Friday, September 8

Jupiter has been a conspicuous evening object for the past several months, but it’s nearing the end of its reign. The giant planet lies about 10° high in the west-southwest 45 minutes after sunset. Still, at magnitude –1.7, it shines brightly enough to appear prominent against the twilight glow. If you view Jupiter through binoculars this evening, you’ll also see 1st-magnitude Spica 3° to its lower left. The planet appears 12 times brighter than the star. A telescope easily shows Jupiter’s four bright moons, but the planet’s low altitude means you won’t see crisp details on its 32″-diameter disk.

Saturday, September 9

The constellations Ursa Major the Great Bear and Cassiopeia the Queen lie on opposite sides of the North Celestial Pole, so they appear to pivot around the North Star (Polaris) throughout the course of the night and the year. In late August and early September, these two constellations appear equally high as darkness falls. You can find Ursa Major and its prominent asterism, the Big Dipper, about 30° above the northwestern horizon. Cassiopeia’s familiar W-shape, which currently lies on its side, appears the same height above the northeastern horizon. As the night progresses, Cassiopeia climbs above Polaris while the Big Dipper swings below.

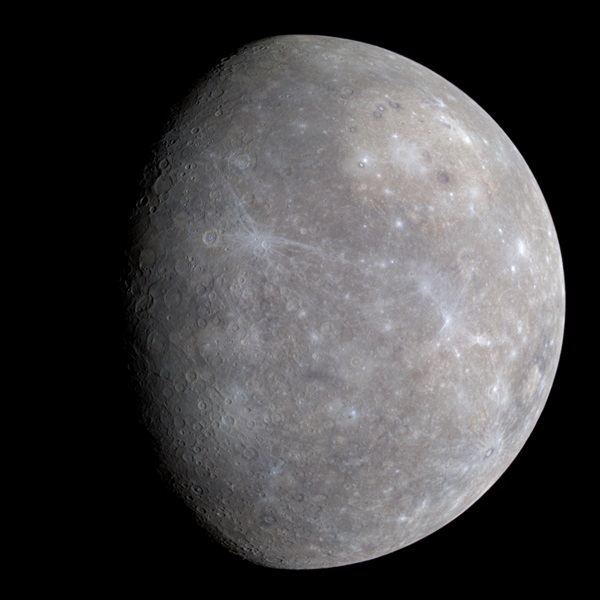

Sunday, September 10

A week ago, Mercury was a binocular object low in the east during morning twilight. It now appears much more conspicuous — shining at magnitude –0.1 and climbing 10° high 30 minutes before sunrise. This morning, the innermost planet passes 0.6° due south of the 1st-magnitude star Regulus, while ruddy Mars stands 3° to the pair’s lower left. All three objects show up nicely in a single binocular field.

Monday, September 11

Although Neptune appeared at its best at opposition seven days ago, its visibility hardly suffers this week. The outermost major planet lies low in the southeast as darkness falls and climbs highest in the south around midnight local daylight time. Neptune glows at magnitude 7.8, which is bright enough to spot through binoculars if you know where to look. The trick is to find the 4th-magnitude star Lambda (l) Aquarii, which lies about 10° southeast of Aquarius’ distinctive Water Jar asterism. This week, Neptune appears 1.0° east of this star. When viewed through a telescope, Neptune shows a blue-gray disk measuring 2.4″ across.

Tuesday, September 12

Mercury makes an impressive appearance before dawn in mid-September. It reaches greatest elongation this morning, when it lies 18° west of the Sun and appears 11° high in the east 30 minutes before sunrise. The innermost planet shines at magnitude –0.4 and is the most conspicuous celestial object near the eastern horizon. If you scan this region with binoculars, you’ll also see the 1st-magnitude star Regulus some 2° above Mercury and the ruddy glow of Mars 3° to Mercury’s lower left.

