Key Takeaways:

- Beverly Lynds' catalog of dark nebulae (LDNs) is a crucial resource for astronomers.

- Existing methods for identifying LDNs in images are often inaccurate.

- A new project is digitally annotating Lynds' original tracings to improve LDN identification.

- This improved identification will help astronomers and astrophotographers more accurately label images.

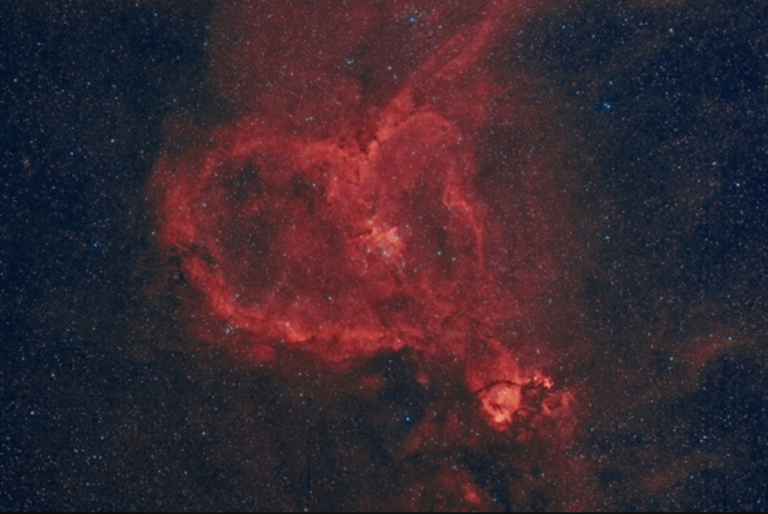

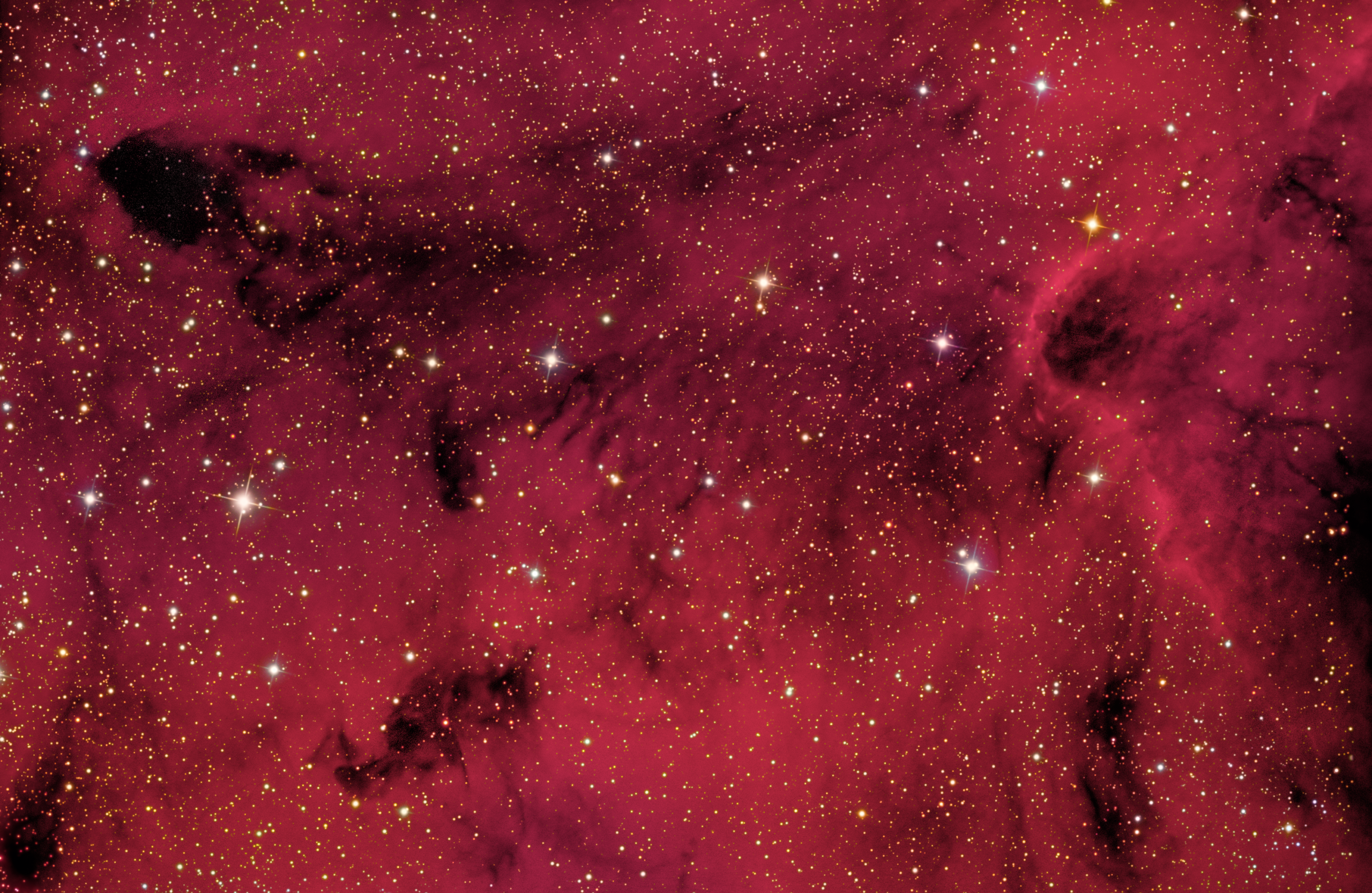

If you are a frequent reader of Astronomy, then you likely have seen images on its pages of objects from the famous Lynds’ Catalogue of Dark Nebulae. These mysterious dark clouds of interstellar dust are denoted by the letters LDN followed by a catalog number, such as LDN 881.

I have contributed some of those images. I and many other astroimagers have also contributed images of bright nebulae that happen to contain LDN objects. While the LDNs aren’t always mentioned in the captions, their presence provides stark contrast that certainly makes those images more dramatic and captivating. For example, the North America Nebula (NGC 7000) wouldn’t resemble that continent so strongly if it didn’t have LDN 935 posing as the Gulf of Mexico.

