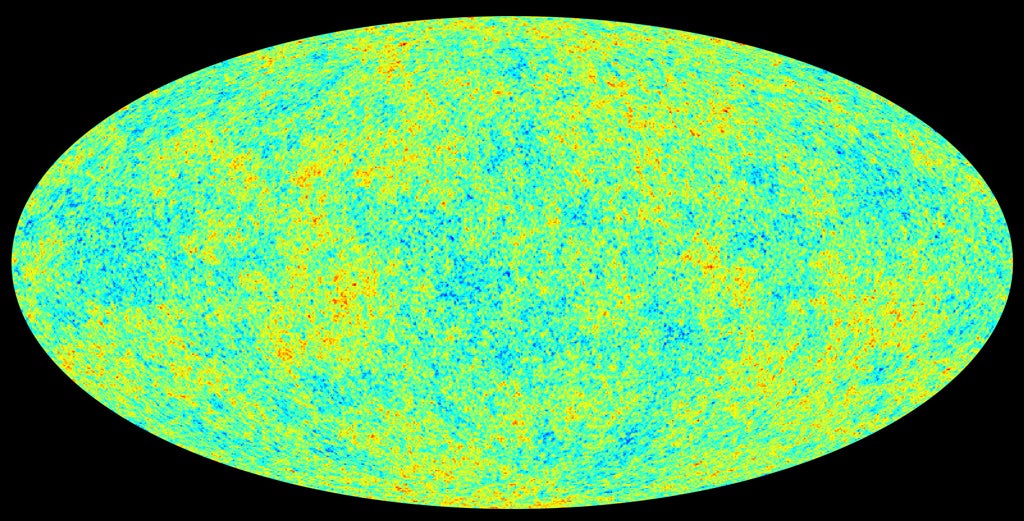

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) holds an immense amount of information about the universe’s properties. The key is to map this radiation in such a way to capture the smallest detail. Scientists have come a long way since first detecting the CMB in the mid-1960s. At the end of 2012, researchers with the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe released the mission’s final data, which shows the CMB’s variations smaller than 0.3° across and temperature differences of a few parts in 100,000.

So, how have CMB probes changed the appearance of sky maps changed since the first observation in 1965?