Wednesday, September 13

Last Quarter Moon arrives at 2:25 a.m. EDT. It rose in the east-northeast late yesterday evening (shortly before midnight) and climbs high in the east before dawn. During this period, our half-lit satellite lies among the background stars of eastern Taurus the Bull.

The Moon reaches perigee, the closest point in its orbit around Earth, at 12:06 p.m. EDT. It then lies 229,820 miles (369,860 kilometers) from Earth’s center.

Thursday, September 14

Any clear evening during the first half of this week is a good time to explore the constellation Sagittarius the Archer. This star group lies due south and at peak altitude around 8:30 p.m. local daylight time, near the time twilight ends. The brightest stars within the constellation form a distinctive asterism in the shape of a teapot. The central regions of the Milky Way pass through Sagittarius, so it’s always worth exploring the region through binoculars or a telescope.

Friday, September 15

Although Saturn reached opposition three months ago today, it remains a tempting target in the evening sky. The ringed world stands some 25° high in the south-southwest as twilight fades to darkness and doesn’t dip below the horizon until close to midnight local daylight time. Saturn shines at magnitude 0.5 against the backdrop of southern Ophiuchus, a constellation whose brightest star glows six times fainter than the planet. When viewed through a telescope, Saturn’s globe measures 17″ across while its spectacular ring system spans 38″ and tilts 27° to our line of sight. As you gaze upon Saturn from afar this evening, it’s the first time in more than 13 years that the Cassini spacecraft is not observing the ringed planet from up close. The robotic probe burned up in the gas giant’s atmosphere earlier today.

Saturday, September 16

Mercury and Mars have appeared near each other in the predawn twilight all week, but they make their closest approach this morning. For North American observers, they slide just 0.25° (half the Full Moon’s diameter) apart and lie in the same low-power field through a telescope. (Mercury spans 6.4″ and is about two-thirds lit; Mars is 3.6″ across and full.)

Sunday, September 17

The waning crescent Moon points toward three planets and a star this morning. The slim crescent stands 6° above Venus with Leo the Lion’s luminary, magnitude 1.4 Regulus, 3° below the planet. Mars and Mercury huddle 11° below Venus.

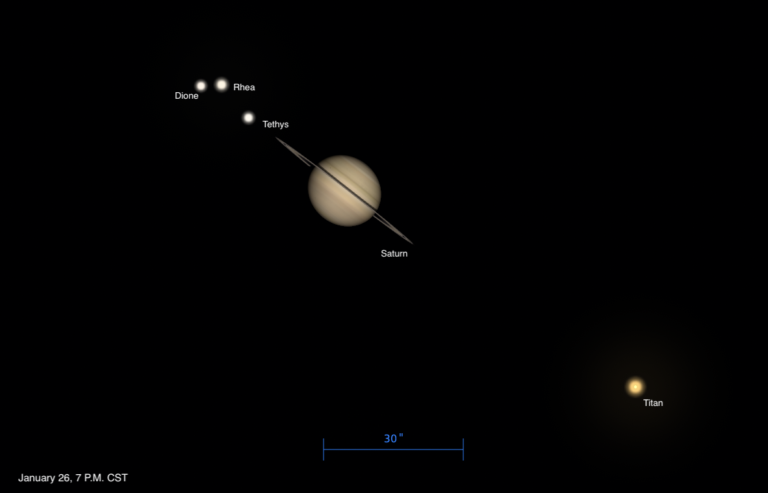

This evening provides a nice opportunity to see Saturn’s seven brightest moons through a telescope. The toughest to spot normally are the two inner ones — Mimas and Enceladus — which never stray far from the rings’ glare. But tonight, the two satellites reach greatest western elongation within two hours of each other. Tethys, Dione, Rhea, and Titan show up more clearly because they glow brighter and lie farther from the planet. Distant Iapetus rounds out Saturn’s “magnificent seven” satellites on display. If you draw a line from Saturn to 8th-magnitude Titan and extend it an equal distance, 11th-magnitude Iapetus will be right there.