He is often called the “third man” of the most historic Moon mission ever. Michael Collins did not walk on the Moon; instead, he orbited the lunar surface during that first Moon landing, keeping vigil over Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as they walked the surface below. But Collins has no sense of being an outsider when it comes to Apollo 11.

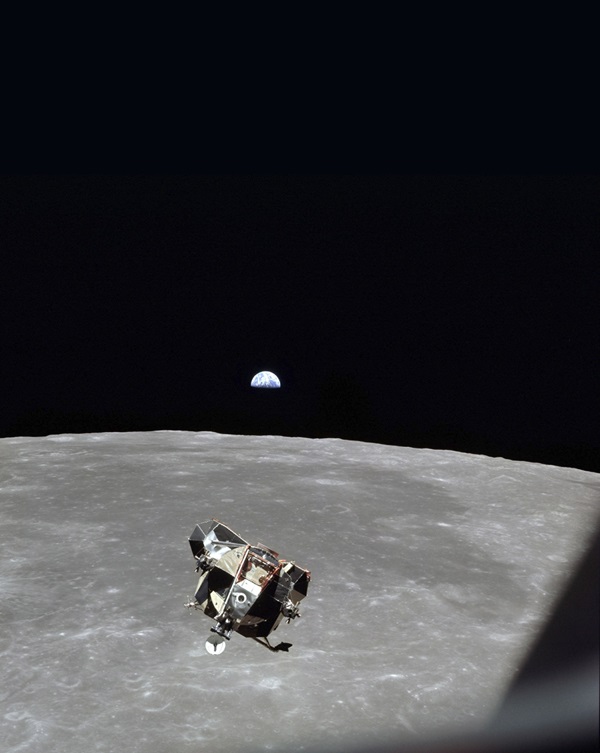

His task was so critical to the mission, and he was so close to his comrades, that Collins felt no loneliness as he orbited the Moon. He looked down toward Tranquillity Base and also back toward the small Earth. Yet isolation was not in mind. During that incredible time, as the world watched and waited, Collins kept the operations in the command module sharply moving, making a successful Moon landing — and return — possible.

The product of an Army family, Collins was born in Rome, and was educated in Washington, D.C., and then at West Point, before joining the Air Force. His father was a U.S. Army major general, and his uncle was J. Lawton Collins, chief of staff of the U.S. Army.

Collins’ service included periods as a fighter pilot and as a test pilot before joining NASA’s third astronaut group in 1963. This set him on course to become part of the most celebrated group of astronauts ever, the Apollo 11 crew: Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins.

Recently I had the chance to speak at length with Collins. At 88, he is still sharp and entertaining to talk with. I hope you enjoy the results of our discussion.

Collins: I grew up in a military family. My brother, my father, my uncle were all in the Army. When I finished West Point, for nepotism or whatever reasons, I sort of slipped off into the Air Force and entered pilot training. I started in Columbus, Mississippi, for primary training in the T-6, the venerable old T-6. It was a wonderful experience for six months learning to fly a little bit, and then I moved on to Waco, Texas, for jet and instrument training and got my wings and so on.

I was trained in F-86 Sabre jets, which at that time were fighting the MiGs in Korea, and I had orders to go do that. But the armistice was signed and those orders were canceled, and poor me, I had to go [to] Southern California, which is quite a hardship, and after that to France where I was in a fighter squadron there for a couple of years.

Then I went out to Edwards, which was really our mecca, and entered the Air Force Test Pilot School and later a post-grad version of it which they gave a grandiose name. Instead of the Test Pilot School, it was called the Aerospace Research Pilot School, and that sort of completed my education. I joined people like Frank Borman.

Astronomy: Your father was Maj. Gen. James Lawton Collins, an important Army veteran of both World War I and II. Did his background and your upbringing in a military family influence your desire for exploration?

Collins: I did have a strong Army background. At that time, my father, who was a major general, as you say, and had various assignments in World [War] I and II, and my brother at that time was a colonel in the Army, and later went on to become a brigadier general, but the main force there was my father’s younger brother who was the Army chief of staff at that time. He was J. Lawton Collins, nickname was Lightning Joe, and he was given that nickname because he had led an Army division from Normandy across France and into Germany at a very rapid speed during World War II.

