Iye is one of many astronomers working in Japan; a country that, as we’ll soon see, is emerging as an astronomical powerhouse.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Trying to quiet my grumbling stomach, I’ve happily accepted Iye’s offer to join him at Cosmos Lodge, the cafeteria of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ). But the plan hits a snag when I find myself face to face with the cafeteria’s vending machine-style ordering system. Seeing my confusion at the panel of mysterious buttons and kanji, Iye helps me deposit some yen and order noodle soup. Together, we bring our tickets to the lunch counter, where we are rewarded with steaming bowls of salty, meaty broth.

From imaging exoplanets to solving a solar mystery, mapping dark matter to investigating the origins of the universe, NAOJ scientists are taking on some of the hottest questions in astronomy today. And few would make a better lunchtime companion than Iye, whose discovery in 2006 of the most distant galaxy found at that time gave scientists a picture of the universe as it appeared nearly 12.9 billion years ago. He broke his own record with the discovery of an even more distant galaxy in 2012.

“Now I’ve been defeated by another group,” he says with a chuckle. “But it’s OK. It’s a very interesting competition.”

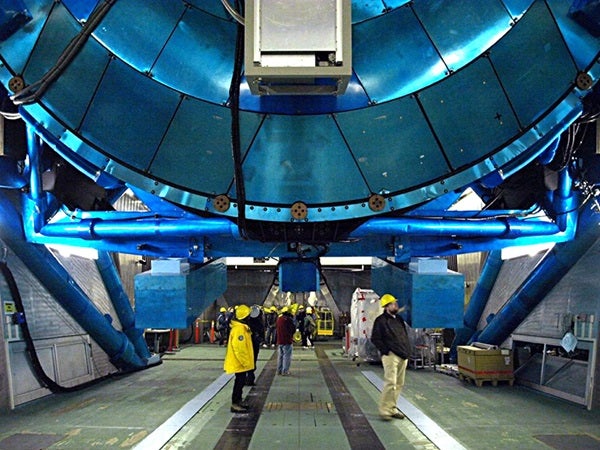

Iye’s breakthrough came in developing narrow-band filters to detect Lyman-alpha photons from galaxies at the outer reaches of the universe. Using these filters with Japan’s Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, his team completed a detailed survey of primordial galaxies. Their finding that galaxy density decreases significantly between 12.8 billion and 12.9 billion years ago, pinpointing the start of the cosmic dawn, earned Iye the 2013 Japan Academy Prize.

“We are just like archaeologists mining fossils to study the history of the Earth,” he says. “We are using telescopes to mine past galaxies to study the history of the universe.”

You might trace the origins of modern-day astronomy in Japan to the year 1782, when the tenmonkata, or official astronomer, was installed by the shogun at Asakusa Observatory. An observatory was later built for students at the University of Tokyo, and the Tokyo Astronomical Observatory was founded in 1888, with the mission to establish latitude and longitude, and keep the correct date and time by observing the stars. The observatory was moved in 1924 to its current site at Mitaka, a city on the outskirts of Tokyo, and it was reorganized as the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan in 1988.

Today, NAOJ still keeps Japan’s official time and calendar. But with observatories located around Japan, as well as tools like Subaru, the Hinode space telescope, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) radio telescope in Chile, and the “ATERUI” supercomputer, NAOJ scientists are also investigating some of the universe’s biggest mysteries.

Direct observation of distant worlds

For Motohide Tamura, it wasn’t enough just to know an exoplanet was out there. He wanted to actually see it.

But even though nearly 2,000 exoplanets have been discovered with tools like the Kepler Space Telescope, images of these distant worlds have remained elusive, with just a handful of extrasolar planets observed through direct detection to date. Tamura hoped to fill that gap with SEEDS, Strategic Explorations of Exoplanets and Disks with Subaru. The five-year, direct-detection survey of giant planets and circumstellar disks — dust clouds around young stars from which planets form — around 500 nearby stars concluded in January 2015, resulting in the direct imaging of four planets, three brown dwarfs, and more than 30 protoplanetary disks, says Tamura, the principal investigator on the project.

