Key Takeaways:

- The recent discovery of pulsar J0737-3039 with a neutron-star companion in a close, fast binary system (2.4-hour orbit) offers renewed optimism for the direct detection of gravitational waves.

- This system exhibits a significantly faster orbital period than previously known gravitational wave-emitting binaries, such as the Hulse-Taylor pulsar (7.75 hours), which had led to a "bleak" outlook for detection.

- The challenging nature of discovering this faint, rapidly orbiting, and relatively short-lived system suggests that such tight neutron-star binaries are more prevalent in the Milky Way than earlier estimates indicated.

- This finding boosts the estimated neutron-star merger rate by a factor of six to seven, significantly enhancing the likelihood of observatories like LIGO detecting a strong gravitational wave event approximately every 1.5 years.

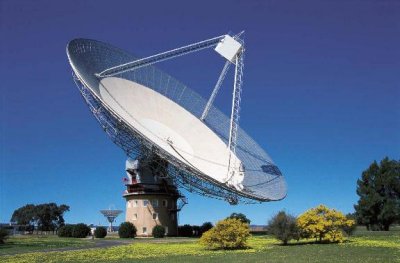

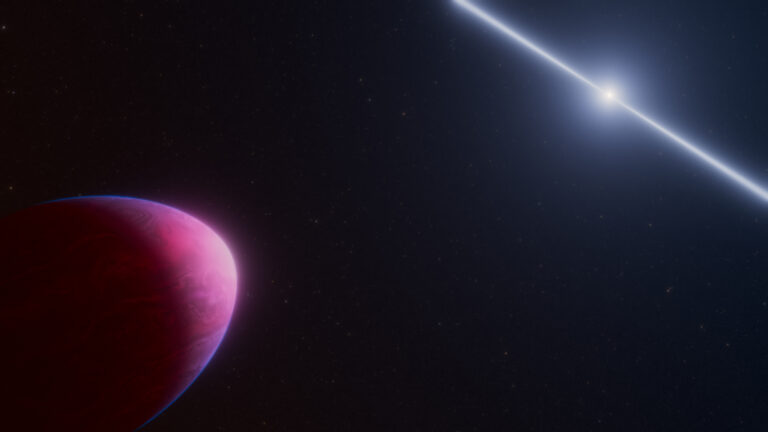

Compact objects like neutron-star binaries are just the kind of cosmic dancers capable of shaking up space-time. As they tauntingly spiral toward one another, neutron stars give off energy in the form of gravitational radiation. Recently discovered pulsar J0737-3039 and its neutron-star companion now are engaged in the closest, fastest tango of any neutron-star system ever observed, orbiting one another once every 2.4 hours. The pair was discovered by a team of scientists from Italy, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States using the 64-meter CSIRO Parkes radio telescope in eastern Australia.

Now, the prospect of detecting gravitational waves appears much more favorable. Because the newly discovered neutron stars are orbiting one another so quickly, the system’s life span will be significantly shorter than those of its two predecessors. These stars are expected to complete their dance eighty-five million years from now, when they will collide. Of course, that in itself is not entirely helpful, given that it is only in the last two or three minutes before they merge that they will produce gravity waves strong enough for LIGO to register. But the finding suggests that this type of tight, fast, and relatively short-lived system actually is common in our Milky Way — and much more common than binaries like the Hulse-Taylor.

In fact, the new data boosts the neutron-star merger rate by a factor of six or seven, which means LIGO should be able to detect such an event once every year and a half, a vast leap from previous estimates of only one every ten or twenty years. And if that’s the case, we won’t have long to wait to witness firsthand the extraordinary rolling landscape of Einstein’s universe.