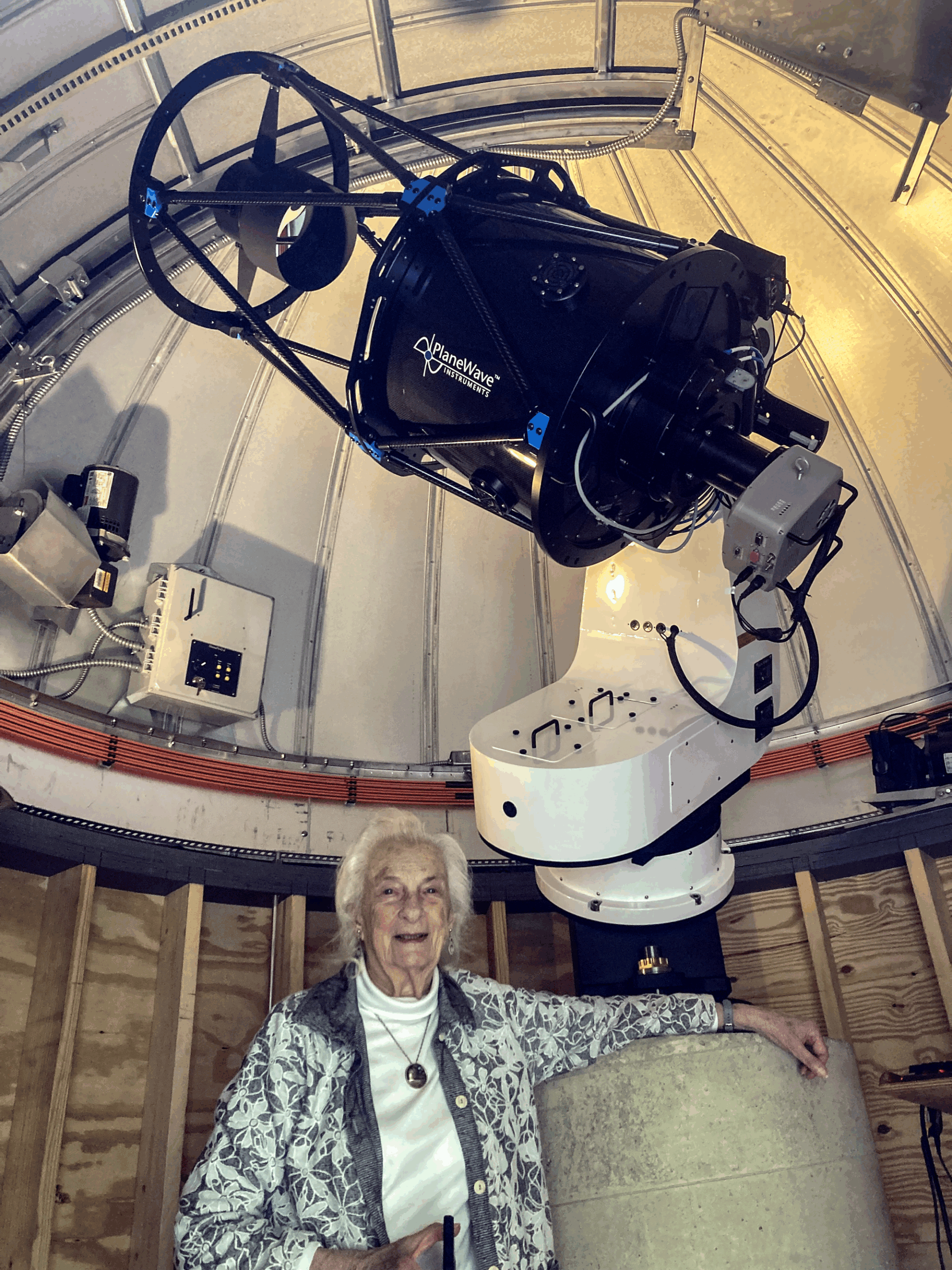

The Lynds’ Catalogue of Dark Nebulae was compiled by American astronomer Beverly Turner Lynds, who died peacefully at a hospice in Portland, Oct. 5, 2024, after suffering a stroke in early September. She was 95 years old. I am honored to say that Beverly was one of my nearest and dearest friends.

