Key Takeaways:

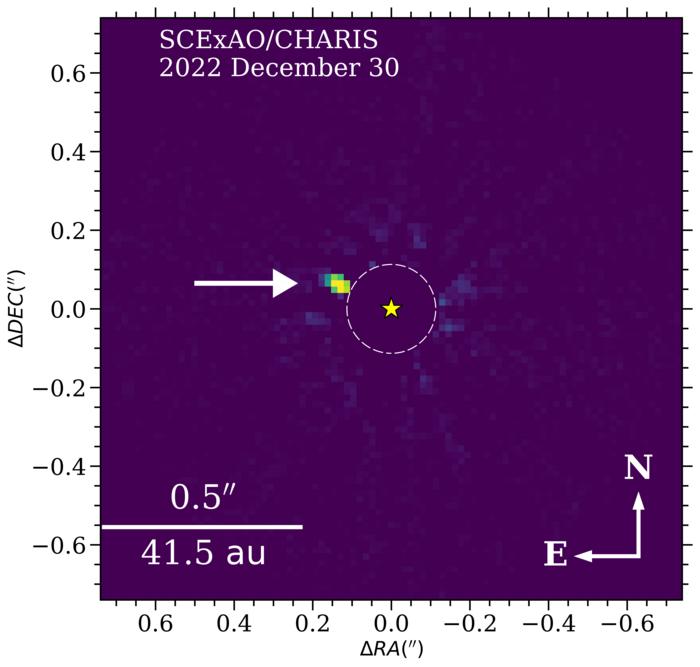

Things are cold on OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb, but to astronomers, its discovery is red hot. That’s because it is the smallest planet ever detected through gravitational microlensing, a quirk of physics that briefly makes distant objects appear brighter when a massive object passes between it and Earth.

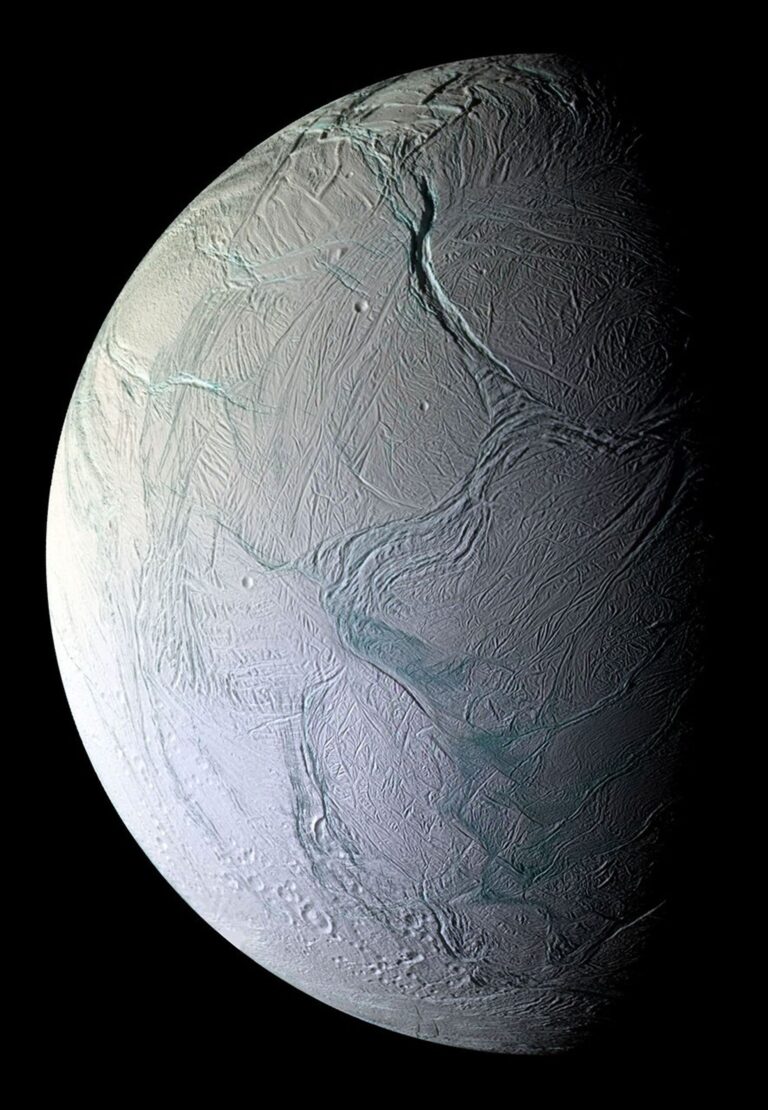

NASA made the announcement of its discovery today. (A preprint of the paper is available here.) Using data from the Spitzer Space Telescope, the team led by Ian Bond of Massey University found the Earth-size world at a distance from its parent star similar to that of Earth. Don’t pack up your bags quite yet though: the planet orbits a tiny M-dwarf star, and would be far too frigid to harbor life as we know it. Temperatures are believed to be around -400 degrees F (-240 degrees C). That makes the planet about as cold as Pluto.

Finding a separation between a planet and a star like this is also difficult. Most exoplanet searches, especially those relying on transits, rely on short period planets — those that orbit their planet in days, weeks, or months instead of years. To confirm a planet via transit, you need to witness multiple transits, so a Jupiter-distance planet would take 24 years to discover at the minimum as Jupiter has a 12-year period. Indeed, even a Mars-distance object might have only swept by the initial Kepler field twice in the first mission’s history. Around 12 percent of all discovered exoplanets have a period longer than Earth (roughly 425 planets out of 3,405 confirmed.)

But there’s another challenge: OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb is really, really far away. Think 23,400 light-years. That makes it also one of the most distant planets ever discovered. So how do we find such a small planet that far away? That brings us back to the magic of gravitational lensing.

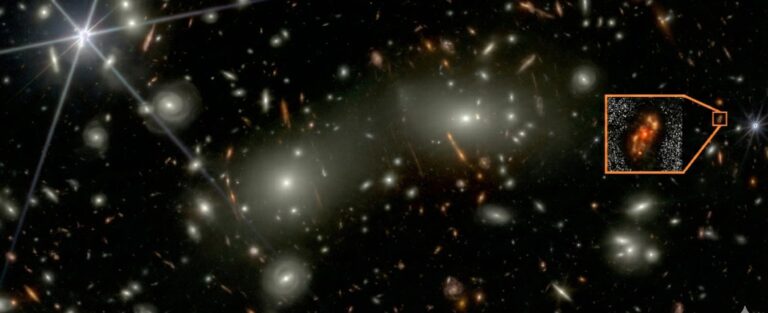

Every object in the universe sort of “presses down” on the fabric of space-time. The more massive an object, the more it makes an impression in space. This effect can be visually observed when a massive object passes in front of something else. For instance, a large star close to Earth passing in front of a small star far from Earth can reveal the distortions caused by the closer object. But this event also magnifies the more distant object from our point of view, bringing forth details we normally wouldn’t be able to see.

While some microlensing events can lead to the direct imaging of planets, this discovery still relied on a transit dimming of the parent star to observe it.

The Exoplanet Catalog lists 56 planet-like objects discovered by gravitational microlensing, most of them by the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) program that also yielded -1195Lb. The previous least-massive object known, OGLE-2005-169L b, is around the mass of Neptune. -1195Lb is estimated to be about five Earth masses, making it likely a super-Earth.

Follow-up studies may be difficult — microlensing events happen by chance. For now, we’ll just have to patiently wait to see if another star comes between us and the planet to discover anything new.