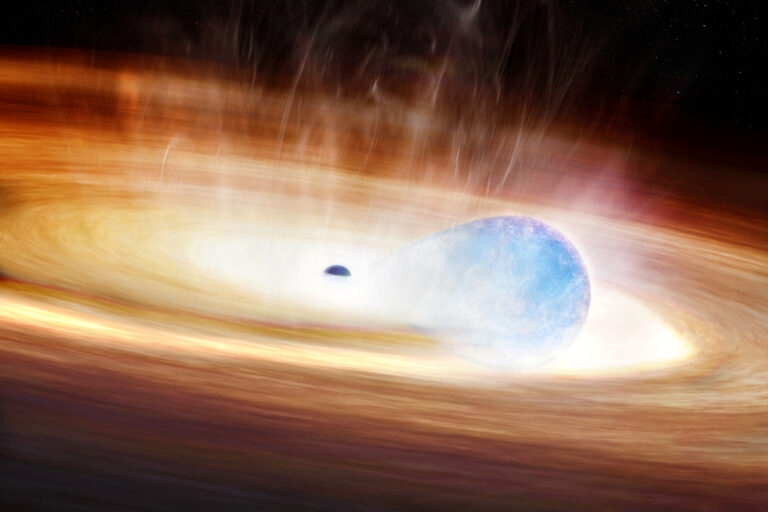

Massive stars have an outsized influence on their environment and the galaxies they call home. These behemoths have the highest surface temperatures of any normal stars, so they emit copious amounts of ultraviolet radiation that ionizes their surroundings. They also possess fierce stellar winds that help shape their gaseous environs. But these monster suns also burn through their nuclear fuels rapidly, so they don’t live long and thus are exceedingly rare.

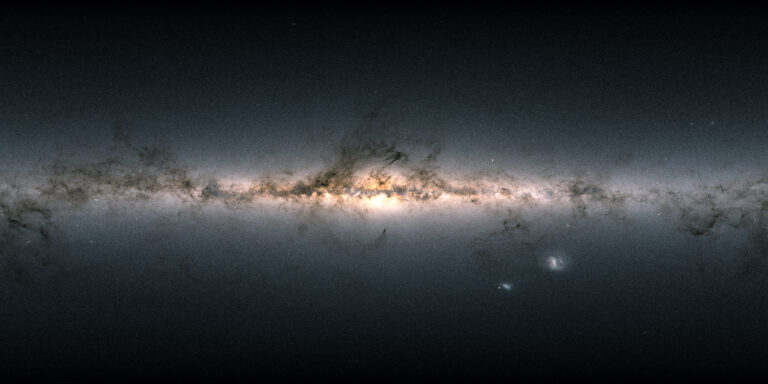

It’s no wonder astronomers were eager to turn the penetrating eye of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) on nearby regions of massive star formation. And what better place to target than the Sagittarius B2 (Sgr B2) molecular cloud? This giant region of cold gas and dust is the biggest and most active star-forming region in our galaxy. It resides a few hundred light-years from the supermassive black hole, dubbed Sagittarius A*, that lies at the Milky Way’s heart.

A Milky Way champion

At a distance of 27,000 light-years, Sgr B2 lies close enough to Earth that telescopes can provide a close-up view — only not at optical wavelengths. The dust that permeates the galaxy’s disk effectively blocks most of the visible light from this region, but the longer infrared wavelengths JWST observes pass through relatively unscathed. Recent images reveal many of Sgr B2’s massive young stars, the warm dust that surrounds them, and more than a dozen previously unseen regions of ionized hydrogen.

“Webb’s powerful infrared instruments provide detail we’ve never been able to see before,” said University of Florida astronomer Adam Ginsburg, principal investigator of the project, in a press release. “It will help us unravel mysteries of massive star formation and why Sagittarius B2 is so active.”

How active is it? The so-called Central Molecular Zone (CMZ) stretches more than 1,500 light-years across our galaxy’s core and holds approximately 80 percent of the Milky Way’s dense gas. Yet it produces only about 10 percent of the galaxy’s stars — less than one-tenth of what theory would suggest. Sgr B2 is the exception, creating nearly half of the CMZ’s stars in its 150-light-year-wide volume. It churns out stars at a rate of about 4 solar masses per century, which translates into eight to 10 stars. (No, our galaxy is not a prolific star producer.)

The new images offer a few clues as to why Sgr B2 stands out. First, the clouds that give birth to the most massive stars seem especially dense, which makes them more resistant to disruption. Second, a sharp boundary on the cloud’s eastern edge (visible at the top left of the images) hints that a recent event, perhaps the passage of a shockwave from a nearby supernova, triggered the recent bout of star formation.

Tip of the iceberg

The researchers say their results suggest that Sgr B2 may have only just begun creating stars. If so, the galaxy’s most active star-forming region has expanded its lead over second place. As lead author Nazar Budaiev of the University of Florida said, “For everything new Webb shows us, there are new mysteries to explore.”

Astronomers value every insight JWST delivers into massive star formation not only for what it reveals about the Milky Way, but also for what it says about distant galaxies. Studies of Sgr B2 should help scientists better understand the conditions in galaxies at earlier cosmic times, some 3.5 billion years after the Big Bang, when the rate of star formation peaked.