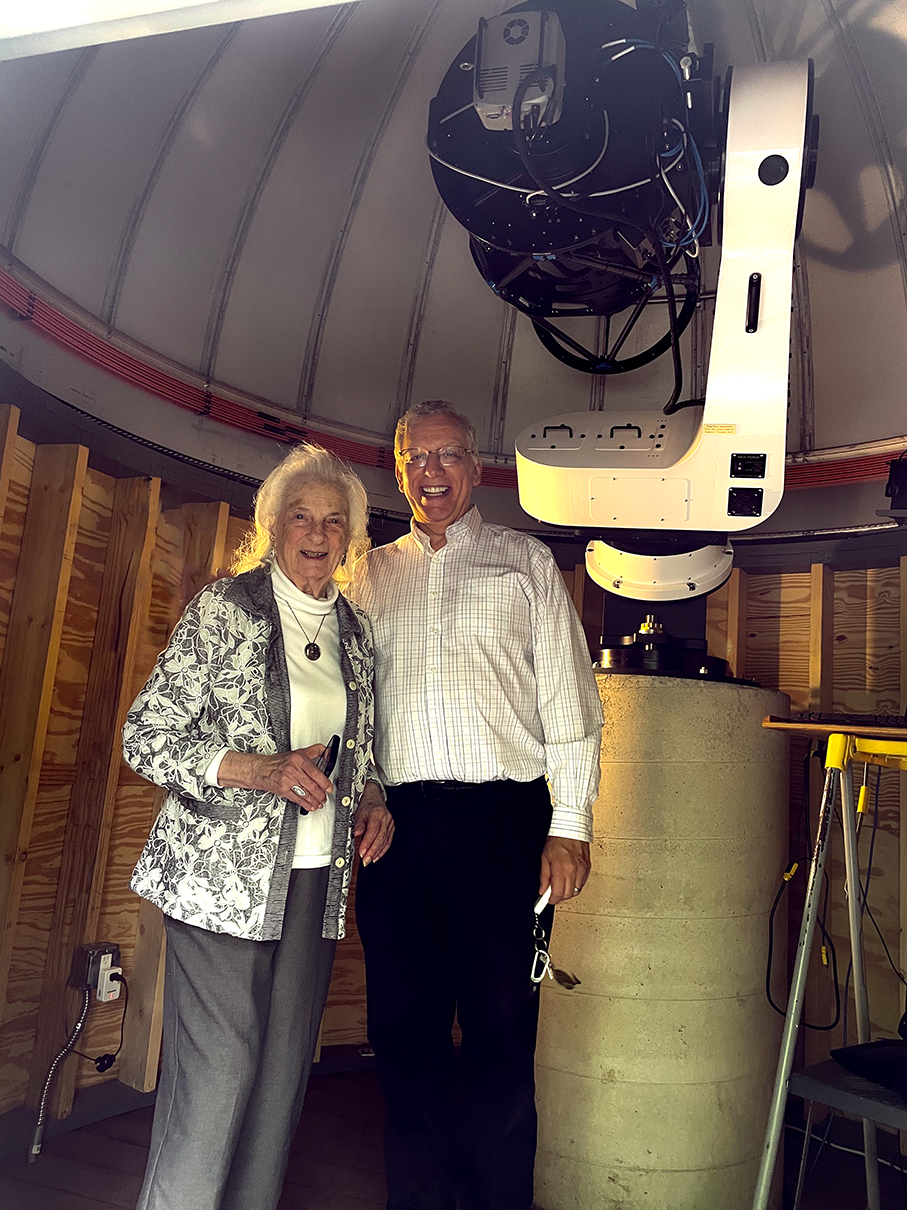

While researching her, I had been pleasantly surprised to discover she lived only a few miles from me. I contacted her and was delighted to hear she knew about me from reading my articles in Astronomy. She knew from my article bylines that I also live in Portland and wondered if we might meet.

After our first meeting, we immediately became best astronomy buddies. We regularly met for lunches at our favorite restaurants or our homes. We exchanged email messages almost daily and she loved visiting my backyard observatory. She would entertain me for hours with stories about all the famous astronomers she knew and with whom she had worked.

More importantly, I learned a great deal about her remarkable life and am delighted to tell her story, and the story behind her dark nebulae catalog, here.

A storied career

Beverly Turner was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, on Aug. 19, 1929. Her family moved to New Orleans when she was three, but she later returned to Shreveport to attend Centenary College of Louisiana, where she decided to become a professional astronomer. She applied to four graduate astronomy programs and was admitted to three, but shortly after she accepted the position at the University of Chicago, the offer was withdrawn when they discovered she was a woman. (Beverley can be a man’s name if spelled with a third E.) The other two programs adopted the same stance.

To strengthen her next round of applications, Lynds took additional college astronomy courses and obtained a position as assistant at Lick Observatory near San Jose, California, where she assisted Nicholas Mayall in measuring the radial velocities of galaxies and George Herbig (of Herbig-Haro objects) with spectroscopic programs using the 36-inch refractor. She was subsequently admitted to the graduate astronomy program at the University of California, Berkeley, and earned a Ph.D. in 1955 with her thesis on the spectra of white dwarfs. During this time, she married fellow graduate astronomy student C. Roger Lynds in 1954.

In 1960, the Lyndses moved to the new National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Greenbank, West Virginia, where she assisted its director, Otto Struve (whose great-grandfather, Friedrich, compiled the Struve double star catalog), with writing an astronomy textbook. Struve also charged her with building an astronomy library from scratch, an important resource for observatories prior to the internet. She ordered a copy of the recently completed National Geographic Society–Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (1958), which was obtained with Palomar’s 48-inch Schmidt telescope. The survey covers the sky north of –33° declination. When it arrived, Lynds immediately noticed how well dark nebulae showed up on its plates. She decided she could compile a catalog of dark nebulae that would be superior to that published by Edward Emerson Barnard in 1927.

