Why did the hominin cross the plain? We may never know. But anthropologists are pretty sure that a smattering of bare footprints preserved in volcanic ash in Laetoli, Tanzania bear witness to an evolutionary milestone. These small steps, taken roughly 3.5 million years ago, mark an early successful attempt by our common human ancestor to stand upright and stride on two feet, instead of four.

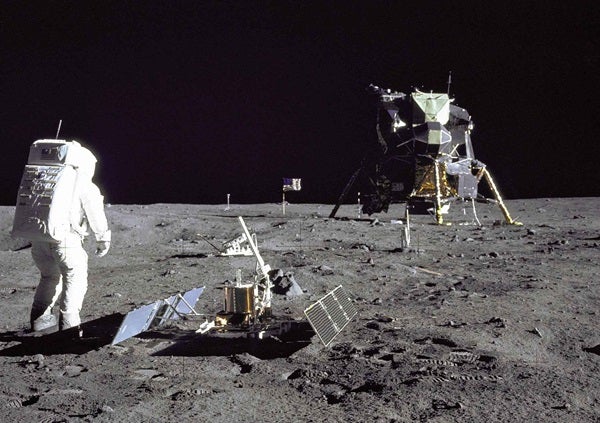

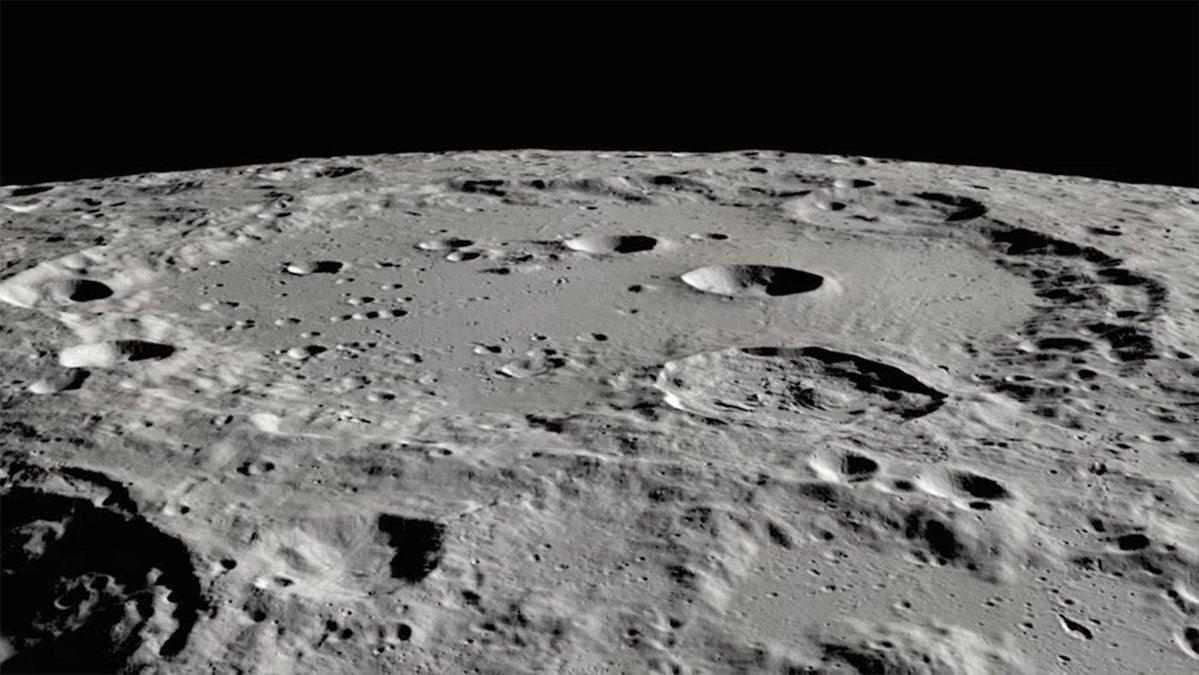

Nearly 50 years ago, Neil Armstrong also took a few small steps. On the Moon. His bootprints, along with those of fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin, are preserved in the lunar soil, called regolith, on what Aldrin described as the “magnificent desolation” of the Moon’s surface. These prints, too, bear witness to an evolutionary milestone, as well as humankind’s greatest technological achievement. What’s more, they memorialize the work of the many individuals who worked to unlock the secrets of space and send humans there. And those small steps pay homage to the daring men and women who have dedicated – and those who lost – their lives to space exploration.

