The unique findings illustrate a new dimension to galaxy evolution and came courtesy of the European Space Agency’s Herschel space observatory, in which NASA played a key role, and NASA’s Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes.

Astronomers want to understand why galaxies in the local universe fall into two major categories: younger, star-forming spirals — like our Milky Way — and older ellipticals, in which fresh star-making has ceased. The new study’s galaxy, NGC 3226, occupies a transitional middle ground, so getting a bead on its star formation is critical.

“We have explored the fantastic potential of big data archives from NASA’s Hubble, Spitzer, and ESA’s Herschel observatory to pull together a picture of an elliptical galaxy that has undergone huge changes in its recent past due to violent collisions with its neighbors,” said Philip Appleton from the NASA Herschel Science Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “These collisions are modifying not only its structure and color, but also the condition of the gas that resides in it, making it hard at the moment for the galaxy to form many stars.”

NGC 3226 is relatively close, just 50 million light-years away. Several star-studded, gassy loops emanate from NGC 3226. Filaments also run out from it and between a companion galaxy, NGC 3227. These streamers of material suggest that a third galaxy probably existed there until recently — that is, until NGC 3226 cannibalized it, strewing pieces of the shredded galaxy all over the area.

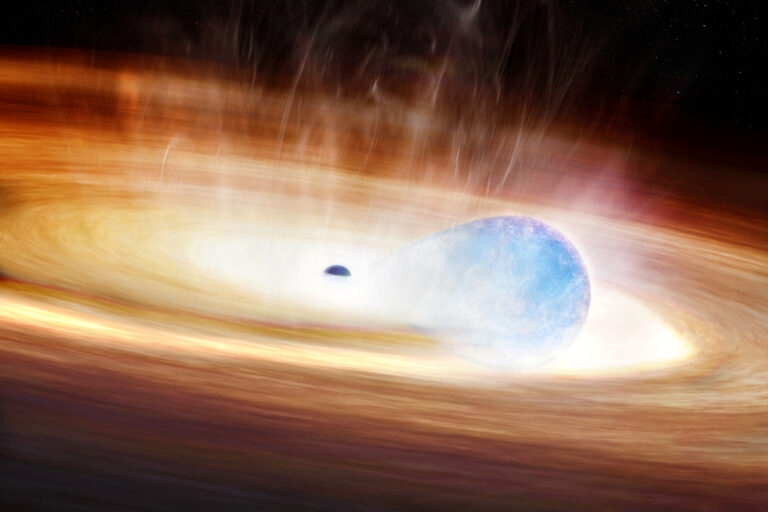

A prominent piece of these messy leftovers stretches 100,000 light-years and extends right into the core of NGC 3226. This long tail ends as a curved plume in a disk of warm hydrogen gas and a ring of dust. Contents of the tail, thought to be the debris from that departed galaxy, are falling into NGC 3226, drawn by its gravity.

In many instances, adding material to galaxies in this manner rejuvenates them, triggering new rounds of star birth thanks to gas and dust gelling together. Yet data from the three telescopes agree that NGC 3226 has a low rate of star formation. It appears that in this case, the material falling into NGC 3226 is heating up as it collides with other galactic gas and dust, quenching star formation instead of fueling it.

The outcome could have been different, as NGC 3226 hosts a supermassive black hole at its center. The influx of gas and dust might have ended up just feeding the black hole, setting off energetic outpourings as the material crashed together while whirling toward its doom. Instead, the black hole in NGC 3226’s core is just snacking, not gorging, as the material has spread out in the galaxy’s central regions.

“We are discovering that gas does not simply funnel down into the center of a galaxy and feed the supermassive black hole known to be lurking there,” Appleton said. “Rather, it gets hung up in a warm disk, shutting down star formation and probably frustrating the black hole’s growth by being too turbulent at this point in time.”

NGC 3226 is considered something between a youthful “blue” galaxy and an old “red” galaxy. The colors refer to the predominantly galactic blue light radiated by giant young stars — a telltale sign of recent star formation — and the reddish light cast by mature stars in the absence of new blue ones.

This intermediary galaxy illuminates how galaxies accruing fresh gas and dust can bloom with new stars or have their stellar factories close shop, at least temporarily. After all, as the warm gas flooding NGC 3226 cools to star-forming temperatures, the galaxy should get a second wind.

Intriguingly, ultraviolet and optical-light observations suggest that NGC 3226 may have produced more stars in the past, leading to its current intermediate color, somewhere between red and blue. The new study indicates that those traces of youth must indeed be lingering from higher levels of star formation, before the infalling gas scrambled the scene.

“NGC 3226 will continue to evolve and may hatch abundant new stars in the future,” said Appleton. “We’re learning that the transition from young- to old-looking galaxies is not a one-way, but a two-way street.”