The team detected the galaxy as it was 13 billion years ago, or when the universe was a toddler on a cosmic time scale.

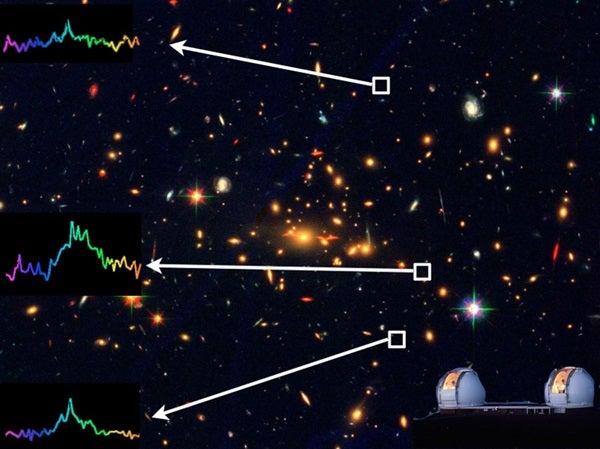

The detection was made using the DEIMOS instrument fitted on the ten-meter Keck II telescope, and was made possible through a phenomenon predicted by Einstein in which an object is magnified by the gravity of another object that is between it and the viewer. In this case, the detected galaxy was behind the galaxy cluster MACS2129.4-0741, which is massive enough to create three different images of the object.

“If the light from this galaxy was not magnified by factors of 11, five and two, we would not have been able to see it,” said Kuang-Han Huang from UC Davis. “It lies near the end of the reionization epoch, during which most of the hydrogen gas between galaxies transitioned from being mostly neutral to being mostly ionized — and lit up the stars for the first time). That shows how gravitational lensing is important for understanding the faint galaxy population that dominates the reionization photon production.”

The galaxy’s magnified images were originally seen separately in both Keck Observatory and Hubble Space Telescope data. The team collected and combined all the Keck Observatory/DEIMOS spectra from all three images, confirming they were the same and that this is a triply-lensed system.

“We now have good constraints on when the reionization process ends — at redshift around 6 or 12.5 billion years ago — but we don’t yet know a lot of details about how it happened,” Huang said. “The galaxy detected in our work is likely a member of the faint galaxy population that drives the reionization process.”

“This galaxy is exciting because the team infers a very low stellar mass, or only one percent of one percent of the Milky Way Galaxy,” Kassis said. “It’s a very, very small galaxy, and at such a great distance, it’s a clue in answering one of the fundamental questions astronomy is trying to understand: What is causing the hydrogen gas at the very beginning of the universe to go from neutral to ionized about 13 billion years ago? That’s when stars turned on and matter became more complex.”