Key Takeaways:

- Mars, at magnitude 1.6, will be visible in the western sky, passing near Spica on September 12th. Its small apparent diameter will limit telescopic detail.

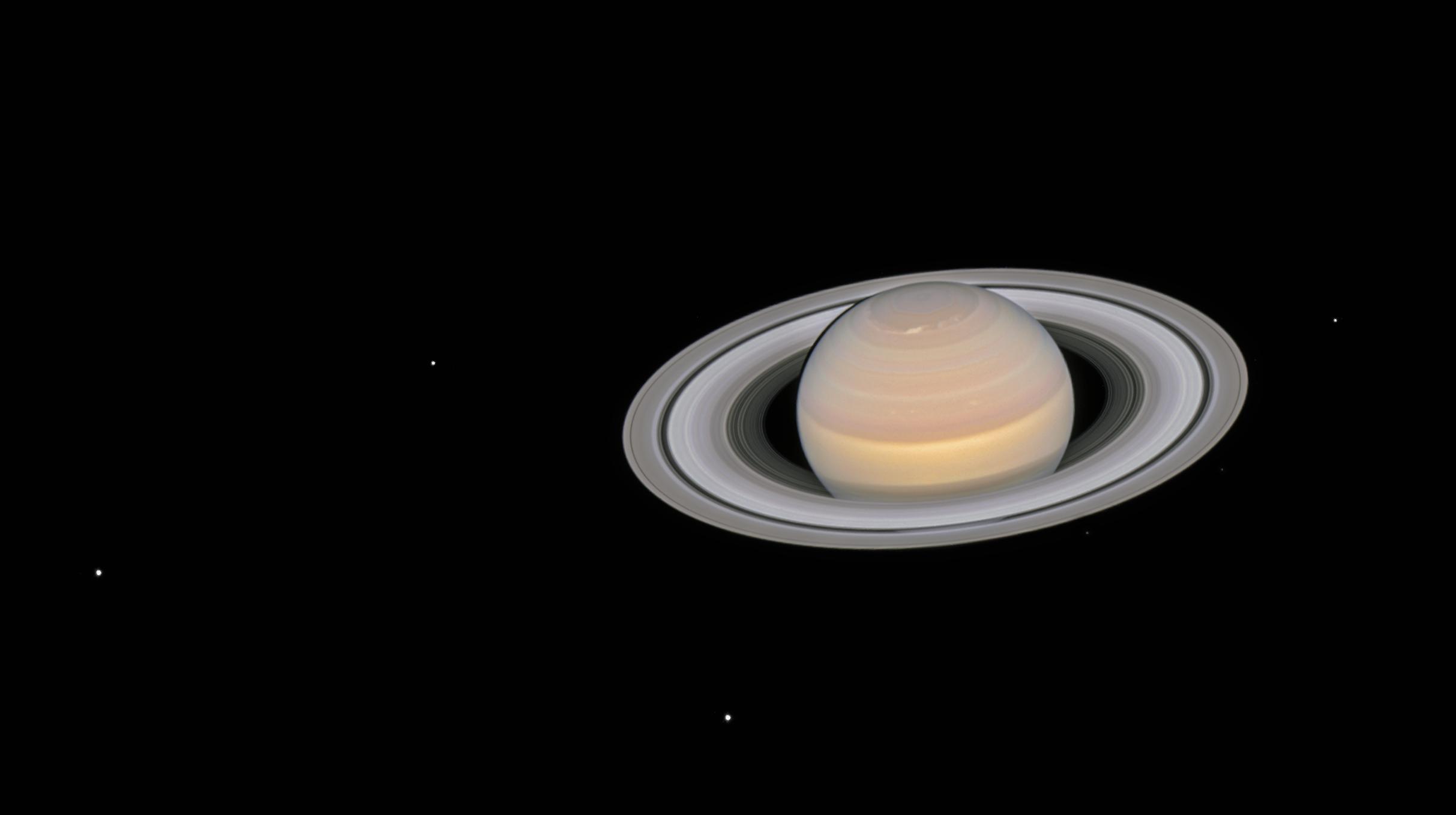

- Saturn reaches opposition on September 21st, offering optimal viewing conditions all night. At opposition, its apparent size will be maximized, with rings spanning 44.1".

- Jupiter, at magnitude –2.0, will be prominent in the northeastern sky, showcasing visible equatorial belts through even small telescopes.

- Venus, at magnitude –3.9, will appear in the east at dawn but telescopic observation will reveal only a large gibbous phase; Mercury will be unobservable due to superior conjunction.

The evening sky boasts two naked-eye planets. Start your night’s viewing with ruddy Mars, which lies in the west as darkness falls. It treks eastward against the backdrop of Virgo, passing 2° north of the Maiden’s brightest star, 1st-magnitude Spica, on Sept. 12. The Red Planet shines at magnitude 1.6, slightly fainter than the blue-white star.

Mars lies far from Earth, unfortunately, so it doesn’t look like much through a telescope. It sports a featureless disk 4″ in apparent diameter.