The evidence left by our bipedal ancestors are recognized by the international community and protected as human heritage. But the evidence of humanity’s first off-world exploits on the Moon are not. These events, separated by 3.5 million years, demonstrate the same uniquely human desire to achieve, explore and triumph. They are a manifestation of our common human history. And they should be treated with equal respect and deference.

I’m a professor of aviation and space law and an associate director of the Air and Space Law Program at the University of Mississippi School of Law. My work focuses on the development of laws and guidelines that will assist and promote the successful and sustainable use of space and our transition into a multi-planet species. During the course of my research, I was shocked to discover that the bootprints left on the Moon, and all they memorialize and represent, are not recognized as human heritage and may be accidentally or intentionally damaged or defaced without penalty.

Heritage gets no respect

On Earth, we see evidence of this type of insensitivity all the time. The Islamic State has destroyed countless cultural artifacts, but it’s not just terrorists. People steal pieces of the Pyramids in Gaza and sell them to willing tourists. Tourists themselves see no harm in grabbing cobblestones that mark roads built by ancient Romans or snapping the thumbs off terra cotta warriors crafted centuries ago to honor a Chinese emperor.

And, just last year, Sotheby’s auctioned off a bag – the first bag that Neil Armstrong used to collect the first Moon rocks and dust ever returned to Earth. The sale was entirely legal. This “first bag” ended up in the hands of a private individual after the U.S. government erroneously allowed it to be included in a public auction. Rather than return the bag to NASA, its new owner sold it to the highest bidder for US$1.8 million. That’s a hefty price tag and a terrible message. Imagine how much a private collector would pay for remnants of the first flag planted on the Moon? Or even just some dust from Mare Tranquilitatis?

The fact is if people don’t think sites are important, there is no way to guarantee their safety – or the security of the artifacts they host. Had the first bag been recognized as an artifact, its trade would have been illegal.

Introducing ‘For All Moonkind’

That’s why I co-founded the nonprofit For All Moonkind, the only organization in the world committed to making sure these sites are protected. Our mission is to ensure the Apollo 11 landing and similar sites in outer space are recognized for their outstanding value to humanity and protected, like those small steps in Laetoli, for posterity by the international community as part of our common human heritage.

Our group of nearly 100 volunteers – space lawyers, archaeologists, scientists, engineers, educators and communicators from five continents – is working together to build the framework that will assure a sustainable balance between protection and development in space.

Here on Earth, the international community identifies important sites by placing them on the World Heritage List, created by a convention signed by 193 nations. In this way, the international community has agreed to protect things like the cave paintings in Lascaux, France and Stonehenge, a ring of standing stones in Wiltshire, England.

There are no equivalent laws or internationally recognized regulations or even principles that protect the Apollo 11 landing site, known as Tranquility Base, or any other sites on the Moon or in space. There is no law against running over the first bootprints imprinted on the Moon. Or erasing them. Or carving them out of the Moon’s regolith and selling them to the highest bidder.

Between 1957 and 1975, the international community did dedicate a tremendous amount of time and effort to negotiating a set of treaties and conventions that would, it was hoped, prevent the militarization of space and ensure freedom of access and exploration for all nations. At the time, cultural heritage in outer space did not exist and was not a concern. As such, it is not surprising that the Outer Space Treaty, which entered into force in 1967, doesn’t address the protection of human heritage. Today, this omission is perilous.

Because, sadly, humans are capable of reprehensible acts.

Back to the Moon

Currently there are a comparative trickle of companies and nations with their sights on returning to the Moon. China landed a rover on the far side in January. An Israeli company hopes to reach the Moon in March. At least three more private companies have plans to send rovers in 2020. The U.S., Russia and China are all planning human missions to the Moon. The European Space Agency has its sights on an entire Moon Village.

But as history shows, this trickle of explorers could soon become a rush. As we straddle the threshold of true space-faring capability, we have an extraordinary opportunity. We have time to protect our common heritage, humanity’s first steps, on the Moon before it is vandalized or destroyed.

If our hominin ancestor had a name, it is lost to history. Conversely, English novelist J.G. Ballard suggested that Neil Armstrong may well be the only human being of our time remembered 50,000 years from now.

If we do this right, 3.5 million years from now, not only will his name be remembered, his bootprint will remain preserved and the story of how Tranquility Base became the cradle of our space-faring future will be remembered forever, along with the lessons of tumultuous history that got us to the Moon. These lessons will help us come together as a human community and ultimately advance forward as a species.

To allow anything else to happen would be a giant mistake.![]()

Michelle L.D. Hanlon, Professor of Air and Space Law, University of Mississippi

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.