Astronomy: Moving on a couple of years later, in 1966 you were the pilot for Gemini X and went into space along with John Young. This was a complex rendezvous docking and extravehicular activity (EVA) mission. Can you describe the flight and your recollections of it?

Collins: I really loved Gemini. It was kind of like a neat little flying motor scooter. It was called the Gemini Program, named after the Gemini Twins because it carried two people. I thought — well, Janus, I guess, was the god of doorways, and I thought Gemini should more probably have been called Project Janus because like that god, it looked backwards and it looked forwards. It was backward to the Mercury Program and it looked forward to flying to the Moon on Apollo, and its job was to link those two, to take the experiences of Mercury and to concentrate on three areas. The first one was bringing two vehicles together in space, rendezvous and docking them, and then the next was to be able to go out onto the surface of the Moon and therefore these were our first ventures outside a spacecraft to do spacewalks.

Astronomy: In order to achieve your rendezvous with an Agena target vehicle, you orbited a then-greatest distance from Earth, some 474 miles (763 kilometers) above Earth’s surface. What was that sensation like, when you were in what then was considered to be deep space?

Collins: Well, [474 miles] was, as you say, a world record at that time, and as a former test pilot we always loved to set records, so John and I were happy to be able to do a new altitude record on Gemini X. But in terms of anything [happening] on board, it was nothing. Once you get above 100 miles or so it doesn’t matter really whether you’re 200, 300, 400, or 500. The view out the window changes imperceptibly as you go up, but those were just little numbers on our instrumentation rather than any sensation.

Collins: The spacewalking, EVAs as we called them, that was the part I suppose I remember most vividly about the flight of Gemini X. We had our own Agena, which we had docked with. It was our motor. So we used that motor to get us up to the orbit of where a dead Agena was awaiting us, an Agena without any power, and then John’s job was to maneuver the Gemini very close to the Gemini VIII Agena. That was a difficult task.

And then I got all prepared with my EVA gear. We dumped the cabin pressure in the Gemini, opened the hatch, and I floated out. So, the first time that I approached the Agena, I guess we were maybe 20 feet away from it, slightly below it, and so I just sort of gently pushed out and I went over and hit the Agena down at one end of it. The experiment package that I was to receive was, I guess, maybe 10, 15 feet up the side of the Agena, and as I was going toward it, there were no manufactured handholds or anything for me to grab a hold of.

So I was sort of slithering along the side of it, and when I got to the experiment package, I had enough momentum in my body that I couldn’t stop there. I reached down and grabbed the package with one hand, but I just slid right on by it, and then I went sort of spinning past and above it out to the end of my umbilical, which was a big, long 50 feet. I was way above and past the Agena, and as I swung around, I could look down and, of course, see both of them, but I couldn’t do much about it. So, with the umbilical fully extended, I then entered a gentle arc and I swung around and came back and I got my legs back inside the open Gemini cockpit. And then John maneuvered again and got back where he had been before, maybe 20 feet away [from the Agena].

This time when I left the cockpit I had a little handheld maneuvering gun that just squirted gas out. I stubbed my toe a little bit as I left the cockpit, and I started pitching a little bit. I used the gun to correct that, but in the process that lifted me up a little bit higher. So, as I got over to the Agena, I almost missed it. I had to stick my hand down quickly and I grabbed some wires that were not supposed to be grabbed, I suppose. With my left hand holding firmly, I kind of swung around, and this time when I went back to the instrument package I was more careful about my body momentum. The package released very easily and then I made a return trip.

So I just had to get back inside a small space with the trailing umbilical cord, 50 feet long and very thick, because it contained oxygen. [It was] a strong, ropelike thing so it wouldn’t break, and so it was like — I think I told the ground it was something like a snake at the zoo or something. I had this thing that I had to get under control. We finally stuffed it in below my feet under the instrument panel.