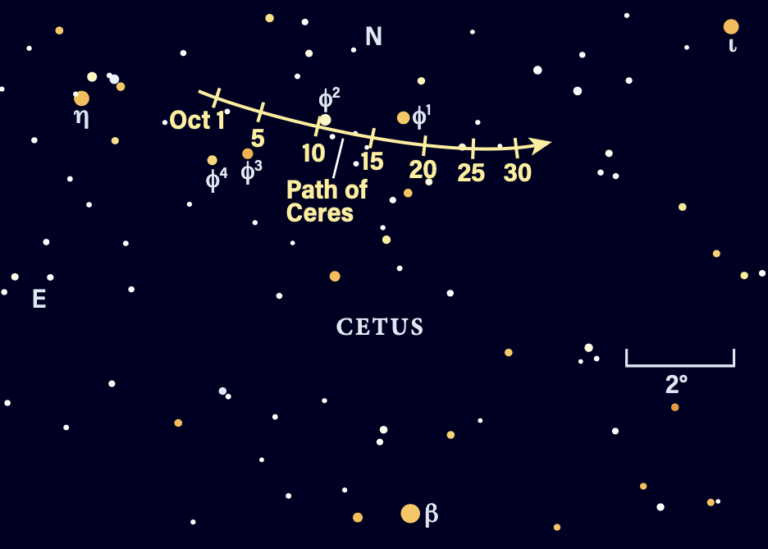

On the other side of the evening sky resides September’s gem, Saturn. The ringed world reaches opposition and peak visibility Sept. 21, when it lies opposite the Sun in our sky and remains visible all night. The magnitude 0.6 planet moves slowly westward against the background stars of southern Pisces this month, crossing into Aquarius on the 29th.

At opposition, Saturn has a declination of –3°. After many years of oppositions occurring in the southern celestial hemisphere, this is the last time it will happen until March 2040.

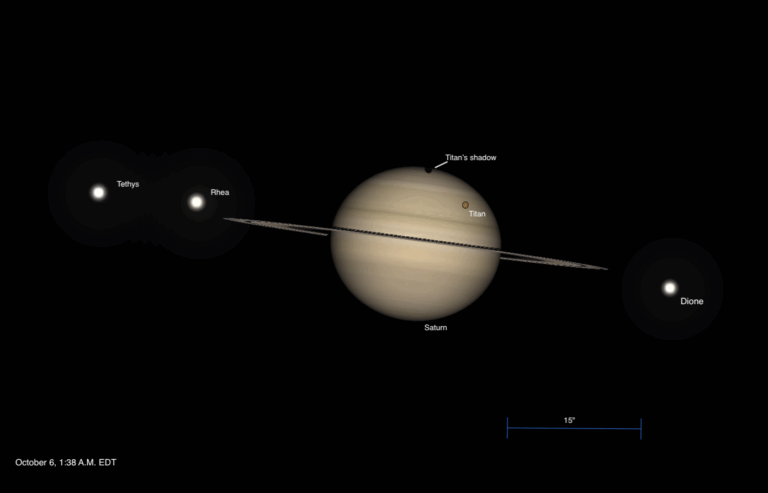

Opposition also coincides with the planet’s closest approach to Earth, so it looms largest when viewed through a telescope. On the 21st, Saturn’s disk measures 19.4″ across while the ring system spans 44.1″ and tilts 1.8° to our line of sight. Saturn’s four brightest moons — 8th-magnitude Titan and 10th-magnitude Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — also should be easy to see.

As Saturn starts to descend in the west during the morning hours, Jupiter emerges in the northeast. The giant planet resides in Gemini and appears directly below the distinctive figure of Orion the Hunter. Gleaming at magnitude –2.0, it outshines every star in the night sky.

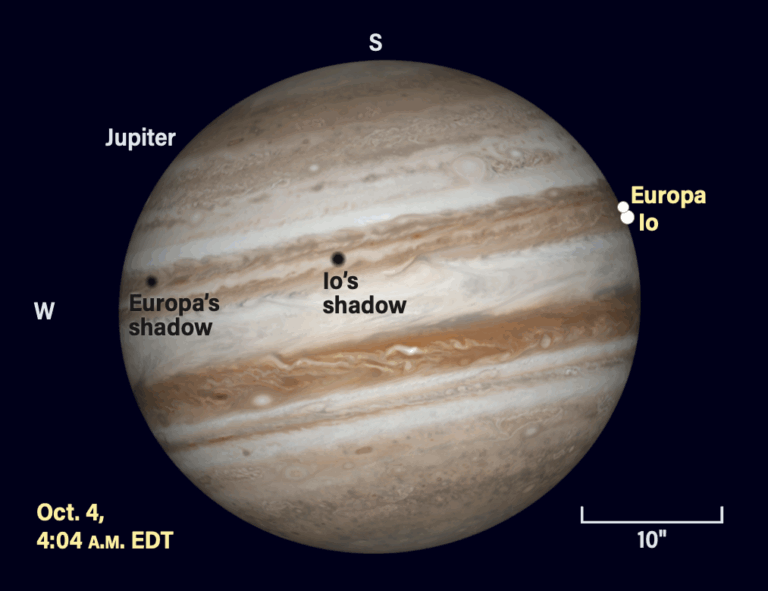

Once Jupiter stands well clear of the horizon, aim your telescope in its direction. Even small instruments should reveal two dark equatorial belts arrayed across the planet’s 35″-diameter disk. And Jupiter’s four bright moons show up as points of light (assuming none are passing in front of or behind the gas giant).

