Key Takeaways:

It took astronomers a century to make the first-ever gravitational wave detection, confirming a core prediction of Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity. But this month, the floodgates have opened.

On Friday, scientists with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) announced they’ve likely detected a second gravitational wave event in as many days. Detectors at three locations around the world caught the arrival of a probable ripple in space-time around 11:20 a.m. E.T. It followed right on the heels of a gravitational wave detection Thursday that sent astronomers racing to observe the event with their telescopes.

In all, it’s the fifth gravitational wave detection this month. And the influx has astronomers excited about kickstarting the era of multi-messenger astronomy, where scientists can combine gravitational wave data with observations from conventional telescopes to gain new insights into extreme cosmic events like colliding black holes and neutron stars.

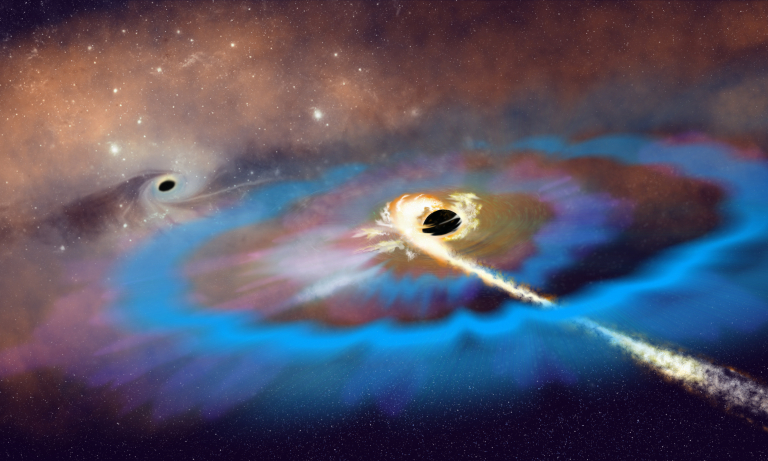

Scientists suspect Thursday’s event marked the second-ever gravitational wave detection of two colliding neutron stars, the collapsed cores left behind when giant stars go supernova. The merger would have likely spawned a new black hole. Astronomers spent Thursday searching for any signs of the collision on the sky. They’re less certain about the celestial event that led to today’s detection: There’s about a one in seven chance that it was a false alarm caused by earthly vibrations. Its signal is right at the threshold of what LIGO can pick out.

If this latest signal does turn out to be real cosmic collision, though, scientists say that there’s a chance it may be the hallmark of a never-before-seen event: the collision of a neutron star and a black hole. But odds still favor it as a third neutron star merger.

Searching for the light

LIGO consists of two L-shaped observatories — one in Louisiana and another in Washington state — that work by shooting a laser beam down the long legs of their “L” and watching for tiny disturbances caused by passing gravitational waves. Italy’s similar Virgo detector makes up the third part of the trio. LIGO first detected gravitational waves in 2016, winning its scientists the Nobel Prize in Physics. The collaboration then caught its first binary neutron star merger in 2017.

Unlike yesterday’s detection, which happened as one of the detectors was offline for 40 minutes, all three observatories caught today’s probable find. That makes it much easier to triangulate the event’s location in the sky and let astronomers train their telescopes on it. This time, the gravitational waves came from a location roughly 1.2 billion light-years away from Earth, astronomers say. That’s more than twice as far as the gravitational waves LIGO spotted Thursday.

Thursday’s observation kicked off a frantic effort by astronomers to find a sign of the corresponding collision in the night sky with telescopes. When neutron stars collide, the explosion is called a kilonova — a celestial event some 1,000 times brighter than a normal nova that astronomers can easily detect if LIGO tells them where to point their telescopes. And the ensuing high-energy mix of particles spawns enormous quantities of heavy elements, like gold and platinum. So watching the event in its first moments — and then seeing it evolve over time — can give scientists new insights into the aftermaths of these cosmic collisions.