Collins: Not that early, no. They were kind of strange animals to us, and we were kind of strange to them. Vodka helped.

Astronomy: [Laughs]

Collins: We did meet [Konstantin] Feoktistov, the one that I remember, and I guess the other one was . . .

Astronomy: Pavel Belyayev.

Collins: Yeah. Anyway, the two of them. We escaped the crowd, if I remember. They were badgering us, so we escaped into a transport, which I believe was one of those Russian transports that brought them there, and for, I don’t know, an hour or so we sat around and drank vodka and chatted. I liked them, and we were kindred spirits. We clearly were from opposite poles when it came to political opinions, and we didn’t get into that. We talked about — I’m sorry to say it’s so long ago I don’t remember the details, but we talked about flying stuff, you know?

Astronomy: Such as?

Collins: Airplanes and spacecraft, and they seemed very friendly. We were friendly to them, and their backgrounds and their careers dovetailed with ours in many ways, so we were a compatible group. But we had no expectation going into that that we would have a meeting like that with the cosmonauts. We hadn’t been briefed by the State Department or NASA or the government — “Oh, yeah, be careful of this, or do say that, or don’t say the other” — it was just all spontaneous and very informal, and I think useful in a minor way in the long run.

Astronomy: Gemini having served as a test bed for Apollo, you originally had a different assignment, of course, than Apollo 11, but the assignments were shuffled. You also had some medical issues that delayed your involvement. What was it like, sort of playing that waiting game as the missions unfolded in the early days of Apollo planning?

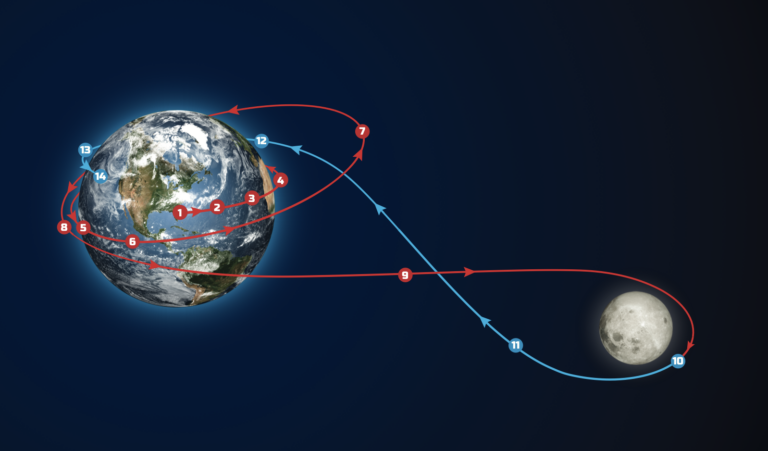

Collins: Like you say, I was on the first Apollo crew with Frank Borman and Jim Lovell, and I was removed from that crew because I had two vertebrae in my upper spine with problems. One of them had come loose, and I had to have those two vertebrae fused together. So for about six months, I was not allowed to fly airplanes because my spine hadn’t fully healed and also I couldn’t really keep up with the training regimen that was required of the crew. So I was removed, and my job then became the guy in Mission Control who talked to them on the radio. That flight, when I was assigned to it, was to be a very high orbit, but in the Earth’s orbit. I think we were supposed to go up — I don’t know precisely but, oh, 600 miles or maybe more than that — I’ve forgotten the numbers, but very high Earth orbit.

But at that time, I [think] NASA in its mission planning got a bit more venturesome. George Low, I think, was the primary man involved, but somewhere along the line, the hierarchy at NASA decided that the one and only predecessor Apollo flight, Apollo 7, had been a 13-day or so test in Earth orbit of the command module systems and that the LM was kind of lagging at that point. So it seemed like it was a good idea and a daring idea to take the command module, and instead of just flying into a high Earth orbit as we had planned — 1,000 miles maybe? — they decided to change that and fly all the way to the Moon. And of course that was Apollo 8, which we all remember because the crew read from the Bible in orbit around the Moon.

