— Quintus Smyrnaeus, The Fall of Troy

A bit ignored at first

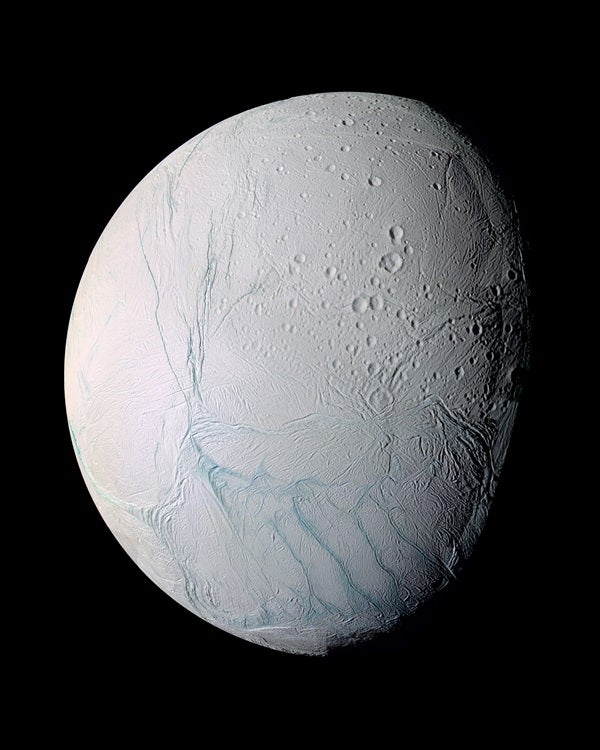

English astronomer William Herschel discovered Enceladus in 1789, but it remained an enigma until the Cassini mission began orbiting Saturn in 2004. Prior to Cassini, Enceladus was a bit ignored. We didn’t know liquid water could exist that far out in the solar system, so why would anyone be that interested in another boring, dead ball of ice?