SEEDS measured thermal emissions from planets and disks to create an image of the objects. The technique paves the way for astronomers to learn more about these worlds than is revealed through indirect detection, which typically tells scientists little more about a planet than its location and possible mass. “Most important for direct imaging, we can measure the color of the planet, and eventually we can do spectroscopy of the planet itself,” Tamura notes.

Discoveries included a Jupiter-like planet orbiting 40 astronomical units from its star (an AU is the average distance between Earth and the Sun) — one of the lowest-mass planets with one of the closest orbits yet observed. “It has a blue color, compared to the other directly imaged planets, which means . . . the upper atmosphere is relatively clean or free of dust, and the temperature of the atmosphere is very cold,” says Tamura. Scientists also detected the signature for methane in the planet’s atmosphere.

The survey’s observations offered astronomers a chance to study circumstellar disks as well, including the chance to observe gaps and tendrils Tamura calls “signatures of an unseen planet” within the disk structure.

SEEDS isn’t the only program offering new insights into planetary formation. Misato Fukagawa is among the NAOJ astronomers tapping ALMA at NAOJ’s Chile observatory to study protoplanetary disks. The powerful radio telescope allows astronomers to look beyond a disk’s dusty outer surface to see the larger masses and structures within. One disk Fukagawa studied had the appearance of “two bananas” encircling a central star when observed in infrared. But when she looked at the same object with ALMA, it had more of a horseshoe shape.

“We think that what we saw in infrared is light scattered by the solid particles in the upper surface of the disk. But with ALMA, we think we can see the density structure in the midplane of the disk,” she says. “From this structure, we think a little bit of growing material is distributed in this shape.”

Astronomer Eiichiro Kokubo was also fascinated by planetary science, but it led him down a different path. Kokubo wanted to watch a solar system actually taking shape. For that, he turned to a supercomputer.

“It’s very difficult to investigate the formation of planets by telescope because the timescale is very long, and the planets are very small and far away,” he says. “But what we can do is a numerical experiment. We can see how a protoplanetary disk evolves with time, or how the planets form. We can do this only with numerical simulations because we cannot see them directly.”

Today, Kokubo is director of NAOJ’s Center for Computational Astrophysics (CfCA), which operates the Cray XC30 supercomputer ATERUI, the most powerful supercomputer in the world dedicated exclusively to astronomy. Alongside observational and theoretical astronomy, Kokubo calls simulation astronomy “the third way of astronomical research.”

“The solar system was formed 4.6 billion years ago. We cannot see it. But we can set up a virtual universe in the computer, using laws of physics,” he says. “We often say supercomputers are a kind of theoretical telescope to see unseen things.”

The center’s role as a branch within NAOJ gives it a unique position to work closely with observational and theoretical astronomers, Kokubo notes. Computing time is available not only to native and foreign astronomers in Japan, but also to Japanese astronomers working abroad.

CfCA completed a major upgrade of ATERUI last year, increasing performance from 502 teraflops to 1.058 petaflops, giving it the capability to perform 1,000 trillion calculations per second. The added speed will allow ATERUI to serve more researchers, as well as to take on even more complex simulations, Kokubo says.