My part of it was, of course, minuscule, but there I am on the console in Mission Control and we’re about to have what I thought [was] the most momentous instance in exploratory, if not human history. Here people were exceeding escape velocity. They were leaving Earth’s gravity for the first time. They were going off to another planet for the first time. All these gigantic firsts and how would one listening know? Well, I said, “Hey, Apollo 8, you’re go for TLI [trans-lunar injection],” and Frank Borman said, “Roger.” That was it.

Astronomy: [Laughs]

Collins: I thought, you know, drums should’ve played, the pope should’ve sent a blessing, the president should’ve arrived, and any other embellishments you could possibly think of.

Astronomy: It was a moment for brevity then if nothing else.

Collins: Yes, and you know, we had a lifetime of radio discipline. You didn’t chatter on the radio.

Astronomy: What was it like when you realized that Apollo 11 — your flight now and you’re piloting the command module — would mark the first lunar landing mission?

Collins: I had been a little bit disappointed, oh, maybe a year or so before that, because when I was on the first [Apollo] crew, I [was supposed to] be the lunar module pilot. [But] then, because of my dropping out, the next time I was put on a flight I was put up into the command module pilot. I was bumped out of being a lunar module pilot because we had added Bill Anders, and the rule that Deke Slayton had at that time was that if you were going to be the command module pilot and be flying by yourself solo around the Moon, then he did not want a rookie to do that; you had to have flown once before. I had flown on Gemini [and] Anders had not, so I was bumped upstairs, and I became a command module pilot. And I knew then — that would’ve been in ’67, maybe — I knew from then on that I was not gonna walk [laughs] on the Moon.

So, I guess I’d say there was just a tiny little taste of disappointment with my role on Apollo 11. However, people point that out to me all the time, and I can say with great sincerity and honesty that I was just delighted to be on that flight in any capacity. I did not have the best seat of the three — I can see that — but the seat I had thrilled me. It was a culmination of John F. Kennedy’s dream, man on the Moon by the end of the decade, and to be any part of that historic flight suited me just fine.

Collins: Getting into the spacecraft is sort of odd. It’s not like you go out to that gigantic booster every day, but we’d been out there a number of times, and it was always a beehive of activity: The workmen doing this, that, and the other, big cranes going up and down. The day of launch — 16th of July, I guess it was, of ’69 — it was odd because it was quiet, it was silent, it was — something was wrong. There was nobody around. It was just us and one other guy.

And we got on this dinky little elevator and went up roughly 360 feet and got off at what they called the white room. It wasn’t white, but a little enclosure. And we got off there and then slowly one by one, other things happened.

We loaded ourselves into the command module, Columbia, but I had plenty of time to look around. I can remember if I closed my right eye, all I saw was the beach and the ocean and the world of Ponce de Leon, it could’ve been. There was no sign of humanity. It was just good Planet Earth. Vice versa, if I closed my left eye, then I saw this gigantic heap of complex machinery, the 20th century that we were, people of machines, and I can remember looking and saying, “Geez, I see that, I see that — I’m not sure if I’m in the right one.” [Laughter] But anyway, at that stage of the game, there wasn’t much I could do about that.

Collins: So little by little, we got loaded up. People always ask, “What seat was yours?” There were three couches actually, side by side. The one on the left was the commander and it wasn’t like Neil’s seat, Buzz’s seat, and my seat; it just depended on what was going on. For launch, I was over on the right-hand seat. When we got up into orbit and we wanted to retrieve the LM from its little hideaway top of the Saturn, then I went and got in the left seat. That was part of my job. And most of the time, I might be in the middle seat fooling with the computer. So, all three seats were mine in a sense.

Our departure from launch pad 39A was a little different than certainly what I expected. You know, the Saturn V is such a gigantic thing — I think 7.5 million pounds of thrust from the five engines — you would expect that inside there’d just be a deafening roar, but not so. It was a lot quieter than you might imagine. We could hear each other on the radio and hear each other and the radio by itself, and the acceleration was very slight. It leaves the pad extremely slowly.

