Within Frombork’s massive walls, the astronomer settled down to write his treatise describing a heliocentric (Sun-centered) cosmos, eventually published as De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) in 1543. To this day, the great thinker rests just beneath the cathedral floor.

How should we think of Copernicus’ legacy, 476 years after his death? In some ways, he was a radical: His theory forced us to think of Earth as a ball of rock whizzing through space — a shocking idea at the time. But in other ways, he was conservative, imagining the planets moving in perfectly circular orbits, just as the ancient Greeks had believed some 14 centuries earlier. In fact, On the Revolutions was, in some respects, a “tweaking” of the Almagest, the book-length treatise on the structure of the cosmos written by the Greek thinker Ptolemy in the second century.

We also perhaps think of Copernicus too narrowly. His astronomical work certainly dominated the final decades of his life, so we remember him as an astronomer and mathematician. But he was also a churchman, a doctor, and an economic theorist.

A national treasure

The man who put the Sun in the center of the cosmos was born Niklas Koppernigk; “Copernicus” is the Latinized version of his name. Though his first language was German, he was a subject of the king of Poland. And today, Poland understandably celebrates him as one of its own.

In fact, every large city in Poland seems to claim some connection to Copernicus, and statues and memorials abound. In the depths of the Wieliczka salt mine, I came across a salt sculpture of the astronomer. I rode from Toruń to Kraków aboard the Kopernik train, and his name was the Wi-Fi password at one of my hotels. In the capital, Warsaw, an enormous statue of the astronomer stands in the city center while a science center — which includes a planetarium called the Centrum Nauki Kopernik — is just a few blocks east, overlooking the Vistula River. He is everywhere.

A visitor to Poland keen on walking in Copernicus’ footsteps might start in Toruń, the city of his birth, some 60 miles (96 kilometers) northwest of Warsaw. The house on Kopernika Street where he is said to have been born — a Gothic, red-brick building with an ornate façade and steep gables — is now a museum, called the Muzeum Dom Mikołaja Kopernika, or Nicolas Copernicus House Museum. The exhibits showcase Copernicus’ life and times, though the director told me Copernicus’ family owned more than one house, so there is no way to be sure the astronomer was born within these particular walls. (We do know that Copernicus’ family owned the house, beginning in 1463.)

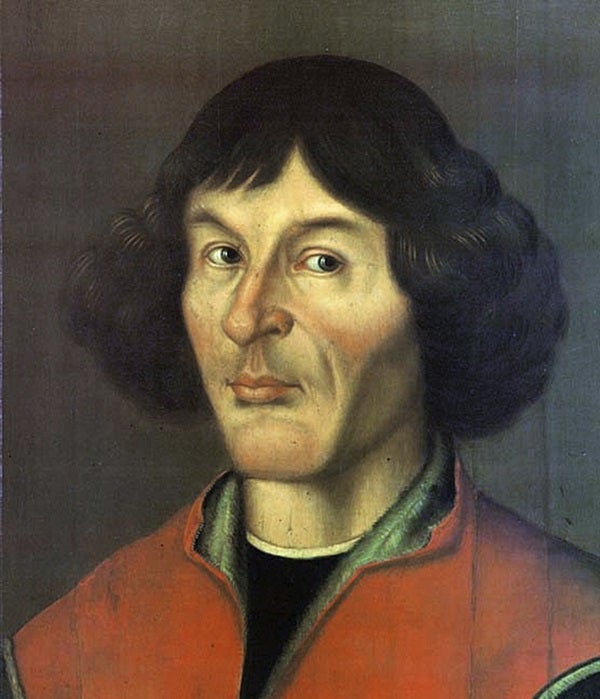

Also worth checking out is the museum in Toruń’s old city hall. Here, you will find the most famous portrait of the astronomer: the oft-reproduced painting in which the young Copernicus sports a red jerkin and jet-black hair in a surprisingly modern cut. I expected the painting to dominate whichever room it was in, but it is just the opposite — it is fairly small and hangs alongside a dozen or so portraits of historic figures in a grand hall on the second floor. More selfie-worthy is the enormous bronze statue of Copernicus on the street beside the southeast corner of the building.

Copernicus was born in 1473, the son of a wealthy merchant. He studied first at the University of Kraków and later in Italy at Bologna, where he focused on canon law (laws governing the rights and responsibilities of church leaders). He later earned a medical degree at Padua, near Venice.

Copernicus’ uncle, a powerful bishop, supported his education and travels after his father died in 1484. In 1497, he settled in Frombork (known as Frauenburg in Copernicus’ time) in the province of Warmia, on the Baltic Sea. There, his uncle appointed him as a canon, a position just below that of priest. After returning from Italy with his medical degree in 1510, he remained in Poland for the rest of his life.

