One Chinese researcher thinks so, at least. Wu Chunfeng, head of the Tian Fu New Area Science Society, wants to use a satellite like an artificial moon, reflecting sunlight back to targeted areas of the Earth at night. The reflector would orbit above a city, providing enough illumination to replace lights on the ground with a steady glow and potentially saving on electricity costs.

Brighten the Night

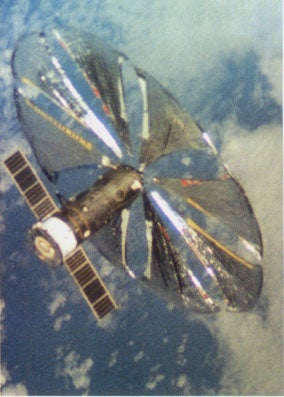

He imagines a shiny satellite unfurling in space about 300 miles above the ground and orienting itself toward cities on the ground. One would be enough to light up around 20 square miles, he says, according to China Daily, and several working in concert could brighten up to 4,000 square miles. Wu says the first should be ready to launch in 2020, and three more in 2022, though the details of the project remain largely unknown.

The plan might not be all that sound, though, according to satellite experts. Based on the scant details available, in fact, the satellite would probably never work, says Ryan Russell, an associate professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Texas at Austin.

The biggest flaw? A satellite flying low enough to deliver that much light wouldn’t be able to stay in one place.

“Their claim for 1 LEO sat at [300 miles] must be a typo or misinformed spokesperson,” Russell says in an email. “The article I read implied you could hover a satellite over a particular city, which of course is not possible.”

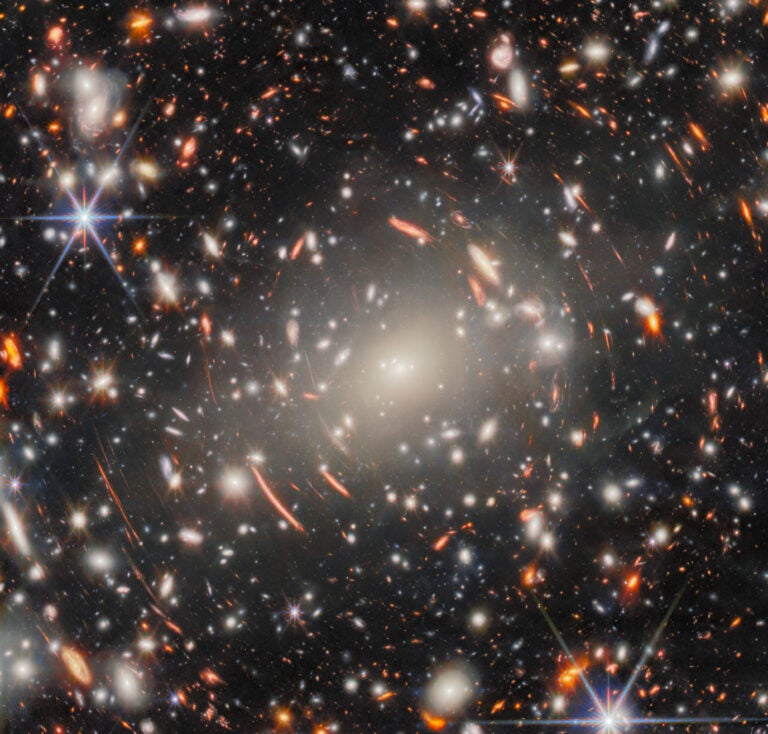

Satellites that stay over a fixed point on the Earth, what’s called a geostationary orbit, sit much further away: about 22,000 miles. At that distance, the reflective surface would need to be massive to deliver enough light for humans to see back to Earth. At a distance of just 300 miles the moon would whip around the Earth at thousands of miles per hour, beaming its light on any one place for only a fraction of a second.

You could keep an artificial moon in place with rocket thrusters, says Iain Boyd, an aerospace engineering professor at the University of Michigan, but that would eat up fuel, adding to the cost and requiring constant refueling.

A constellation of satellites circling the Earth would be necessary to keep the lights on all night, trading off reflective duties to one another as they passed by overhead. And even then, fuel is necessary to counteract the tiny atmospheric drag present even in low orbits above Earth. The International Space Station, for example, orbits at about 250 miles up and must be constantly boosted back to its orbit as it slows down due to drag.

The cost of launching and refueling multiple satellites would likely far outpace the savings on electricity, at least for the time being.

Turn Off the Lights

There’s also the question of whether we’d want a city-wide night light in the first place. Some cities across the globe are already trying to tamp down on light pollution, making their nights darker, not brighter. Excess nighttime light disrupts the activities of nocturnal animals, blocks out the stars and could even be interfering with our circadian rhythms and impacting health.

If we truly need better light solutions, it might be better to focus on more terrestrial options, Russell says.

“It’s a very complicated solution that affects everyone to a simple problem that affects a few. It’s light pollution on steroids,” he says. “And they are lighting the entire surface, while streetlights just light the streets that need to be lit. Imagine whole generations of people living in the same urban areas never seeing the stars at night?”

The artificial moon worked — briefly. As The New York Times reports, astronauts aboard the station could detect a faint beam of light arcing toward the ground, though observers on Earth saw only a momentary bright glimmer in the sky.

A second test satellite ran into problems on deployment in space, and the project was abandoned. The original plan called for a fleet of the disks, each 650 feet in diameter, to provide constant illumination to the ground, though the problem of maintaining the orbits and accurately aiming the spacecraft was never functionally addressed.

Today, when many worry that urban nights are too bright, the concept of an artificial moon seems largely unnecessary. Streetlights already provide us with adequate light, and new LED options could help cut down on electricity costs.

A night light in space may be a moonshot too far.

[Editor’s Note: Due to an error, an earlier version of this story switched the units for miles and kilometers. The numbers have been corrected.]

This article originally appeared on discovermagazine.com.