Key Takeaways:

- Lunar astrophotography is highly accessible, accommodating a range of telescope types and cameras, and leverages the Moon's brightness to enable short exposure times.

- Optimal image acquisition often employs the "lucky imaging" technique, capturing high-frame-rate video to overcome atmospheric turbulence, with the SER format recommended for its efficiency over compressed video types.

- Post-processing workflows typically involve software like SharpCap for capture, followed by AutoStakkert for sorting and stacking the highest-quality video frames, and AstroSurface for deconvolution to enhance detail.

- The most compelling lunar images are frequently captured along the terminator, highlighting features through shadows, with specific targets of interest including the transient Lunar X and Lunar V phenomena.

The Moon is the first celestial object to catch our eyes. For some amateur astronomers, it quickly becomes a bother, its light obscuring the “faint fuzzies” we try to catch in our telescopes. Or, like me, you may feel drawn to photograph its cratered surface, which reveals a different character each night. The good news is that you don’t have to wait for a perfect night.

You can use just about any telescope to image the Moon. Long-focal-length instruments will uncover more detail. Shorter reflectors, fast refractors, and even camera lenses can see the whole surface at once. It’s helpful to have a tracking mount, especially for long reflectors, but it’s not necessary to capture a sharp image — just reduce the exposure time to eliminate motion blur as the Moon drifts through the field of view.

You also can use just about any camera. There are many affordable, uncooled astro cameras specifically for solar system imaging, such as those from ZWO or the QHY5 series, which typically cost between $150 and $350. You can also use a DSLR, like I did in my early days, although that can be tricky for reasons that will soon become clear.

My favorite software for capturing lunar images is SharpCap, which lets you take either individual images or video. Rather than snapping still frames, most solar system imagers capture video using a process called “lucky imaging.” The atmosphere’s turbulence blurs our view, but there are often moments when the sky is steady. A camera running at a high frame rate can capture those. Post-processing in software like AutoStakkert sorts the video frames by quality and averages only the best frames. Following that with deconvolution in software like AstroSurface recaptures the detail lost to the atmosphere using some fancy mathematical algorithms. Of course, nights with better seeing will yield better results, but only patience and persistence are required to capture sharp images.

Because the Moon is bright, you will need to use short exposure times. With my 8-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain and my ZWO ASI183MC camera, this is usually around 10 milliseconds, although the exact exposure time varies by telescope, camera, sky conditions, and Moon phase. There are different schools of thought about how many frames one should capture and stack, but I usually shoot 1,000 frames and stack the best 10 percent. I recommend recording videos in the SER format, which is like the astronomy raw-image FITS file type, but for video. There are SER video players on the internet, and image-processing software can handle SER more easily than formats with a messy ecosystem of codecs like AVI. This is why DSLRs can be difficult to work with for solar system imaging — you have to deal with video compression artifacts and a variety of video codecs, as well as shutter vibration.

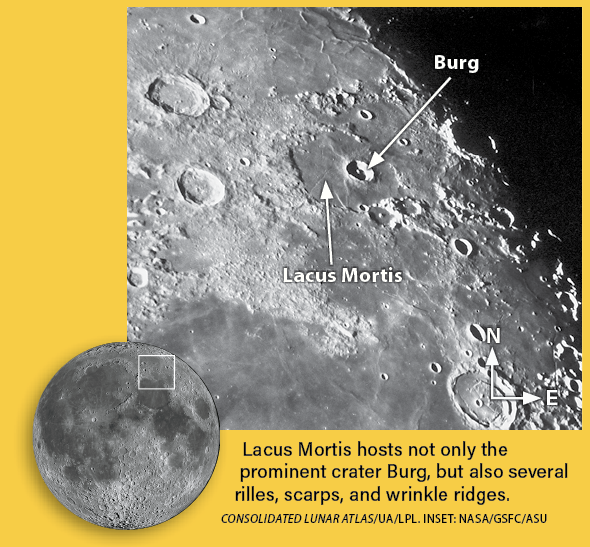

The most compelling lunar images are usually along the terminator, the dividing line between lunar day and night. Here, crater rims and mountains cast long shadows, starkly illuminating the Moon’s rugged surface and making for striking views. Try your hand at capturing the Lunar X feature — a clair-obscur effect where crater rims form the shape of an X, only visible for a few hours before First Quarter, about halfway between the equator and south pole. You can also try to capture the Lunar V farther up the terminator, just above the equator.

Rather than avoiding observing while the Moon is in the sky, use that time to snap beautiful images of our celestial companion. There’s always something new to explore (and share), whether you’re chasing a slender crescent or the fully-illuminated surface. Every clear night is a gift — even when the Moon is out.