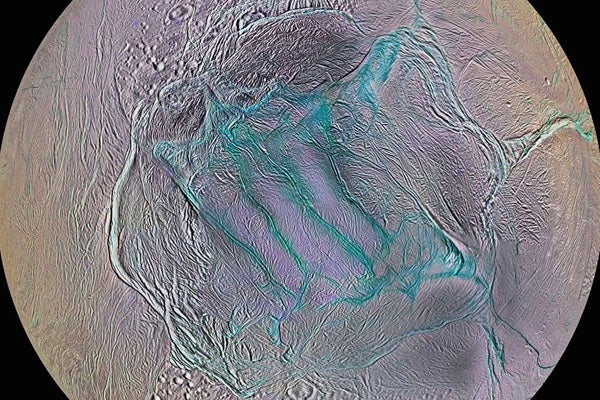

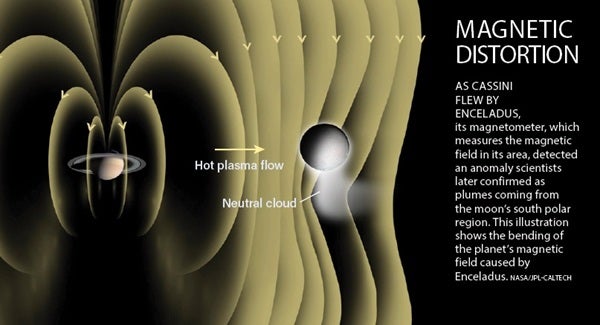

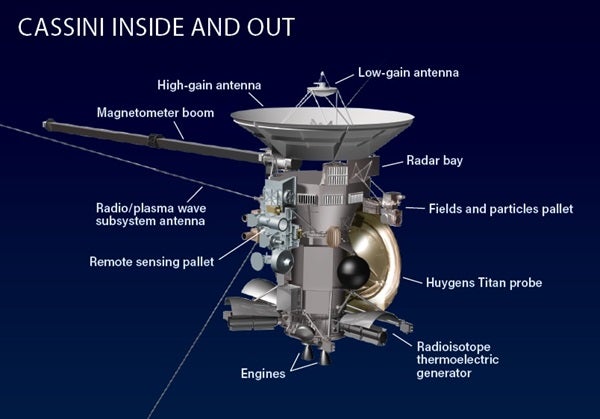

That all changed one year later, when Cassini’s magnetometer (think: fancy compass) detected something strange in Saturn’s magnetic field near Enceladus. This suggested the moon was active. Subsequent passes by Enceladus revealed four massive fissures — dubbed “tiger stripes” — in a hot spot centered on the south pole. And emanating from those cracks was a massive plume of water vapor and ice grains. Enceladus lost its label of being a dead relic of a bygone era and leaped to center stage as a dynamic world with a subsurface ocean.

Possible energy sources

One of the greatest legacies of the Cassini mission is that it established Enceladus as possessing all three ingredients for life as we know it: water, chemistry, and energy. Water in the ocean — check. Chemistry in the simple and complex organics detected in the plume — check. These could be utilized to form the molecular machinery of life.

Energy takes a bit more explaining.

It is likely that hydrothermal vents are present at the seafloor of Enceladus. We know this because of three lines of evidence. First, INMS detected methane in the plume, at higher concentrations than would exist if sourced from clathrates (water-ice cages at high pressure with methane trapped inside) or other reservoirs in the ice. Methane is a key product of hydrothermal systems.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Second, CDA discovered silica nanograins of a particular size and oxidation state traced to the ocean. These only could have formed where liquid water is touching rock at temperatures of at least 194 degrees Fahrenheit (90 degrees Celsius), in the range of hydrothermal vents like “white smokers” here on Earth.

And third, the recent confirmation of molecular hydrogen in the plume by the INMS team strongly suggests interaction of liquid water with a rocky core.

On Earth, hydrothermal vents at the base of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge host teeming ecosystems, living as far removed as one can imagine from photosynthesis. These habitats survive off of geothermal and chemical energy. A similar community might exist near a hydrothermal vent at the seafloor of Enceladus.

So, we have water, chemistry, and energy. Let’s say they have mixed together long enough for life to form. (Your guess is as good as anybody’s here — estimates range from 100,000 to 25 million years.) How might we detect it?

Assuming an energy-limited scenario (a good analog is Lake Vostok, a body of water in Antarctica that’s been covered with ice for the last 35 million years), we are probably looking at cell densities in the range of 100–1,000 cells per milliliter of ocean water. For reference, Earth’s oceans have about 1 million cells or more per milliliter.

We assume this life would use readily available building blocks — such as amino acids, which are abundant in carbonaceous chondrites and likely present all over the saturnian system — in numbers on par with Earth-based life.

This assumption is reasonable because life needs chemical complexity to carry out the reactions that keep cells functional. Then we are looking at concentrations of biomarkers on the order of less than 1 part per billion. That’s tough for current instruments to achieve, without some kind of concentration step.

Does this mean we have to wait for more advanced instruments before we search for life? Nope.

Of all the ice grains detected by the CDA instrument, a fraction had a high concentration of organic molecules, something the CDA team calls high mass organic cations (HMOC). While the instrument couldn’t specifically identify the structures of the HMOCs, a thorough analysis led to some educated guesses, such as aromatics (carbon-containing ringed structures) and oxygen- and nitrogen-bearing species. Within Enceladus’ ocean, there may be a complex organic soup of molecules.

The best theory for how these organic-rich ice grains might form is due to something called “bubbles bursting.” The grains were not only organic-rich, but also salt-poor, suggesting they came from an organic layer at the ice-ocean interface.

On Earth we have something similar floating at the surface of our ocean. It’s a film called an “organic microlayer,” as it’s not very thick and is typically made up of organics from biological activity (i.e., bits of cells) and from other sources, too.

The organic molecules like to hang out together and aren’t huge fans of salts or water, so they push these things out of the microlayer. Then, wave activity causes bubbles in this microlayer to burst, generating aerosols that are organic-rich and salt-poor.