Copernicus lived comfortably in Frombork with taxes collected from the region’s tenant farmers, as well as a second income from the cathedral. His medical and administrative duties kept him busy. We know he tended to his uncle’s medical ailments, which apparently he complained about fairly frequently. He also wrote on economics, studied the problem of counterfeiting, and made recommendations on currency reform. Yet his mind was clearly focused on celestial matters. While still a student, he had taken great interest in the Moon’s occultation of the star Aldebaran in 1497 and a lunar eclipse in 1500.

As his contemporary Laurentius Corvinus noted, Copernicus could discuss “the swift course of the Moon and the alternating movements of his brother [the Sun] as well as the stars together with the wandering planets — the Almighty’s marvelous creation — and he knows how to seek out the hidden causes of phenomena by the aid of wonderful principles.”

The Gothic cathedral complex where Copernicus did so much of his work still looms over Frombork. Its imposing turrets and fortifications rest on foundations dating to the 14th century. Today, visitors enter via a footbridge that crosses a dry moat, leading to the massive main gate. The Bishop’s Palace at the east end of the complex is now a museum displaying artifacts relating to Copernicus’ work, including an early edition of On the Revolutions and samples of his writings on other subjects, such as economics and cartography — a reminder of his wide-ranging interests.

Copernicus’ personality is harder to discern after four centuries, but in documents from that time, a generous streak is apparent, says Dava Sobel, author of A More Perfect Heaven: How Copernicus Revolutionized the Cosmos. “When he went to collect the rents from the tenant farmers, he treated them fairly,” she says. “If they were elderly, he lowered the rent. Or if they didn’t have children to help them on the farm, he would do something to help them out, like giving them a horse. . . . So it seems to me like he was a remarkably decent person.”

Changing the heavens

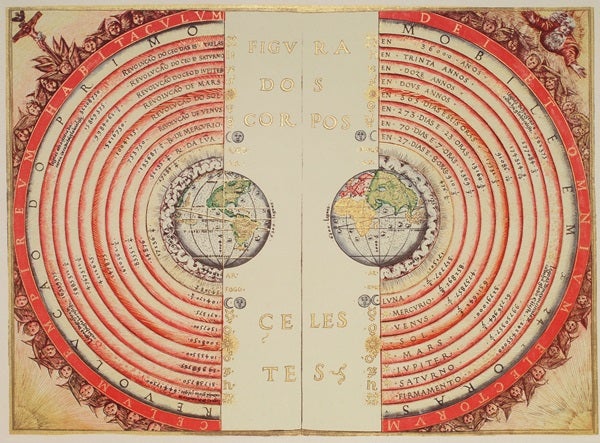

Though Copernicus would reimagine the structure of the heavens, the old geocentric (Earth-centered) system of Ptolemy was adequate for predicting planetary motion. Its picture of a stationary Earth, with the heavens whirling around, meshed with everyday experience.

Yet something troubled Copernicus. For Greek thinkers like Plato, the circle was the ideal geometrical form. Planets, in the heavens, must surely move in perfect circles — an idea that Copernicus seemed to endorse. But he also believed each planet should move at a constant speed along those circles. In Ptolemy’s system, the planets moved at a constant speed only relative to an imaginary point: the equant. To Copernicus, this seemingly arbitrary construction was at odds with the spirit of Plato’s vision.

What would happen, Copernicus wondered, if the Sun, rather than Earth, lay at the center of the observed motions? Perhaps now the planets might move along circular orbits at constant speeds, and still account for what was observed in the sky. (He was half-right; the planets do revolve around the Sun, but their orbits are elliptical, and they speed up and slow down as they orbit, as German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler would eventually show.)

“Those two diagrams have a lot in common, including the order of the planets — except that the Sun and Earth have swapped places,” says Dennis Danielson, a historian of astronomy and a professor of English at the University of British Columbia. Danielson points out that the “calculating power” of the models — the ease of actually figuring out when a planet would be in a certain position — was about the same in the two models.

Copernicus was likely driven by a sense of aesthetics, Danielson says. “This is a beautiful arrangement,” he says of Copernicus’ model, “because with the Sun in the center, the periods of the planets are now monotonic.” That is, the period of each planet’s orbit gets progressively longer as one proceeds outward, away from the Sun. Once Copernicus had made the switch, he became enamored with it. He wrote of the “marvelous symmetry of the universe” afforded by his system. As he put it in On the Revolutions: “Truly indeed does the Sun, as if seated upon a royal throne, govern his family of planets as they circle about him.” There was no going back.

Among his concerns: The heliocentric model appeared to challenge what the Bible said about the workings of the cosmos. (A passage in the Book of Joshua, for example, seems to describe the Sun moving around Earth.) Copernicus wanted no part of such controversies and successfully avoided conflict; Galileo, in the next century, would not be so lucky. The Italian thinker famously provoked the ire of the Roman Catholic Church over his endorsement of the Copernican view by saying the Bible was open to interpretation and needn’t conflict with what science had revealed about the heavens. That irked Church authorities, who felt he was encroaching on their intellectual turf. Galileo was tried for heresy and placed under house arrest. Some of his writings, along with Copernicus’ book, were banned.

