The first planets identified beyond the solar system were shockingly unlike the nine worlds long-known within it. In sorting through the new exoplanets, scientists described them in terms that compared them to Earth’s neighbors, dubbing them ‘hot Jupiters’ or ‘super-Earths’. There are also ‘hot Earths’, terrestrial worlds orbiting their suns in periods less than two days.

Although some hot Earths have neighbors, scientists have now identified a new type of system consisting only of these molten worlds.

Kepler-10b is arguably the most famous hot Earth. Discovered in 2011, it was the first Earth-sized world spotted outside the solar system. But the overheated planet has a companion, a massive giant dancing far inside what would be the orbit of Mercury in our own solar system.

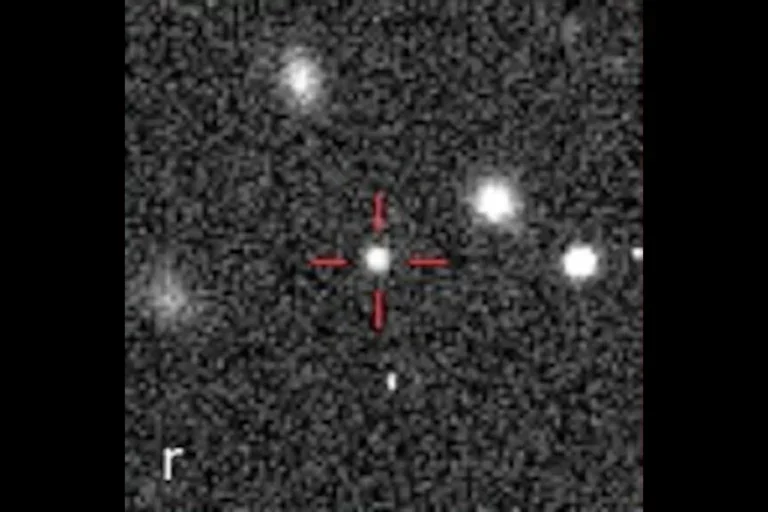

“We’ve identified a population that has an ‘isolated hot Earth,’ where the hot Earth is far from any companions,” Jason Steffen of the University of Nevada said by email. Steffen and Jeffrey Coughlin, of the SETI Institute in California, analyzed the most recent data from NASA’s Kepler spacecraft and identified the unusual isolated systems of worlds.

“A hot Earth can exist in a normal planetary system — the majority probably do,” Steffen said. “This new population has a dynamically isolated hot Earth and is therefore distinct.”

Molten Earths

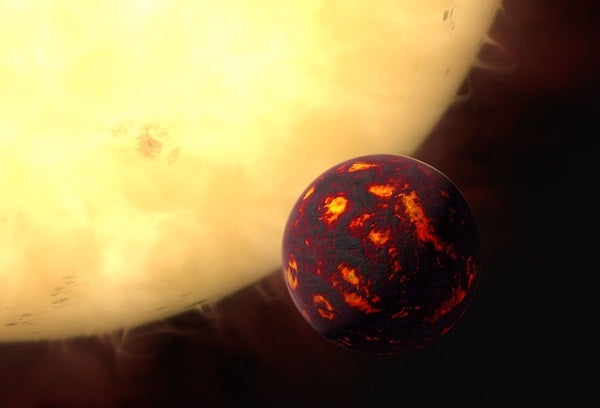

Thanks to their orbits, hot Earths get more than a little toasty. Kepler-10b, which circles its star more than 20 times closer than Mercury orbits the sun, can reach temperatures as high as 2500 degrees Farenheit (1371 degrees Celsius). Like other hot Earths, its close orbits most likely keep them with one face perpetually pointing at their star.

“If you were on the sunlit side, the surface may well be molten and slowly vaporizing due to the intense radiation from the nearby star,” Steffen said.

“On the dark side, it’s probably pretty cold since there won’t be much atmosphere to circulate the heat from the day to the night side.”