Around the time twilight starts to paint the sky, Venus pokes above the eastern horizon. Shining at magnitude –3.9, the inner world proves unmistakable even as twilight grows brighter. Unfortunately, it looks disappointing through a telescope, showing a disk 12″ across and a fat gibbous phase.

Mercury reaches superior conjunction Sept. 13 and remains hidden in the Sun’s glare nearly all month. It will put on a nice evening show in October.

A total lunar eclipse graces the skies above Australasia, Asia, and Africa on Sept. 7. The umbral part of the eclipse begins at 16h27m UT (the morning of the 8th from Australasian latitudes). Totality runs from 17h30m to 18h53m UT, and the umbral phase ends at 19h57m UT.

A partial solar eclipse takes place Sept. 21 and can be seen from New Zealand and much of the South Pacific Ocean. From Wellington, the eclipse starts soon after sunrise on the 22nd. It reaches a maximum at 19h04m UT, when the Moon covers 74 percent of the Sun’s diameter. The eclipse concludes at 20h15m UT.

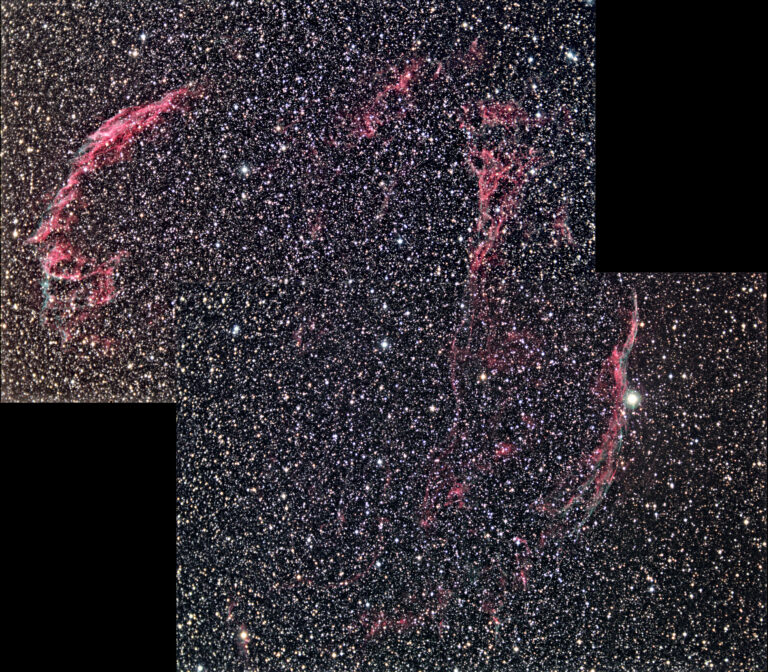

The starry sky

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) approved official constellation boundaries nearly a century ago. So, you might be surprised that the organization did not start approving proper names of stars until 2016. Of course, hundreds of star names were in common use long before then. For example, on September evenings we can gaze at Antares (the “rival to Mars”), Altair (Aquila’s luminary), and Spica (which Mars passes in the middle of the month), among many others.

I was thinking not long ago about not only the great number of named stars in some constellations but also how some constellations have few named stars — at least in the current IAU list. This led me to wonder how many constellations have no officially named stars, and I was surprised to find 14 of these stellar groupings. Remember that 88 constellations spread across the sky, so this number represents 16 percent of the total. It amazed me even more that an additional 16 constellations have only one star with an IAU proper name.

Those first 14 all lie in the southern half of the celestial sphere. The constellations are Caelum, Circinus, Horologium, Hydrus, Indus, Lupus, Microscopium, Musca, Norma, Pictor, Pyxis, Scutum, Telescopium, and Volans.

How about the 16 constellations with only one IAU-approved star name? The majority of these also reside in the sky’s southern half. People often ask me about one of them — Corona Australis the Southern Crown — even when I do not draw attention to it during a planetarium presentation. And it’s easy to see why: After gazing at Scorpius, a dark-adapted eye quickly spots the faint circlet of stars immediately east of the Scorpion’s tail.

The star designated Alpha (α) Coronae Australis has the proper name Meridiana, a rather odd name suggesting that it has something to do with a meridian. This Latin name, however, can be translated as south, a shortened version of the longer name Alfecca Meridiana. This separates it from Alphecca, the brightest star in the Northern Crown (Corona Borealis). A connection does exist with a meridian, though, in the sense that people in the Northern Hemisphere see the Sun due south when it lies on the meridian.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 30° south latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

10 p.m. September 1

9 p.m. September 15

8 p.m. September 30

Planets are shown at midmonth