A similar process may be happening on Enceladus. Organic molecules in the ocean may be concentrated at the ocean-ice boundary, and, just like on Earth, may force out the water and salts from this film. As the liquid surface at the base of the plume boils into vacuum, bubbles might burst and disperse the organic film, producing some grains that have a lot of organics inside, and little salt.

The result of all of this? Enceladus may be helping to concentrate the very things astrobiologists want to study the most: organic molecules.

Aerosols on Earth boast organic molecules enriched hundreds to thousands of times over typical ocean concentrations. If we collect samples by flying through the plume or by landing on the surface, we may have a greater chance of detecting evidence of life on Enceladus, if it exists.

Enceladus has captivated us and given us more than enough reasons to go back. Many possible missions would do the job, and a few have been proposed in the post-Cassini era, although not yet selected by NASA to proceed.

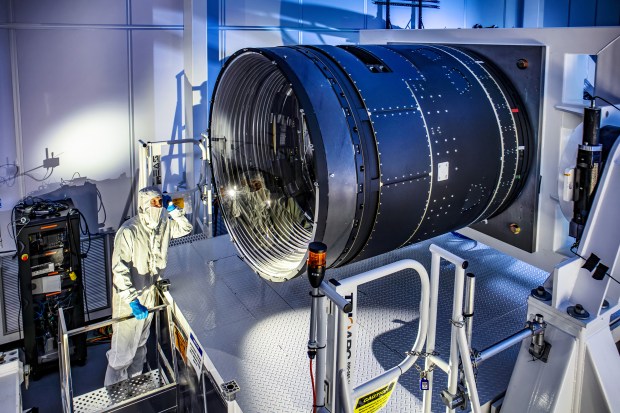

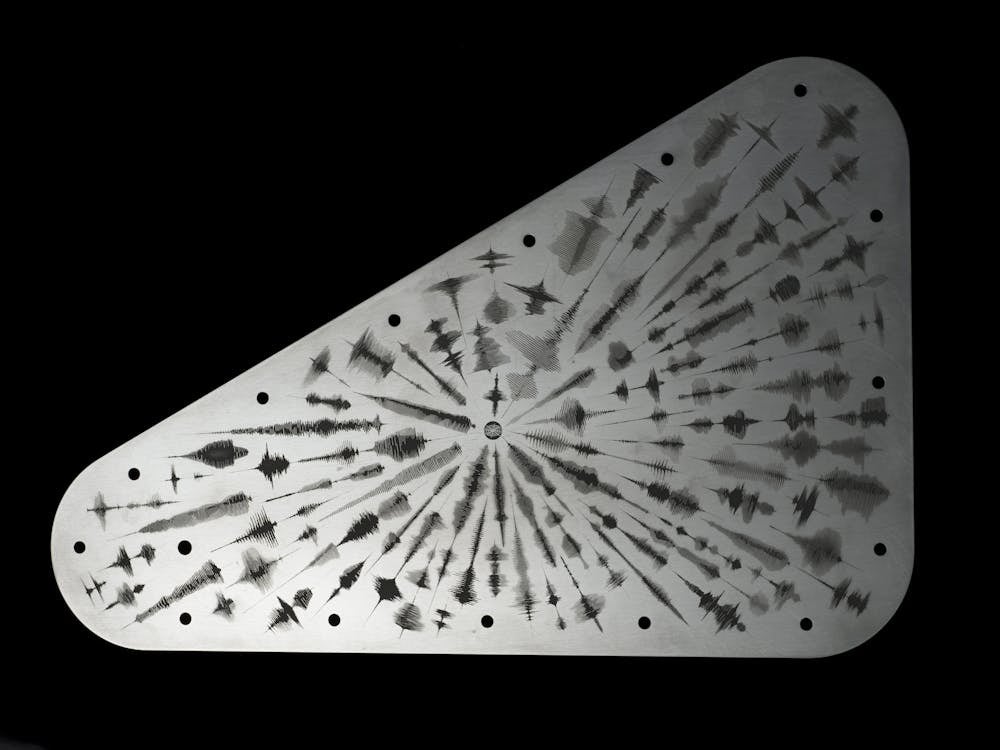

Some would do as Cassini did — fly through the plume and analyze the gas and grains — but with upgraded instruments capable of much more sensitive and effective tests for life. Others would land on Enceladus’ south polar terrain, sampling fresh snow deposited onto the surface from the plume.

