On December 11, 2010, Steve Larson of the Catalina Sky Survey noticed an odd brightness from Scheila, an asteroid on the outer region of the main belt of asteroids that orbit in an area between Mars and Jupiter. Three streams of dust appeared to trail from the asteroid. Data from NASA’s Swift Satellite and the Hubble Space Telescope suggested that a smaller asteroid’s impact was the likely trigger for the appearance of comet-like tails from Scheila. However, questions remained about the date when the dust emission occurred and how the triple dust tails formed. The current research team sought answers to these queries.

The top of Figure 1 shows images of the development of the dust tails taken by the Murikabushi Telescope on the 12th and 19th of December 2010. Although asteroids generally look like points when observed from Earth, Scheila looked like a comet. As the three streaks of dust streamed from the asteroid, their surface brightness decreased. Eventually, the dust clouds became undetectable, and then a faint linear structure appeared. The bottom of Figure 1 shows the image obtained by the Subaru Telescope on March 2, 2011.

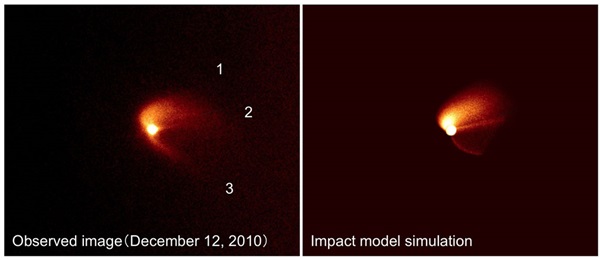

To explain the formation of Scheila’s triple dust tails, the research team conducted a computer simulation of Scheila’s dust emission on December 3. Their simulation was based on information gained through impact experiments in a laboratory at ISAS, a hypervelocity impact facility and division of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

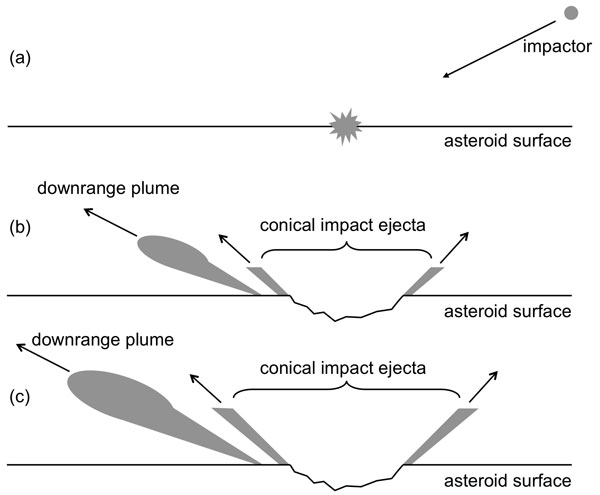

Figure 2 shows the ejecta produced by an oblique impact, which was not a head-on collision. Two prominent features characterize oblique impacts and the shock waves generated by them. One feature, a downrange plume, occurs in a direction downrange from the impact site and results from the fragmentation or sometimes evaporation of the object that impacted another. A second feature occurs during the physical destruction of the impacted object; a shock wave spreads from the impact site, scoops out materials (conical impact ejecta), and forms an impact crater. The axis of the cone of ejecta is roughly perpendicular to the surface at the impact site.

Taking all of the evidence into account — their observations and simulations — the research team concluded that there is only one way to explain the mysterious brightness and triple tails of dust from Scheila. A smaller asteroid obliquely impacted Scheila from behind.