The surprising thing is it has to keep itself poised because it’s only 2 feet away from the tower, and if it goes sideways a little bit too far, it bumps into the launch apparatus. Of course, that [would be] the end of it right there. So, to compensate, you have to, in our case, use those rocket engines as swivels, and so they were swiveling back and forth to keep us absolutely straight upright and not bumping into the launch tower. And the sensation that we felt, I always describe it as a nervous novice driver driving a wide car down a narrow alley; he or she will be jerking the wheel back and forth a little bit to keep you on track and not hitting the walls of the alley.

And we had the same problem; so we went with these little spasmodic jerks for the first while, and then once we cleared and that all settled down, the rocket ride is pretty smooth. I think the Gemini went up to about 7.5 gs at its peak. On Apollo it was like 4.5 gs. So, it was a relatively easy ride. When the first-stage engine quit, there’s an instant of noise and confusion — not so much noise, but visual confusion as you get separation. It’s almost like an explosion. The stuff out your window, you’re not sure what the hell is happening, but it’s fire and man-made particles and craft out there, and that lasts just a second or two. And then you’re past it, and you’re into the second-stage burn.

The second stage during its testing had not been quite up to snuff as compared to the first and the third. They’d had some problems with it, and we were, I think, probably worried about that second stage — not excessively — but it turned out to be smooth as glass. It was a beautiful ride, and then the third stage took over briefly to put us into orbit around the Earth. The third stage was not quite as smooth with little hiccups here and there, but it worked fine. The next thing we knew, we were in Earth orbit.

Astronomy: Much has been made, of course, of Armstrong and Aldrin descending in the LM and the first moonwalk. But this was a three-man mission, and your orbiting overhead obviously was critically important. You’ve said that you’ve never really felt lonely when you were in lunar orbit. How did you feel once you got to the Moon?

Collins: Oh yeah, lonely. I tend to forget the word lonely, but you bring it back to me. Well, OK, when I got back from the flight, we were subjected to a lot of press inquiries. And when they came to me, most of them centered on, “Weren’t you the loneliest man in the lonely history of space, behind the lonely Moon all by your lonely self?” And what I say in my book is, “Geez, what are they talking about? I’ve got white mice on my mind.” We are in a lockup there at Houston, hoping we hadn’t brought any alien pathogens back from the Moon. And we have this colony of white mice — whom I liked, I liked to interact with them — and so these guys are talking about —was I what? Lonely?

Astronomy: [Laughs]

Collins: I thought their question was ridiculous. I was tempted to laugh at them, the press, but ooh, that’s a mistake because they can retaliate. So I simply said that I was too busy to be lonely; however, the truth was considerably different.

I was very happy with the command module. In a way, I thought that it was like a little miniature cathedral. I had the transept, if you will, or the three couches, and then I went down this aisle into the altar area. The altar was really our guidance and navigation station, and we didn’t have any clerestory windows, but we had nice lighting inside, and it was an elegant, sturdy, spacious place. It was my home. I was king, and you know, like most kings I had to be careful. Like, there goes fuel cell No. 3 acting up again.

I can’t say that I really was relaxed, but I was happy to be there, [and] I felt very much a part of the mission. I felt like I was doing a useful job and I felt included, not excluded, and so I was king of my domain, and I was very happy to be there that way and lonely — no! Let’s talk about white mice. Geez.

Astronomy: Can you describe what was going through your mind, hearing about the descent of the LM, the landing, the EVAs conducted by your colleagues? That must have been a fairly exciting but also tense time to hope that everything unfolded as it should have.

Collins: I wasn’t too worried about the landing. I thought that it was — I don’t want to say a straightforward procedure, but it was one that had been practiced over and over again. I thought that Neil somehow would find a place to land, and it turned out it wasn’t our first choice, but he overflew several boulder fields over several crater areas. He finally found a place that suited him with about 30 seconds or so of gas left, and I thought he did a masterful job. I had expected that he would, and I’m glad that everything worked out. There was a radio delay and I couldn’t really tell what was going on, and it made me anxious for a few minutes there, but then when I was told that they were safely down I was, you know, not stressed.

