Key Takeaways:

In 1977, a group of marine researchers discovered something they’d only before theorized: cracks in the ocean floor releasing heat, warming up (and often boiling) the ocean around it. They also found mollusks in them, and subsequent vents have yielded heat resistant microbes, giant tube worms, and more fantastic creatures living in what are essentially small, underwater volcanoes.

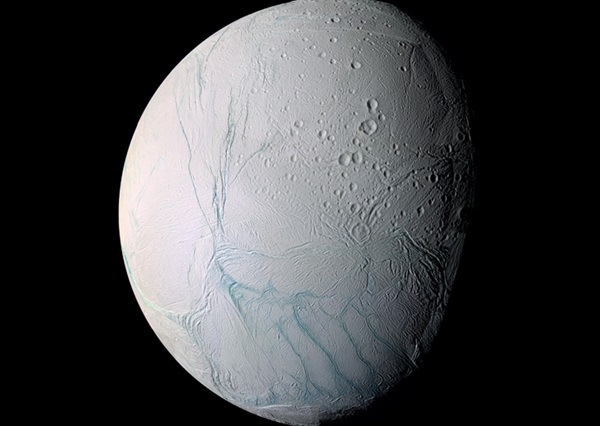

Now, NASA has announced that they have indirect evidence for hydrothermal vents beyond Earth. In its encounters with Saturn’s moon Enceladus, the Cassini craft found chemicals associated with these events. The results were published today in Science. It adds to the body of evidence that Enceladus could be ripe for life.

“Enceladus is too small to have retained the hydrogen from when it formed, so the hydrogen we see today is coming from inside Enceladus,” Linda Spilker, project scientist on the Cassini mission, said in a press conference.

Enceladus, which is a tiny moon, took Cassini researchers by surprise when they discovered what seemed to be geysers of water emitting from the south pole in 2005. Subsequent investigations built a picture of the origin: liquid water under the surface of Enceladus, which led to the idea of an entire ocean under the surface. The heating mechanism, to date, has not been discovered.

The Ion Neutral Mass Spectrometer on the craft made the observation of molecular hydrogen in the ejecta from these geysers. According to principal investigator Hunter Waite of the Southwest Research Institute and his co-investigators, the source almost certainly has to be hydrothermal vents at Enceladus’ sea floor. This means there’s plenty of geological activity, increasing the chances for life.

Indeed, researchers published a paper last year suggesting that hydrothermal vents were the source of life on Earth, where chemical reactions fed these early microbes. If that’s the case on Enceladus, the ocean may have microbial life at the very least.

“The hydrogen could be a potential source of chemical energy for any microbes living in Enceladus’ ocean,” Spilker says.

Of course, it may be years or even decades until we know for sure — in September, NASA will intentionally crash Cassini into Saturn to make sure it doesn’t crash land into Titan or Enceladus and accidentally contaminate either potentially habitable moon with Earth bacteria.