Copernicus fared much better, never suffering directly for his beliefs. Nonetheless, he waited decades before allowing his work to be published. In fact, On the Revolutions might never have seen the light of day, had not a young German mathematician and clergyman, Georg Joachim Rheticus, paid a visit to Copernicus in Frombork in 1539. Rheticus encouraged Copernicus to complete his manuscript and oversaw its publication. The encounter and subsequent friendship between Rheticus and Copernicus forms the heart of Sobel’s stage play, And the Sun Stood Still.

When On the Revolutions was eventually published in 1543, it contained a preface added by a Lutheran clergyman named Andreas Osiander. The preface urged readers to treat the idea of a Sun-centered system as a mathematical convenience rather than a literal description of the cosmos. We know that Copernicus never intended such a disclaimer because a surviving manuscript of the book, written in Copernicus’ own hand, contains a very different preface, explains Jacek Partyka, a classics scholar and translator at the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków. (That manuscript is the library’s most prized possession.) Partyka points out that even the title of the book was altered for publication, adding the phrase orbium coelestium, or “heavenly spheres,” thus putting the emphasis on the heavens rather than Earth and avoiding the vexing issue of Earth’s motion.

The idea that our world was a planet hurtling through space was still controversial, Partyka says: “To most philosophers or scientists at that time, it would have been unthinkable.” According to legend, Copernicus was presented with a copy of the published book as he lay on his deathbed; he is believed to have died of a stroke soon afterward. Partyka is only half-joking when he suggests that seeing the changes to the book might have been the last straw. “If I was Copernicus, and I had seen this, I probably would have had a stroke, too,” he says.

500 years later

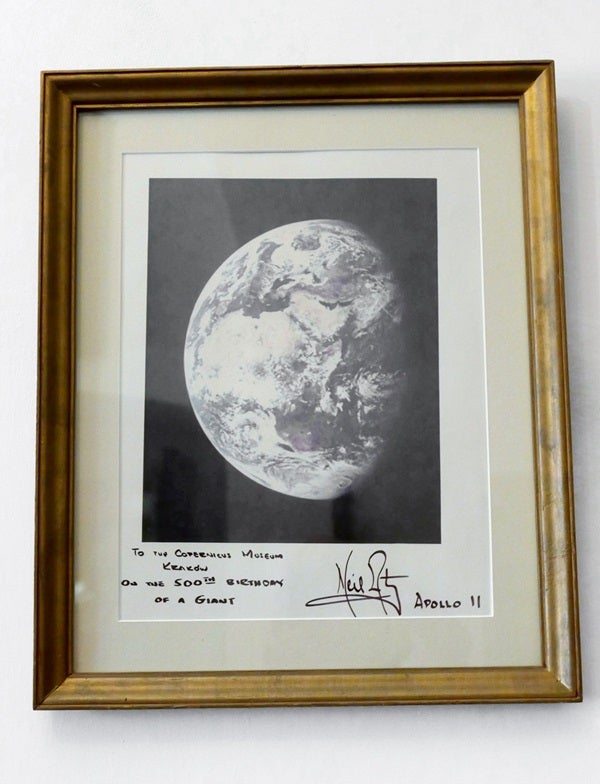

In Kraków, the most important Copernican site is the Collegium Maius. Dating to the 15th century, it is the oldest surviving university building in Poland. Among the college’s voluminous exhibits are astronomical instruments from Copernicus’ time, an assortment of astronomical texts and manuscripts, and — a more recent acquisition — a signed photograph of Earth taken by Neil Armstrong during the Apollo 11 mission and donated to the college in 1973 to mark Copernicus’ 500th birthday.

A lasting legacy

Even in death, Copernicus continued to provoke controversy. For one thing, no one was quite sure where his remains were. In 2005, archaeologists found what they believed to be his bones beneath the Frombork cathedral’s floor. Experts concluded the skull was that of a man who had died at age 70 — Copernicus’ age at the time of his death — and that the facial features matched known portraits of the astronomer. DNA from the bones matched traces found on a book he owned as well. In the spring of 2010, Copernicus was given a second funeral, and his remains were buried in Frombork Cathedral, in the same spot where his bones had been found. His casket can be glimpsed beneath the floor, through a small glass panel.

After photographing the great thinker’s tomb from every conceivable angle, I left the dark nave of Frombork Cathedral and emerged into the late summer sunshine. As I gazed up at the sky, I was struck by the magnitude of what Copernicus had achieved. Earth feels perfectly still beneath our feet; to see that it is not so requires an extraordinary leap of the imagination. I was left with a feeling of awe at this larger — and all the more amazing — universe that he gave us.