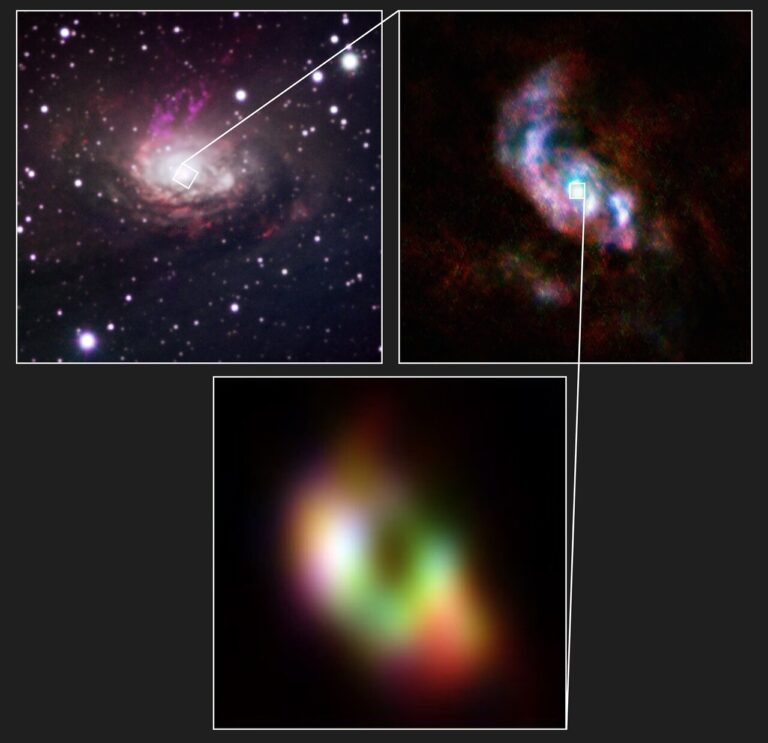

Astronomers around the world joined in and identified two potential candidates for Thursday’s neutron star merger. Their task was complicated by the fact that with just two detectors online, they could only narrow their search to about a quarter of the sky.

One of the potential candidates turned out to be a likely supernova, and it’s still unclear whether astronomers actually managed to find the source of the gravitational waves. Some astronomers may attempt to observe the source of today’s gravitational waves as well, though the associated uncertainty as to whether it’s a real gravitational wave event makes that a more difficult decision.

Third time’s the charm

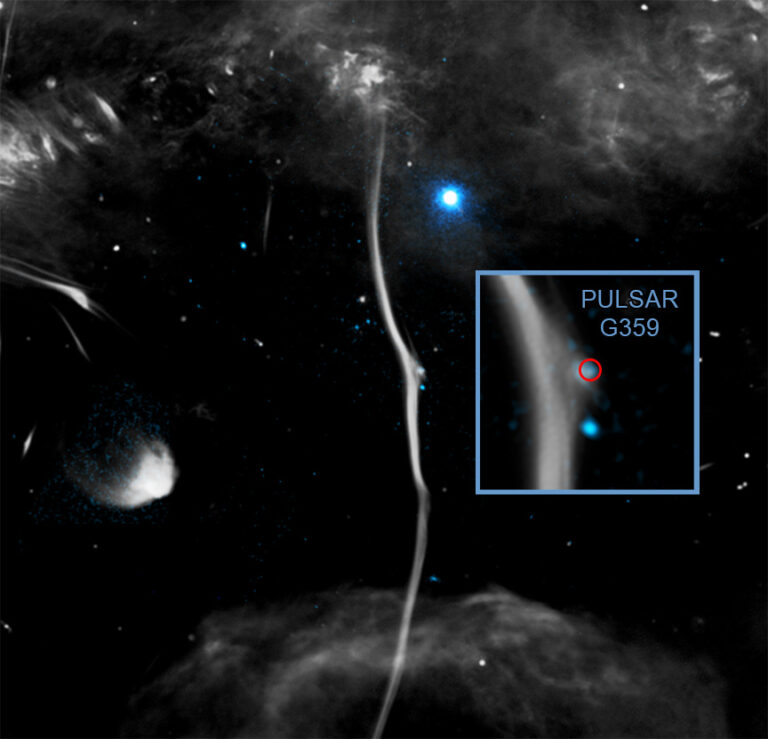

LIGO kicked off its third observing run on April 1 following an extended period when it was offline for upgrades. In just weeks, it’s also already detected three potential black hole collisions, bringing its total lifetime gravitational wave haul to 14.

Until this latest observing run, the LIGO collaboration kept its detections secret before they were peer-reviewed and published. That’s now changed. The public can follow along with the events in real time as detections come through. The team is posting each new gravitational wave observation online as a “circular,” where astronomers around the world can follow up with the results of their efforts to observe the event across the electromagnetic spectrum.

Now they’re eager for more opportunities.

Astronomers say that with LIGO’s upgraded abilities, they expect to see a gravitational wave about every week. And with two events in just two days, the deluge is just beginning.