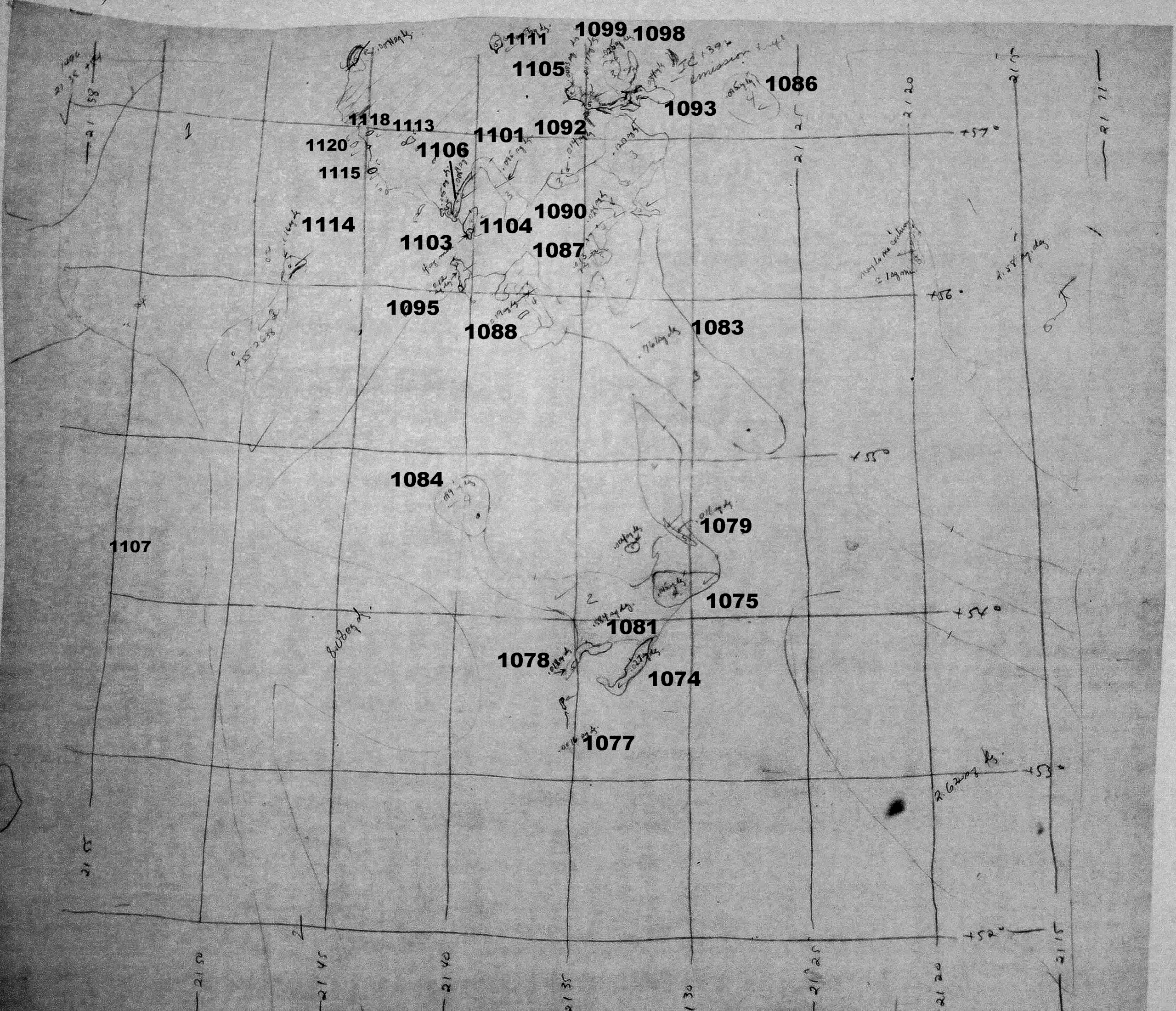

Lynds spent hours tracing the outline of each dark nebula visible on the plates onto sheets of tracing paper. She recorded their epoch B1950.0 coordinates, measured their area in square degrees with a calibrated planimeter, and estimated their darkness on a scale of 1 to 6.

Her catalog of 1,802 dark nebulae, published in the Astrophysical Journal in 1962, far surpassed Barnard’s and is now regarded as a landmark catalog on par with the Messier, New General, Index, and Sharpless catalogs. It currently has nearly 1,000 citations in the scientific literature. She subsequently repeated this process with emission and reflection (but not planetary) nebulae as well as supernova remnants, publishing her catalog of bright nebulae in the Astrophysical Journal in 1965.

She went on to study the association between dark and bright nebulae, finding their relationships easier to analyze in other galaxies than from our limited view within a spiral arm of the Milky Way. Allan Sandage lent her Edwin Hubble’s glass plate images of galaxies to conduct this work. Astronomer C.C. Lin found her work supportive of his density wave theory for the formation of spiral arms in galaxies.

She subsequently studied the dust in the Trifid Nebula (M20) using the then-new technology of CCD imaging. In 1976, Lynds became Assistant Director of Kitt Peak National Observatory in Tucson, Arizona.

After retirement, she devoted much of her time to science education and reducing racial and gender disparities in the field. She served as a Shapley Lecturer for the American Astronomical Society, specifying she only wanted to visit minority colleges. She won the education award from the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research in 2013.

The gift of legacy

Since the beginning of our friendship, Beverly showered me with astronomy gifts, including signed books from her library, reprints of papers she published, one of Frank Drake’s wine glasses with his famous Drake equation on it, and Otto Struve’s personal copy of Sven Cederblad’s Catalog of Bright Diffuse Galactic Nebulae (1946).

