A new analysis of Apollo-era quakes on the Moon reveal that our satellite is probably still tectonically active. Detectors laid down by Apollo astronauts half a century ago revealed small shakes on the Moon, but their causes weren’t well understood. Meteor strikes, like those that caused the Moon’s most distinctive features, still rain down today, so astronomers couldn’t be sure whether the Moon was shaking itself, or being shaken by external forces.

Now, new research has tracked the epicenters of each small moonquake, and found that eight of them could be traced to within 20 miles of so-called fault scarps. These are cliffs caused by the Moon’s surface shearing away from itself, thanks to long-term shrinking and contracting of the surface. Scientists know the Moon is too cold and still to have plate tectonics, like Earth, which keeps our whole crust sliding around in giant, continent-sized pieces. But the lunar faults, like Earth’s own fault lines, are similar in that occur where pieces of the surface sometimes rub against each other, causing quakes that can reverberate throughout the planet.

Moonquakes

What’s more, most of the Moonquakes occurred during times of the month when the tidal stresses between the Moon and Earth were at their greatest, which would make those faults more likely to slip and thus cause a quake. The Moon and Earth always tug on each other, but the stress on the faults is greatest when the Moon is at apogee, its farthest point from Earth. Researchers led by Thomas Watters, from the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C., published their findings Monday in Nature Geoscience.

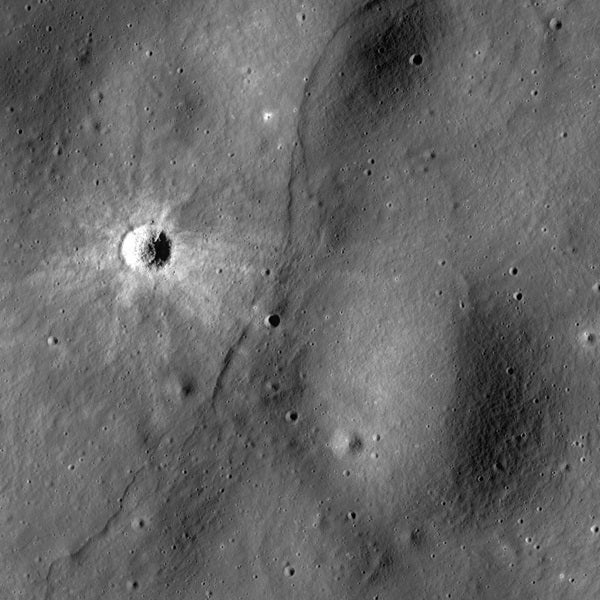

Researchers have long suspected the Moon might still be active. The quakes suggested it all on their own, though other forces can also shake the Moon. The fault scarps themselves are also a clue. If they were very old, from a much earlier period in the Moon’s history, then they would have filled in over the years with debris from crater impacts and other surface disruptions. So the fact that scientists see them clearly indicates they must be younger than 50 million years or so, an eyeblink in geologic time.

Watters and his team also looked carefully at data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and identified areas near the faults that look like they’ve been recently disturbed – boulders that have rolled in the near past, or evidence of landslides.

By tracing the moonquakes both in time and location to places where the Moon’s surface is most likely to be in motion, scientists are more certain than ever that the Moon is not dead yet, and is in fact still settling its own surface, and its interactions with its closest neighbor – our own Earth.