Key Takeaways:

The discovery may offer a glimpse into the life story of the universe’s great beacons.

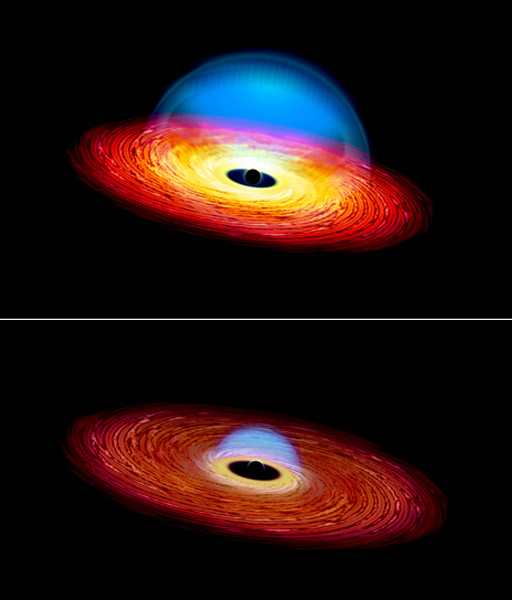

Quasars are massive, luminous objects that draw their energy from black holes. Until now, scientists have been unable to study both the bright and dim phases of a quasar in a single source.

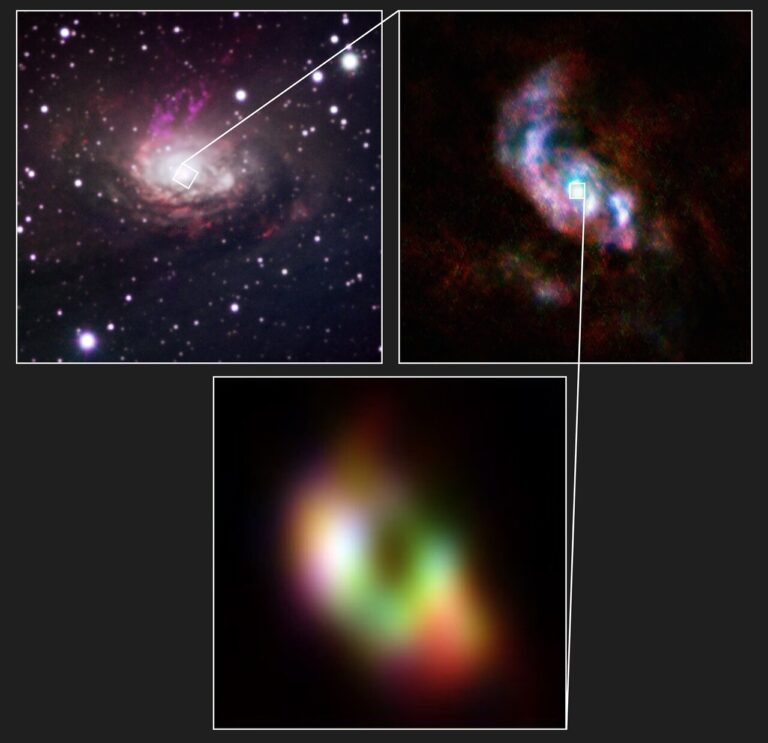

Yale-led researchers spotted a quasar that had dimmed by a factor of six or seven, compared with observations from a few years earlier.

“We’ve looked at hundreds of thousands of quasars at this point, and now we’ve found one that has switched off,” said C. Megan Urry from Yale. “This may tell us something about their lifetimes.”

Stephanie LaMassa, also from Yale, noticed the phenomenon during an ongoing probe of Stripe 82 — a sliver of the sky found along the celestial equator. Stripe 82 has been scanned in numerous astronomical surveys, including the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

“This is like a dimmer switch,” LaMassa said. “The power source just went dim. Because the life cycle of a quasar is one of the big unknowns, catching one as it changes, within a human lifetime, is amazing.”

Even more significant for astronomers was the weakening of the quasar’s broad emission lines. Visible on the optical spectrum, these broad emission lines are signatures of gas that are too distant to be consumed by a black hole, yet close enough to be “excited” by energy from material that does fall into a black hole.

The change in the emission lines is what told researchers that the black hole had essentially gone on a diet and was giving off less energy as a result. That’s when the “changing look” quasar hit its dimmer switch, and most of its broad emission lines disappeared.

The Yale team analyzed a variety of observation data, including recent optical spectra information and archival optical photometry and X-ray spectra information. They needed to rule out the possibility the quasar merely appeared to lose brightness due to a gas cloud or other object passing in front of it.

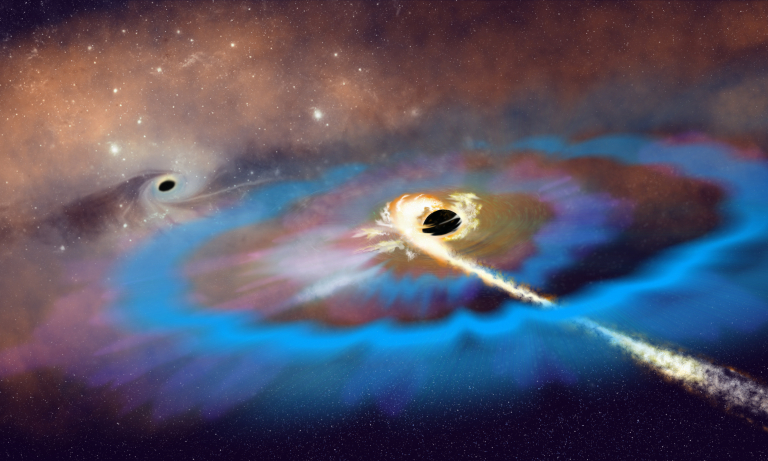

The findings may prove invaluable on several fronts. First, they provide direct information about the intermittent nature of quasar activity; even more intriguingly, they hint at the sporadic activity of black holes.

“It makes a difference to know how black holes grow,” Urry said, noting that all galaxies have black holes, and quasars are a phase that black holes go through before becoming dormant. “This perhaps has implications for how the Milky Way looks today.”

Additionally, there is the chance the quasar may fire up again, showing astronomers yet another changing look.

“Even though astronomers have been studying quasars for more than 50 years, it’s exciting that someone like me, who has studied black holes for almost a decade, can find something completely new,” LaMassa said.