Before the recent University of British Columbia graduate has even entered grad school — let alone had time to breathe after her undergrad — she already has four planetary discoveries under her belt.

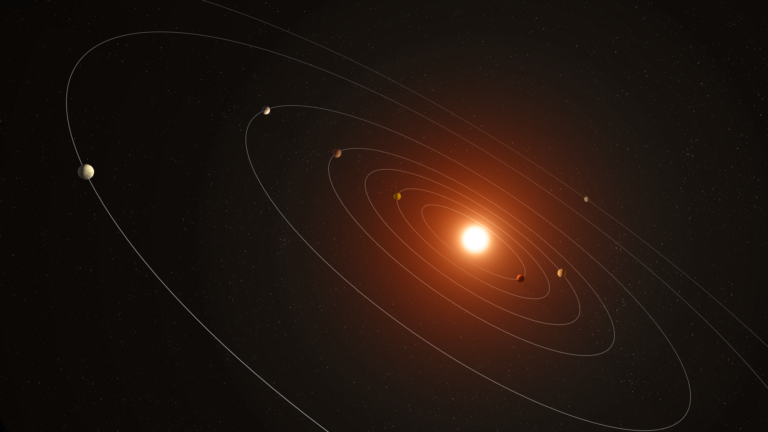

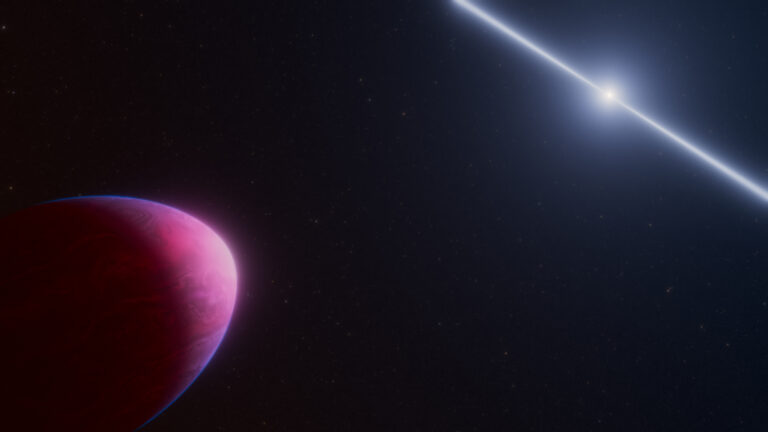

And what a remarkably varied quartet of worlds she found. There’s the Mercury-sized planet, one of the smallest discovered in the Kepler dataset. There are two super-Earths, though likely not habitable. Then there’s the warm Neptune. It’s the one right in the habitable zone. Though likely a gas giant, it could have lush moons ripe for life.

All of the planets were figurative needles-in-the-haystack, part of why NASA and other Kepler researchers may have passed them over. She was looking for weak signals, and that included the warm Neptune, which has a 637 earth-day year.

“It’s got such a long period that only two transits were visible out of the four years of data,” Kunimoto said.

As for the Mercury-sized world? The transit was so faint that few might have given it a second glance.

“It’s actually in the regime of signals that NASA wouldn’t have even looked at,” Kunimoto said.

In the end, its short period won out, displaying a repeating signal over the duration of the mission.

“They were all several hours in duration, and they had roughly the same depths each time,” she said.

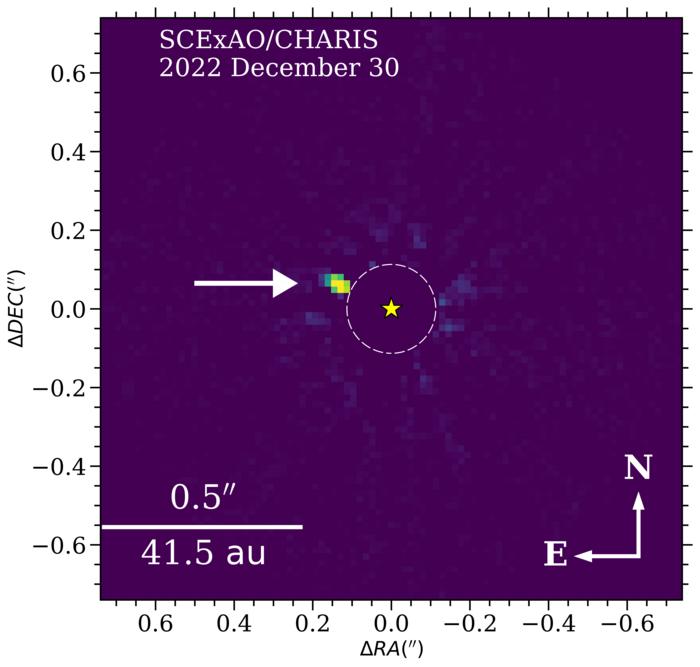

To find the four planets, Kunimoto took 400 light curves from Kepler data. Applying a higher threshold for transit signals, she winnowed a list of previously discovered planets and false positives down about 26 new candidates.

“Most of them were found in stars that had high stellar rotation, so that was most likely the cause for false positives,” she says.

Her process speaks to a newer trend in astronomy: the use of archival data to draw out new discoveries. Kepler’s data set is openly available, and a site called PlanetHunters.org even allows the public to help find transits of planets across the light of their home stars.

Jaymie Matthews, Kunimoto’s advisor, says that the days of archives conjuring images of dusty old books are gone.

“Data mining has become another way to strike scientific gold,” he says. “Also, with the passage of time, new analysis techniques appear which can revitalize an old data set, especially when the original investigators of those data have gone on to other objectives.”

Kunimoto and Matthews first began working together shortly after she took a course from him on exoplanets, piquing her interest and leading to an independent study course. Matthews taught Kunimoto how to work with the Kepler data and set up some time at NASA Ames to delve deeper.

From there, it was a matter of figuring out a way to find more planets out of the dataset.

“The uniqueness of this study was extending the search to slightly lower signal-to-noise levels, and that an undergraduate student was able to master the techniques and the careful judgment and intuition to conduct this search on 400 light curves in a matter of months,” Matthews said.

The end results are in the peer-review process at The Astronomical Journal. Kunimoto is preparing to go to grad school at UCB in the fall, where she’ll continue studying exoplanets. She says she’s likely done with the Kepler datasets, instead opting study mass-radius relations in exoplanets for her master’s degree.

But in the meantime, she goes into grad school with something few of her peers can claim: she’s discovered four planets before her career has officially begun. And there’s plenty more in store.