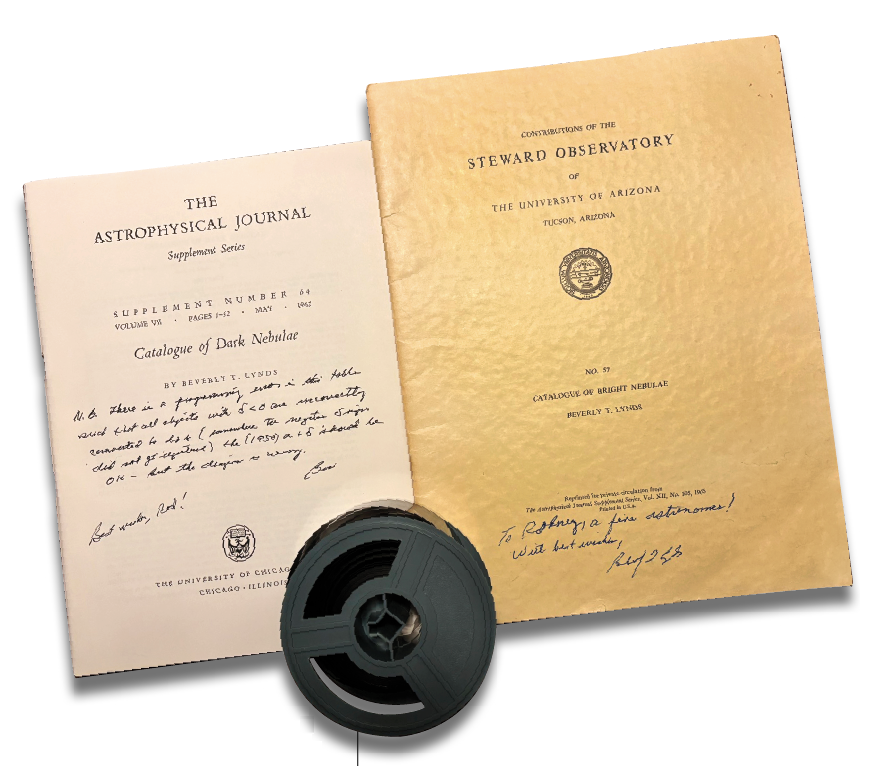

Two especially precious gifts are original editions of the Astrophysical Journal issues containing her dark nebulae and bright nebulae catalogs, which she personally autographed to me.

But her most remarkable gift to me was a reel of microfilm containing images of the sheets of tracing paper from which she made her dark nebulae catalog. As far as she knew, this is the only surviving copy of her original tracings.

I immediately recognized it as a historic astronomical treasure and knew I needed to ensure its preservation. However, I also thought I should try to do something significant with it. For preservation, I digitally scanned each microfilm frame, made multiple copies of the files, and stored them in different locations. But what could I do that would be a significant new contribution?

