroidal. If they rotate fast and in an orderly manner, they are disk galaxies.

A team of astronomers led by Nicholas Scott of the University of Sydney in Australia set about to study the stellar motions in the Fornax I Cluster, 62 million light-years away. They found that 93 percent of the cluster’s galaxies were fast rotators (spirals) and just 7 percent were slow rotators (spheroidals). Combining this study with those of other clusters, including the larger one in Virgo, Scott’s team found that the spheroidals tended to hover near a cluster’s center — either because they began there or migrated there.

“One of the long-debated ideas is the question of nature versus nurture in galaxy evolution,” says Scott. Is how a galaxy looks today totally determined by its properties in the early universe, or do its surroundings play a role too? “This study shows that, for at least some galaxies, the environment does play a major role.” He adds that many questions still exist, which further cluster studies can answer.

More questions always exist about the cosmos — its stars, galaxies, groups, clusters, superclusters, and beyond. And because the universe is organized into superclusters, their constituents stay “close” together. Astronomers can swing their telescopes and find a stadium alive with variety. They learn not just what the more distant universe is like, but also what it used to be like, what it will be like, and what has happened and will happen even closer to home.