My worry had been the rendezvous subsequent. You know, we’re in the space program, we’re big believers in redundancy, and we had redundant equipment wherever it was possible. It was not possible in the case of the Lunar Module Ascent Engine. It was one engine, one engine bell — I suppose multiple lines leading into it, but at one point — one incident of combustion where the engine lights or doesn’t light. If it doesn’t light, they’re dead men, and so I was very worried about that aspect, their getting off the Moon.

And then, once they got off the Moon, if they got into a perfect trajectory — which they didn’t do — then the rendezvous and docking was something we had practiced over and over and over again. However, if there were variations on the theme — what if things didn’t get out of control exactly, but they got crazy? I was in orbit, zooming by some 60 miles overhead, and if they timed it perfectly with my approach, and then they lifted off — OK. And they got into an orbit below me and then later transferred up to my orbit.

If they were late getting off, I couldn’t have slowed down for them, so they would have had to catch me quicker, and the way you catch someone quicker in orbit is to go lower. So maybe they’re a little bit late, so they go lower in their orbit.

If they are later yet, the orbit’s gotta be lowered until they are just skimming the mountaintops of the Moon. If you’re a second or two later than that, the whole system reverses itself. Instead of going low, they have to go as high as they can go and let me, if possible, dip down — or then I have to make an extra turn around the Moon and catch them instead of them catching me. This is from a procedural point of view [and] is a totally different situation, and it’s just one of many.

Suppose they veer left or right? Suppose the orbit they get into is too high or too slow or too fast or too something or other? I had around my neck a book, a big book — 8-by-10-inch loose-leaf notebook kind of a book — with 18 variations of the rendezvous and docking. Some of them we had practiced over and over. Some of the others were so obscure, we never even practiced them in the simulator, but they were mathematically possible, and they could’ve happened. That’s the kind of stuff that I was worried about then.

I’d been worried about that for, you know, months before, and so once they got into a good orbit, I breathed a big sigh of relief. Once we got docked back together, a second sigh of relief. Then our next big hurdle was just — again, we were relying on one engine, but that engine — or TEI as we called it, Trans-Earth Injection — that was our get-us-home-burner.

Collins: Well, no. He will laugh at me because of our idiotic simplicity, but it was nice. We had Hasselblads, and the experts said, “Well, on the timing, 1/250 of a second is what you want.” And so the [photos] we were taking were all at infinity or almost all without the windows, of course. So right away, you’ve got two-thirds of your camera settings decided for you. You’re shooting at 1/250 of a second, and you’re shooting at infinity. The only thing left is your f-stop. Well, it was always at 11 — not always, but you might dip down to f/8 or go all the way up to f/16, but not usually. You could take a baboon and teach him to do 1/250, f/11 at infinity, and he’d be as good a photographer as me any old day.

Astronomy: Now after your Apollo time, you had a distinguished career. You were a major general in the Air Force, assistant secretary of state for public affairs, director of the National Air and Space Museum, undersecretary at the Smithsonian Institution. Could you just talk a little bit about what life was like for you in all those incredibly active areas that you were in after your days as an astronaut?

Collins: I had decided that Apollo 11 would be my last flight, and the reasons for it were complex. They had to do with the timing. We had what I called a knit-two, purl-one rotation. After 11, I’d have skipped two, been on the backup crew as a commander and then, eventually down the road, it turns out I would’ve been Gene Cernan’s on 17 — but at that time, it had nothing to do with being the last flight. I think at that time, there was an 18 and a 19. It wasn’t that; it was simply that I saw myself living in motel rooms for the next three years, being separated from my family.

I felt that we’d done what Kennedy told us to do and then it was gonna be a bit anticlimactic after that. But again, it wasn’t any single thing. It was probably centered more on my family. I put all that together and mixed it up. I said, “Uh-uh, that’s enough.”

So then I left. I wanted a clean break from Apollo, from the space program, from NASA. Then came the Air and Space Museum, which was then just kind of developing on Independence Avenue. It was a wonderful transition, and lots of fun.

This story was originally published June 20, 2019