The problem of identification

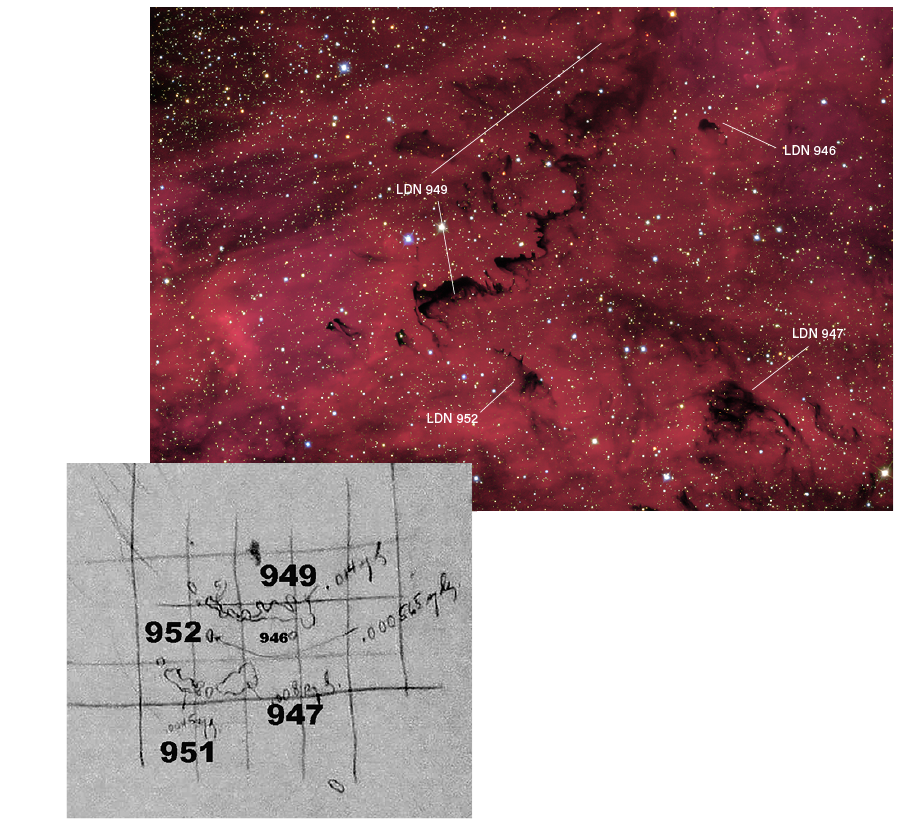

Examining Lynds’ tracings, I saw that she drew some lines of right ascension and declination on each. She wrote her measured area of each dark nebula next to its traced outline and recorded her assessment of its darkness on her scale of 1 to 6 within its outline.

She put a checkmark next to an outline to indicate she had included it in her catalog. What surprised me is that she never recorded a single catalog number next to any of the dark nebulae’s traced outlines. This left me wondering as I gazed at any of her tracing sheets: “Which dark nebulae are these?”

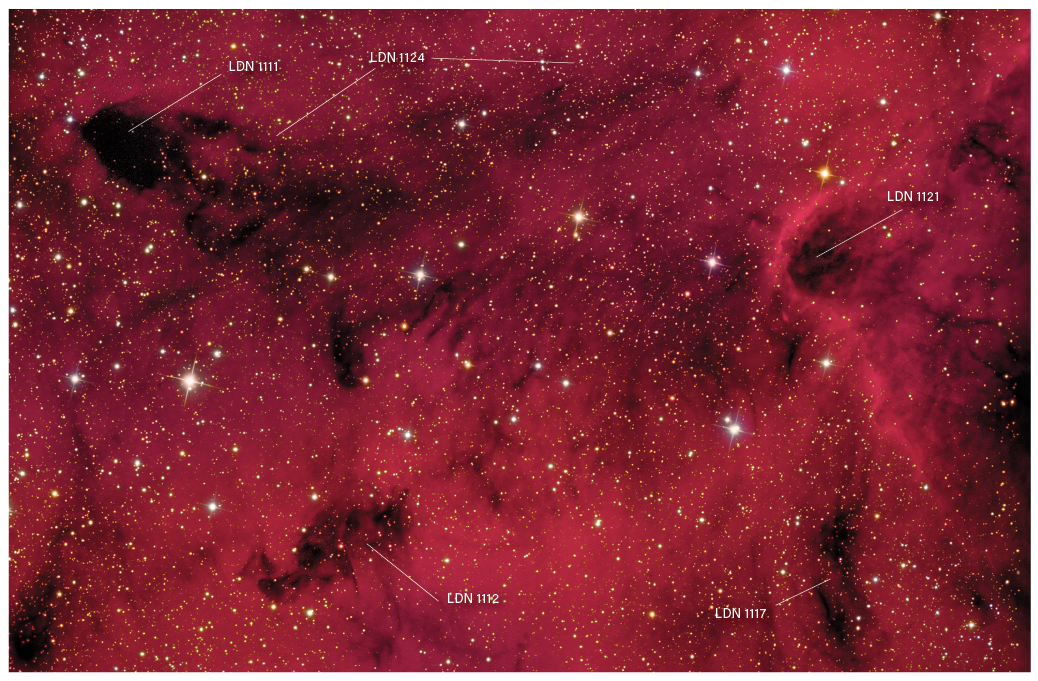

The Lynds’ Catalogue of Dark Nebulae is not photographic. It’s all text and the objects are in no particular order. So who knows what the actual shapes of, say, LDNs 128, 437, 1121, and 1795 are? Apart from a few of the most frequently imaged LDNs, most are unfamiliar to us. Their recorded areas in square degrees are of no help in estimating their shape because a dark nebula with an area of, say, 0.25 square degrees could be a circular globule or a long, drawn-out filament. The area alone gives no clue.

The problem of LDN identification is more ubiquitous than you might think. I have seen many published images in which the LDN number listed in the caption is clearly incorrect. This isn’t surprising, as resources to help imagers correctly identify LDNs are inadequate.