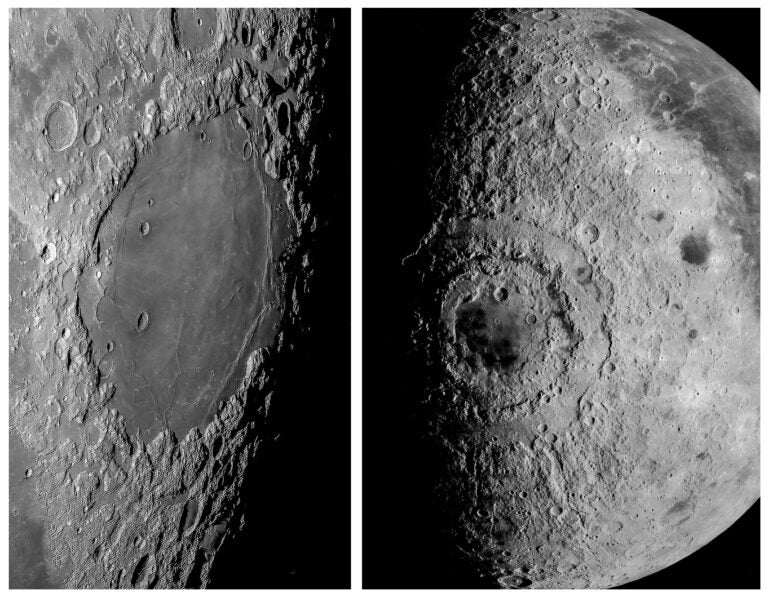

An early achievement for CfCA was its work on a project that simulated the so-called “giant impact scenario,” showing how a massive collision with Earth created a disk of rock and debris that quickly formed the Moon. The process had been theorized in the 1970s as a model, but had never been tested. “From this simulation, we could understand how the Moon is formed from the impact-generated disk, and also why we have only one moon,” Kokubo says.

More recently, ATERUI was used to create a high-resolution simulation of a supernova. “This is the most inner part of a supernova explosion, which we cannot see from observation,” he says. The simulation was so complex, it required the use of the entire supercomputer at once, something CfCA schedules for large projects about once a month.

Kokubo says working with simulations has allowed him to fulfill not only his scientific ambitions, but also a childhood dream. “When I was an elementary student, I thought I wanted to be an explorer,” he says. “When I’m looking at the solar system, I can’t physically be an explorer, but I can do it with supercomputers. It’s a numerical exploration of the universe.”

Like many other solar physicists, Patrick Antolin wanted to figure out why the Sun’s corona was so hot. While the solar surface is a relatively cool 6,000° C (about 11,000° F), the Sun’s atmosphere rises to more than a million degrees Celsius. Now Antolin and other NAOJ scientists working with the Hinode spacecraft may be helping to solve the mystery, in partnership with NASA’s IRIS mission and the ATERUI supercomputer.

In August, the team published a paper in The Astrophysical Journal, offering new evidence supporting the theory that the heating comes from magnetic waves in the form of resonant absorption, a process in which two different magnetic waves resonate with each other, causing one to get stronger.

The process had been theorized but never directly observed, Antolin says. “This work shows it for the first time in a direct way,” he says. “It’s the first evidence of a coronal heating mechanism in action.”

To get the results, the team used Hinode to measure the waves’ side-to-side motion and combined the data with IRIS’ observations of the waves’ twisting motion to get a three-dimensional picture. By running the results through a simulation in ATERUI, they were able to show how the movement resulted in an unusual form of turbulence not seen on Earth that released energy into the atmosphere.

Antolin compares the turbulence to a spoon as it stirs milk into a cup of coffee. Ordinarily, the spoon creates a small wake that would curl back in a half-circle, and when the spoon stops, so does the turbulence. But the magnetic turbulence they observed was different: When a magnetic field line stops moving, the plasma around it moves at maximum speed in the opposite direction.

The finding “was an essential part of the puzzle,” he says. “Large quantities of energy can pass from the magnetic field into the plasma due to this turbulence.”

The team observed the phenomenon in a solar prominence, but Antolin says there’s no reason to believe it would not be found in other structures of the Sun, and current research will investigate whether it occurs in spicules, which are small jets of gas emitted by stars.

“I think this is already very strong evidence that this is happening all the time,” he says.

Physicist Satoshi Miyazaki still hopes to understand the nature of dark matter someday. But for the time being, he’s using the little that’s known about dark matter to help crack an even bigger mystery: dark energy.

