Key Takeaways:

“Our model indicates that this vast shell of gas and dust has a more complex origin than is generally assumed,” said Thomas Madura from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “For the first time, we see evidence suggesting that intense interactions between the stars in the central binary played a significant role in sculpting the nebula we see today.”

Eta Carinae lies about 7,500 light-years away in the southern constellation Carina and is one of the most massive binary systems astronomers can study in detail. The smaller star is about 30 times the mass of the Sun and may be as much as a million times more luminous. The primary star contains about 90 solar masses and emits 5 million times the Sun’s energy output. Both stars are fated to end their lives in spectacular supernova explosions.

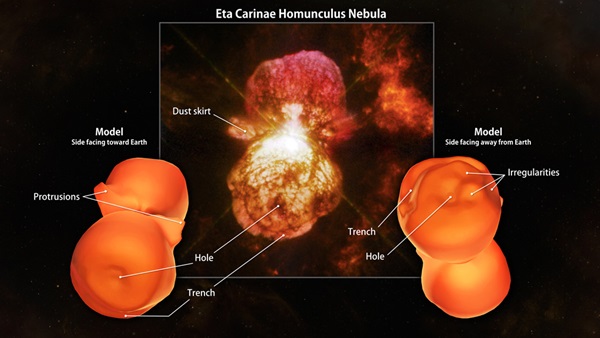

Between 1838 and 1845, Eta Carinae underwent a period of unusual variability during which it briefly outshone Canopus, normally the second-brightest star. As a part of this event, which astronomers call the Great Eruption, a gaseous shell containing at least 10 and perhaps as much as 40 times the Sun’s mass was shot into space. This material forms a twin-lobed dust-filled cloud known as the Homunculus Nebula, which is now about a light-year long and continues to expand at more than 1.3 million mph (2.1 million km/h).

Using the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope (VLT) and its X-Shooter spectrograph over two nights in March 2012, the team imaged near-infrared, visible, and ultraviolet wavelengths along 92 separate swaths across the nebula, making the most complete spectral map to date. The researchers have used the spatial and velocity information provided by this data to create the first high-resolution, fully 3-D model of the Homunculus Nebula. The new model contains none of the assumptions about the cloud’s symmetry found in previous studies.

The shape model was developed using only a single emission line of near-infrared light emitted by molecular hydrogen gas. The characteristic 2.12-micron light shifts in wavelength slightly depending on the speed and direction of the expanding gas, allowing the team to probe even dust-obscured portions of the Homunculus that face away from Earth.

“Our next step was to process all of this using 3-D modeling software I developed in collaboration with Nico Koning from the University of Calgary in Canada,” said Wolfgang Steffen from the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “The program is simply called ‘Shape,’ and it analyzes and models the 3-D motions and structure of nebulae in a way that can be compared directly with observations.”

The new shape model confirms several features identified by previous studies, including pronounced holes located at the ends of each lobe and the absence of any extended molecular hydrogen emission from a dust skirt apparent in visible light near the center of the nebula. New features include curious arm-like protrusions emanating from each lobe near the dust skirt; vast, deep trenches curving along each lobe; and irregular divots on the side facing away from Earth.

“One of the questions we set out to answer with this study is whether the Homunculus contains any imprint of the star’s binary nature, since previous efforts to explain its shape have assumed that both lobes were more or less identical and symmetric around their long axis,” said Jose Groh from Geneva University in Switzerland. “The new features strongly suggest that interactions between Eta Carinae’s stars helped mold the Homunculus.”

Every 5.5 years, when their orbits carry them to their closest approach, called periastron, the immense and brilliant stars of Eta Carinae are only as far apart as the average distance between Mars and the Sun. Both stars possess powerful gaseous outflows called stellar winds, which constantly interact but do so most dramatically during periastron, when the faster wind from the smaller star carves a tunnel through the denser wind of its companion. The opening angle of this cavity closely matches the length of the trenches (130°) and the angle between the arm-like protrusions (110°), indicating that the Homunculus likely continues to carry an impression from a periastron interaction around the time of the Great Eruption.

Once the researchers had developed their Homunculus model, they took things one step further. They converted it to a format that can be used by 3-D printers.

“Now anyone with access to a 3-D printer can produce his own version of this incredible object,” said Theodore Gull from Goddard Space Flight Center. “While 3-D-printed models will make a terrific visualization tool for anyone interested in astronomy, I see them as particularly valuable for the blind, who now will be able to compare embossed astronomical images with a scientifically accurate representation of the real thing.”