For example, when I use PixInsight software to plate solve and annotate my images containing LDNs, the program places labeled circles on the image intended to identify the LDNs, but they are always considerably offset from them. The centers of the circles don’t match their 1950 coordinates in the catalog, so precession doesn’t explain this problem. If the offset of a circle happens to place it just outside the field of view, then no identification is made. And the circles are sometimes not large enough to encompass the entire LDN.

When there are several LDNs on an image, I can identify them by matching the pattern of the circles’ arrangement with the locations of the dark nebulae, but this can be difficult and confusing. Similarly, when I look up LDNs on the online photographic Aladin Sky Atlas, it often puts the identification crosshair over a blank region of background sky between several dark nebulae.

So, which of the many dark nebulae on the screen is the one that I want? Sometimes I can’t see the size or shape of a dark nebula because the Aladin image is so underexposed that I can’t discern the difference between the nebula and the background sky, even with contrast turned up to maximum. Still other times, it simply misidentifies dark nebulae altogether.

The solution

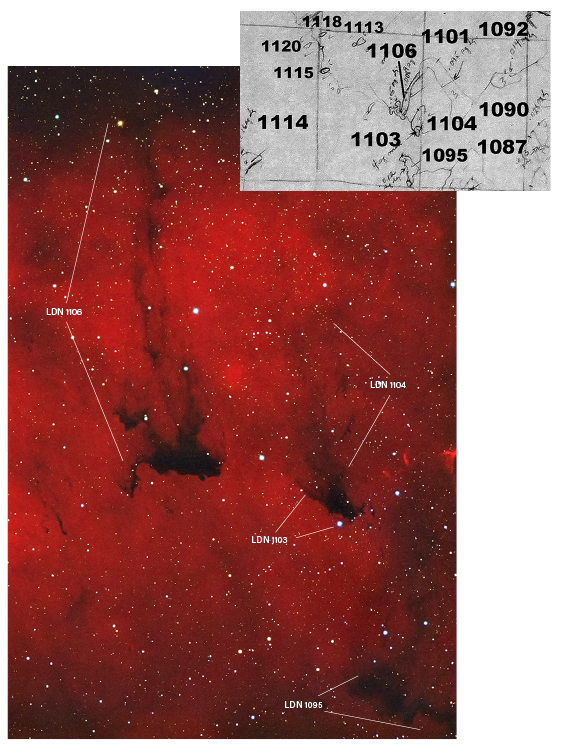

I realized the significant contribution I could make would be to identify and label each original tracing outline with its correct LDN number directly on my scanned images. Then, we would know the actual shape of each LDN based on Lynds’ original tracings. This would enable correct identification of an LDN in an image by direct comparison of its shape with the shape on her original tracing.

To accomplish this, I open one of my scanned digital images of a tracing sheet in Photoshop. Next, I determine its rough coordinates based on the lines of right ascension and declination Lynds drew on the sheet. Then I browse the published catalog and begin to identify each dark nebula outline on that sheet by roughly matching the coordinates of its center with an LDN listing.

If both its area in square degrees and its darkness rating as written on the sheet for that outline by Lynds herself also match that listing in the catalog, then its identity is confirmed. Once identified, I label the traced outline on the scanned image with its correct LDN number using the Type Tool in Photoshop. After all the dark nebulae on that image have been identified and labeled, I save the file as a new annotated version.

I have devoted many hours to this project and it will take many more to complete; some tracings of regions of the summer Milky Way have perhaps 100 dark nebulae per sheet. But once it is completed, we will have a visual resource that correctly identifies each LDN object and shows its shape just as Lynds originally defined it.

I intend to make the collection of annotated images available as a resource accessible to all astronomers and astroimagers, amateur and professional. The editors of Astronomy have offered to post it on Astronomy.com. I also have visited with and offered a copy to the librarian of the Royal Astronomical Society in London, who views it as an extremely valuable contribution to its considerable historical holdings.

One last puzzle

In her final years, Lynds endeavored to determine who might have been the astronomer in Walt Whitman’s poem When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer, which was one of her favorites. She researched this extensively to solve the mystery. She sent me frequent email updates on her progress, ultimately culminating in her final opinion: astronomer Ormsby Macknight Mitchel, the first American popularizer of astronomy. Here’s the poem:

When I heard the learn’d astronomer,

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me,

When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them,

When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer

by Walt Whitman

Rest in peace Beverly, my dear friend. We will always remember your tremendous contributions to astronomy.