Most dwarf planets and solar system bodies similar to Ceres’ size possess many large impact craters from billions of years of being bashed into by other space debris during the formation of the solar system. But one place where this isn’t the case? Ceres, the largest object in a field full of formation debris.

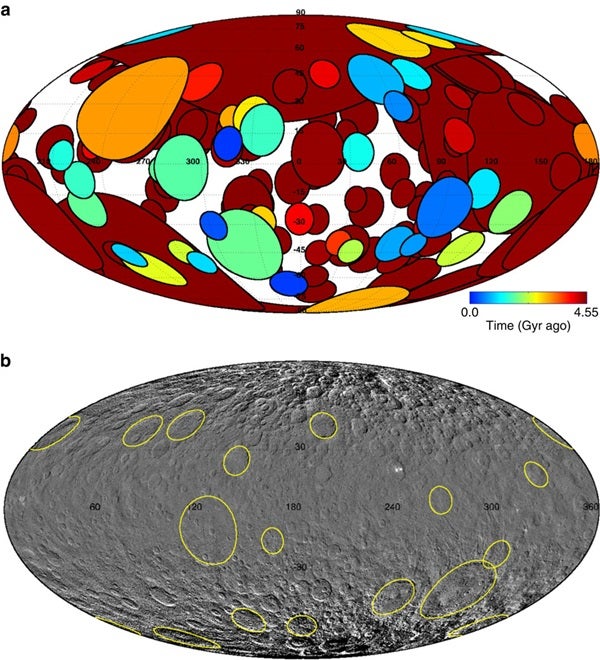

In a new study published in Nature Communications, a team of researchers from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) found that Ceres lacks the size and distribution of large craters that the researchers were expecting to see on the surface.

The collision models predicted that Ceres should have accumulated anywhere from 10 to 15 craters around 250 miles (400km) wide, and at least 40 craters around 162 miles (100km) wide. Using NASA’s Dawn spacecraft, the team only found evidence of 16 craters wider than 100 kilometers and no craters larger than 175 miles (280km) wide.

Ceres was believed to have formed nearly 4.5 billion years ago when our solar system was just beginning to form. It grew into the size it is today through collisions of smaller objects that became gravitationally bound to each other.

“The leading theory is that Ceres, as well as main belt asteroids, formed in situ,” says Simone Marchi, a SwRI senior researcher with an interest in asteroids and terrestrial planets. “They are leftovers of the accretion of planets.”

When using Dawn’s global topography data, Marchi and his team found a plethora of smaller impact craters, but the largest crater was still only 280 km in diameter. Ceres defied most crater size and distribution models and is very different from images of other asteroids.

Researchers think that the craters could have been abolished slowly over the years as a deep subsurface ice-rich layer of material provoked the crater rims to relax rendering the craters unseeable. It is also possible that cryolava may have flowed at one point over the surface, but may have not been very efficient on the large and deepest impact craters.

When Dawn imaged the smaller asteroid Vesta, which is about half the size of Ceres, it acquired huge craters, which included one about 500 kilometers (300 miles) wide and covered almost one entire side on Vesta.

“The smaller asteroid Vesta (first target of the Dawn mission) has 2 craters greater than 400 km,” says Marchi. “Extrapolating from this, Ceres should have at least six or seven, or more likely greater than 10 craters larger than 400 km. Instead, it has none.”

Marchi says it is without a doubt that Ceres acquired these large craters at one point in its life. It is very likely that these craters were all but obliterated from recognition over geological time scale. But a closer look at Ceres, researchers found a possible solution to this problem of missing craters.

“As a matter of fact, we do see a very large (800 km wide) depression that might be a relict impact structure,” says Marchi. “This would be compatible with what is expected from modeling.”

The next step for Marchi and his team is to look for the process that was responsible for obliterating these large craters from the surface of Ceres. If this process is possible on Ceres, it very well may have happened on other asteroids or dwarf planets. This research may unearth a new type of internal evolution within these celestial bodies.