Even more ambitious concepts include a sample return mission (although with a round-trip time of 14 years, we would have to wait awhile to get that sample) or various climbing or melting robots to descend the 1.2 to 6.2 miles (2 to 10 km) through the ice shell and reach the ocean itself.

Whatever we send, the next mission to Enceladus — if indeed astrobiology is its main objective — will need a well-designed suite of instruments capable of searching for multiple, independent lines of evidence for life. Our understanding of life’s characteristics has advanced greatly since the Viking era, the last time NASA openly stated the search for life as the primary goal.

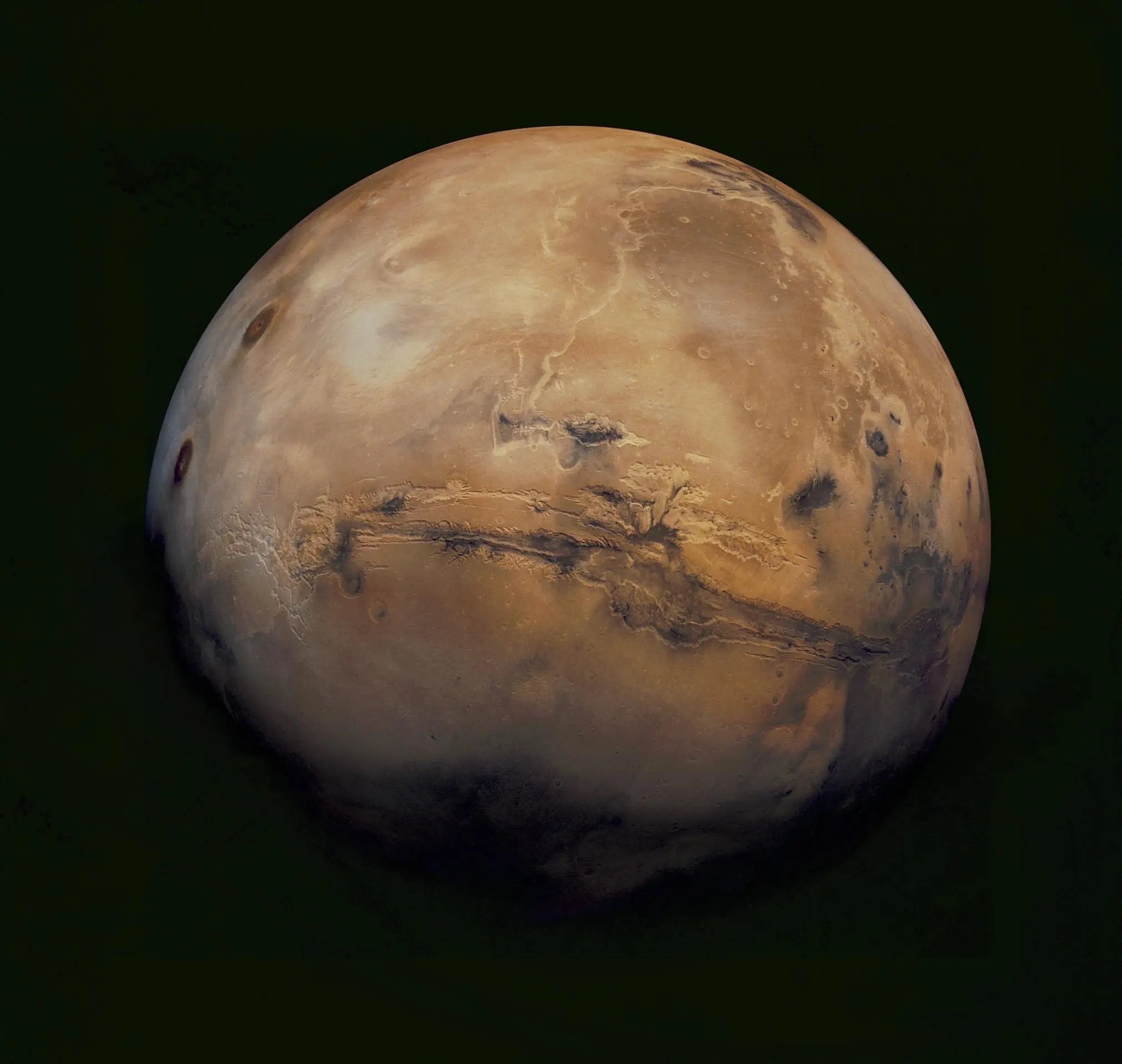

Back when the two Viking landers touched down on Mars in 1976, for example, we knew only two of the three branches of life. (Archaea, the third and most primitive branch of the tree of life, was discovered in 1977.) The Viking landers had three biological experiments designed to search for life in the martian regolith. One test result was positive, one was negative, and one was ambiguous. Since then, we have learned a great deal about how to design experiments such that an ambiguous result is much less likely.