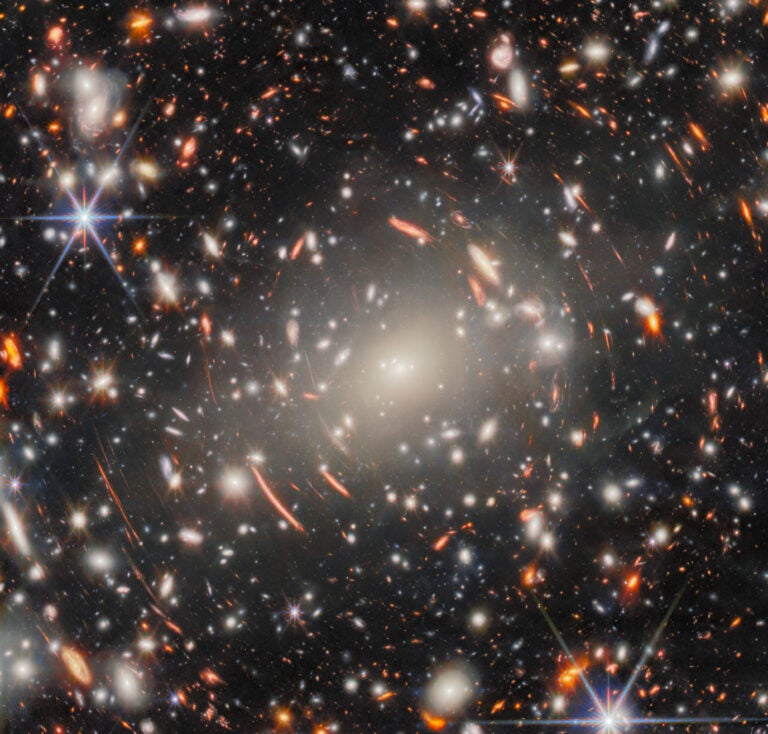

Miyazaki heads the NAOJ project that uses a powerful new camera to make a comprehensive study of how dark matter is distributed across the universe. The so-called “dark matter map” will offer scientists important clues about how the universe expanded, which in turn will help explain the role of dark energy.

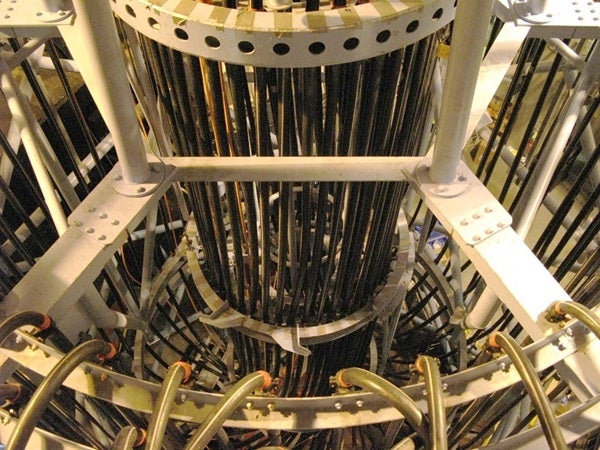

To detect the presence of dark matter and measure its mass, Satoshi and his team designed a high-resolution, wide-field camera for the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii. With the Hyper-Suprime Cam, they are able to create a survey of galaxies across a broad section of the sky, capturing extremely precise images of even very faint, distant objects.

Although dark matter itself is invisible, the gravity created by its mass bends the light passing through it, like the lens of a magnifying glass. “Suppose there’s a dark matter concentration somewhere between us, the observer, and a far, faint galaxy,” Miyazaki says. “The shape of the background faint galaxy is warped by the dark matter concentration through gravitational lensing. If we can measure the pattern of the warp of the galaxy, then that pattern tells us how much dark matter is between the galaxy and us, and how it’s distributed, and where.”

The five-year dark matter survey, which began in January 2012, will eventually observe 1,400 square degrees of sky over 300 observing nights, he says.

The project will run parallel with the five-year Dark Energy Survey, which launched in 2013, he notes. But while the U.S.-led project will survey a wider field of sky, 5,000 square degrees, Miyazaki says NAOJ’s survey has an advantage in the superior sensitivity of the Hyper-Suprime Cam, which can detect fainter, more distant galaxies. “If we have a larger number of galaxies, we can get a higher-resolution dark matter map,” he says.

While the survey’s goal is to shed light on the mystery of dark energy, Miyazaki says his passion has always been to understand dark matter itself. Now that the survey is underway, he plans to take a closer look at some of the large dark matter clusters being detected, to study how mass is distributed within the cluster itself. “If we have a much deeper and much finer image of the dark matter cluster, that tells us about the nature of dark matter,” he says. “That’s my next target.”

With access to powerful observatories like Subaru and ALMA, not to mention the world’s most powerful astronomical supercomputer, it’s clear Japanese scientists are poised to play a role in some of the 21st century’s most significant astronomical discoveries. From exoplanets and ancient galaxies, to solar physics and the mysteries of dark energy and dark matter, NAOJ astronomers are investigating the hottest questions in the universe today.