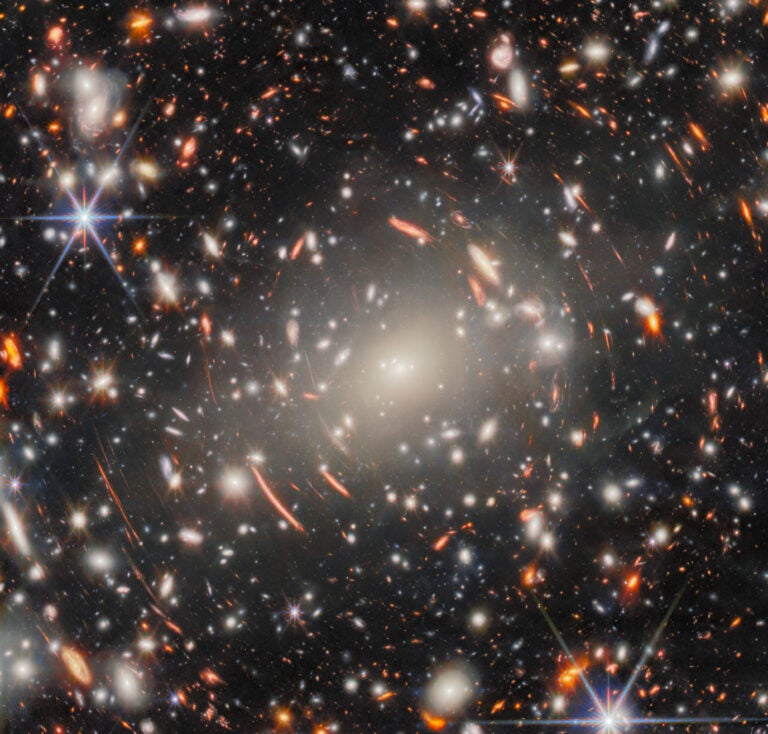

The pair examined over 3000 planets and planet candidates to investigate differences between single and multi-planet systems. Nearly two-thirds of the worlds were the only planets spotted orbiting their stars. By searching for systems that might exist in single-only systems, the pair hoped to find insights into why so many worlds danced alone.

First, though, they had to estimate how many of the one-world systems were truly single. Kepler can only spot worlds that orbit their stars along Earth’s line of sight. If the planet’s path around its sun is tilted in respect to our own, it could dance around the star unseen. Other worlds could be overlooked due to their size or distant orbits.

Out of the 144 hot Earths the team identified, they estimated that at least 24 of them orbit without another close planet, making them unique compared to multi-planet systems. Their finding suggests that at least 1 out of every 6 hot Earths have no nearby companion. In this case, ‘nearby’ means worlds with orbits “only a few times larger than the orbit of the hot Earth,” Steffen said, which would translate to one or two months.

“This might not sound like a distant orbit, but when it comes to planetary orbits, it is the ratio of the orbital period that matters,” he said. “The equivalent in our solar system would be having Mercury and Jupiter with nothing in between.”

Hot Jupiter corpses

After identifying the strange new systems, the pair turned their attention to how they could have formed. One possible source is that they are the remains of ‘hot Jupiters’, gas giants orbiting their star in only a few hours.

“A hot Jupiter could become a hot Earth if it gets sufficiently close to the star that the star pulls the atmosphere off of the planet,” Steffen said.

Gas giants in the process of losing their atmosphere have already been spotted in other systems. Previously, scientists suggested that rocky worlds several times larger than our planet known as super-Earths could be the stripped worlds, but smaller cores could be hot Earths.

Hot Jupiters are a puzzle in their own right. The first hot Jupiter was spotted in 1995, but scientists still aren’t sure how they form. Most likely, they formed in the distant, cooler regions of their system and migrated inwards, knocking other planets out of the way before something halted their progress and they settled into a close orbit around their star. Only a handful of the hot giants have other planets in their systems.

If hot Earths are the cores of hot Jupiters, then the overbaked gas giants could be twice as common as previously estimated, Steffen said. That could affect understanding of how these oddball worlds form.

Another option, proposed for Kepler-10, is that the smaller terrestrial worlds began their migration before their companions formed. Ultimately, the traveling rocky world is stopped by the disk of gas and dust from which it formed.

Finally, interactions between planets in a system could drive smaller rocky worlds inward. Some worlds are booted out of the system, and the hot Earth settles into orbit around its sun.

The ongoing Kepler extended mission (K2) and the upcoming Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) mission should both discover more hot Earths, Steffen said. Most of Kepler’s stars are dim, so the mission’s sample only has a few systems that allow other techniques to hunt for distant planets.

“The advantage that K2 and TESS bring is that they will find hot Earths orbiting much brighter stars,” he said.

The brighter stars will make it easier to detect more distant companions.

“Then we can determine the relative frequency of nearby versus distant versus nonexistent planetary companions to hot Earths,” Steffen said.