Being an observer is a quality you and I have in common. In the 21st century, it’s an attribute unusual enough to merit examination. That’s because modern humans tend to be busy and non-observational. This busyness means we are often scattered and unfocused.

In seeking examples of common activities in which one might naturally be an observer, motorcycling comes to mind. On my big old 800-pound (363 kilograms) touring bike, the word touring suggests I get to watch the changing scenery in a relaxed manner. But no such luck. A biker’s attention is typically split in multiple directions. You’re obsessively watching the road for ruts and gravel, while also focusing on the edge of the woods to spot any deer ready to spring out.

It’s not usually very relaxing. And neither is using a telescope, if we’re honest. If you have a restless mind — and most of us do, at least some of the time — your sky session brims with distractive choices. Should I change to a binoviewer? Phone a friend to join me? Insert a filter? Take some pictures? Boost the magnification? View something else?

In some states, teachers now give instruction in mindfulness. Children take to it readily and it converts restless, knee-shaking energy into a quiet, enjoyable focus on whatever is in front of them. For adults, meditation does the same thing. Calmly placing full attention on a single object, whether one’s breath or a candle’s flame, helps the mind perceive whatever’s happening with a pleasurable clarity that’s absent when attention darts between myriad things or mental chatter.

Observing — extensively watching an object — is a quiet activity with focused attention, a form of meditation. It is like nothing else. We observers are mindful without trying. By losing ourselves in the countless details of whatever’s in the eyepiece, we “grok” the celestial object with a satisfying completeness.

It’s said that backyard astronomers perform useful science and, while that’s sometimes true, it’s more often the case that the activity is as wonderfully purposeless as playing jazz. Or, if one must cite a goal, it’s simply to be amazed, or to have revelations.

For example, there’s a break in the lunar Apennine mountain chain, a gap equaling the distance between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore. It looks like a place where lava flowed. But which way? A careful look-see reveals wrinkle patterns that make it clear the magma went from Mare Serenitatis into Mare Imbrium, not the other way around. Good luck getting anyone else excited about this — but, for observers, seeing exactly what happened 3.8 billion years ago confers an oddly profound satisfaction.

Sometimes it’s not details that hold our focus. Sometimes the pleasure comes from observing something intensely alien. Who among us hasn’t deliberately looked at the 8th-magnitude star HDE 226868 in Cygnus solely because, once a week, this massive star is hurled around like a wrestler flung disrespectfully by its companion X-1, the sky’s surest black hole? There’s nothing visually special here. And yet we cannot resist.

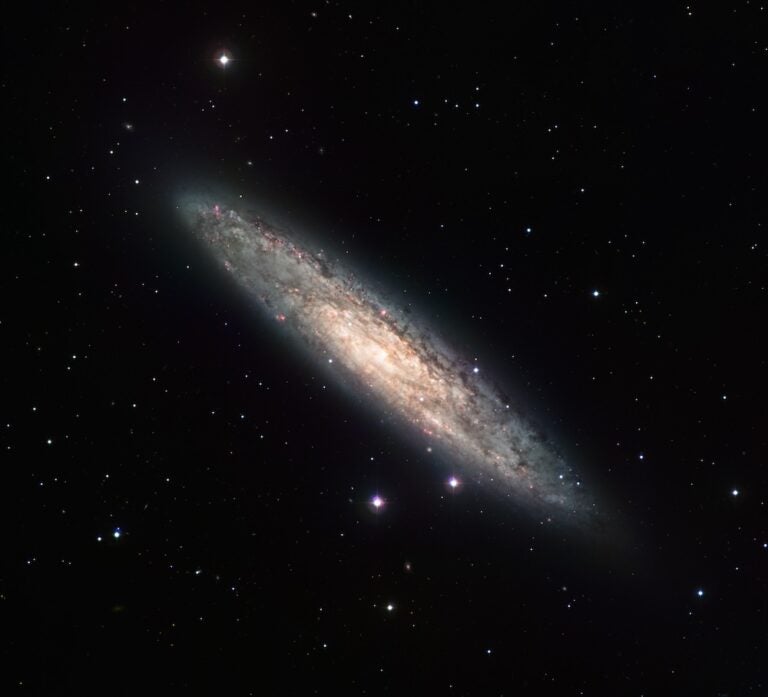

And who hasn’t taken the trouble to observe the violent version of West Side Story unfolding in Virgo? This is the strange, blue, near-lightspeed jet being hurled off the west side of the monster galaxy M87. Its color largely comes from Cherenkov radiation, emitted when electrons break the light-speed barrier. How can we not stare?

And how can I not feel a kinship with you, my fellow observers, at star parties and meets? Our bodies may be just as carbon-based as the other 8 billion members of Homo bewilderus. But we are not like them.