We are also getting better at searching for biosignatures that are as agnostic to Earth life as possible. For example, a future mission to Enceladus might not target DNA, which is Earth-life-specific, but it might look for a molecule that could serve the same function for alien life: a large molecule with repeating subunits (akin to an alphabet) capable of storing information, such as the blueprints to build an alien cell. If such a molecule is detected, along with positive identification of multiple other biosignatures, a strong case could be made for the first detection in human history of life on another world.

Active, accessible, and relevant

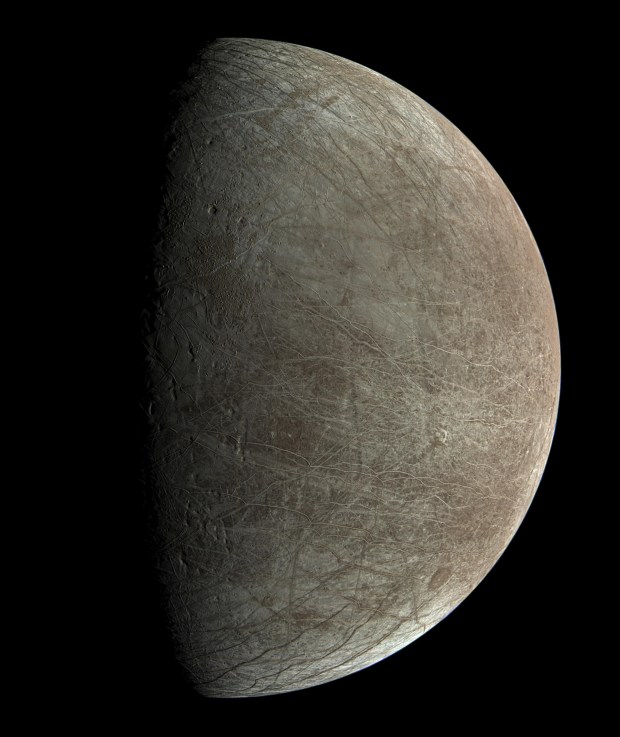

Enceladus is not the only place that could host life. Europa has an even larger liquid water reservoir, and Titan’s ocean may entertain an unimaginably rich organic chemistry.

But Enceladus is the one place where researchers know for certain that they can access material from the ocean without the need to dig or drill (or even land). We can use technology available right now to test the hypothesis of whether life may be present somewhere else in the solar system.

Enceladus may be a tiny moon, but good things often come in small packages. The time is now to answer the key question that has driven us since we first looked up: Are we alone?