The findings provide weighty new evidence that the gold, platinum, palladium, and other iron-loving elements found in the crusts and mantles of Earth, the Moon, and Mars arrived on mini-planet-sized impactors during the final phase of planet formation in our solar system. These massive collisions occurred within tens of millions of years of the even bigger impact that produced our Moon, say the researchers from the University of Maryland, College Park, the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, California.

“Our understanding of the formation of Earth and other planets with iron cores and silicate mantles suggests that iron-loving elements are pulled into the planet cores as they form,” said Richard Walker, geology professor from the University of Maryland. “Thus, we should have an Earth that essentially has no gold or other iron-loving metal ores in its crust for us to mine.”

The fact that we do, Walker said, has long suggested that something must have happened to bring new iron-loving elements to Earth after completion of the separation of the metallic core and silicate mantle. What scientists didn’t know until now was whether this late accretion of material occurred in big chunks over a relatively short period of time or as a ‘rain’ of smaller pieces of material over a longer time.

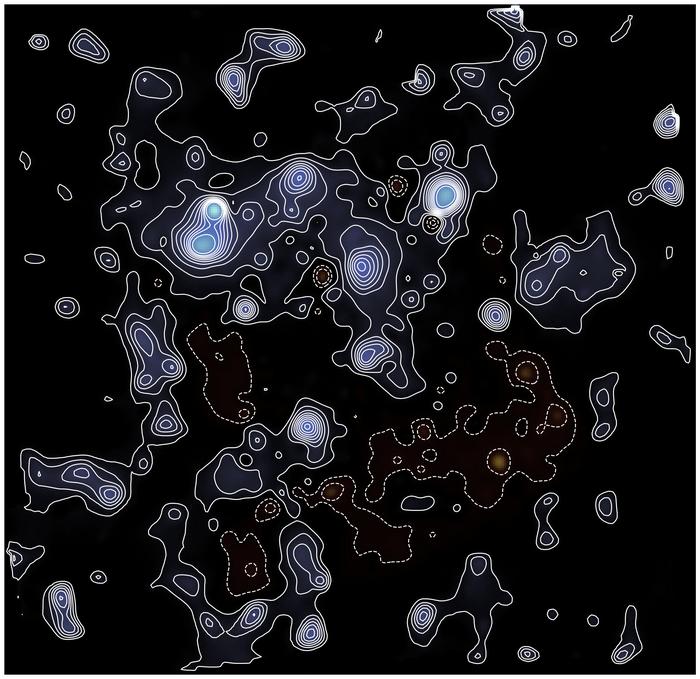

To determine the answer, Walker and colleagues James Day of the University of Maryland and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, William Bottke and David Nesvorny from the Southwest Research Institute, and Linda Elkins-Tanton from MIT, used numerical models to see what size objects would best match the needed criteria.

These criteria included (1) providing the right amount of iron-loving metals to Earth, the Moon, and Mars; (2) being large enough to breach the crusts and mantles of these bodies, creating local molten rock ponds from their impact energy and efficiently mixing into the mantle; and (3) not being so large as to cause a fragmenting and reformation of the planet cores. The latter would have resulted in most of the newly added iron-loving elements being pulled down into the cores, as well.

The researchers showed that they could best reproduce these results if the late accretion population was dominated by a limited number of massive projectiles. Their results indicate the largest Earth impactor was 1,500 to 2,000 miles (2,400 to 3,200 kilometers) in diameter, roughly the size of Pluto, while those hitting the Moon were only 150 to 200 miles (250 to 300 km) across.

“These impactors are thought to be large enough to produce the observed enrichments in highly siderophile (iron-loving) elements, but not so large that their fragmented cores joined with the planet’s core,” said Bottke.

The team also reports that their predicted projectile sizes also are consistent with physical evidence such as the size distributions of today’s asteroids and of ancient martian impact scars.

The findings provide weighty new evidence that the gold, platinum, palladium, and other iron-loving elements found in the crusts and mantles of Earth, the Moon, and Mars arrived on mini-planet-sized impactors during the final phase of planet formation in our solar system. These massive collisions occurred within tens of millions of years of the even bigger impact that produced our Moon, say the researchers from the University of Maryland, College Park, the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, California.

“Our understanding of the formation of Earth and other planets with iron cores and silicate mantles suggests that iron-loving elements are pulled into the planet cores as they form,” said Richard Walker, geology professor from the University of Maryland. “Thus, we should have an Earth that essentially has no gold or other iron-loving metal ores in its crust for us to mine.”

The fact that we do, Walker said, has long suggested that something must have happened to bring new iron-loving elements to Earth after completion of the separation of the metallic core and silicate mantle. What scientists didn’t know until now was whether this late accretion of material occurred in big chunks over a relatively short period of time or as a ‘rain’ of smaller pieces of material over a longer time.

To determine the answer, Walker and colleagues James Day of the University of Maryland and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, William Bottke and David Nesvorny from the Southwest Research Institute, and Linda Elkins-Tanton from MIT, used numerical models to see what size objects would best match the needed criteria.

These criteria included (1) providing the right amount of iron-loving metals to Earth, the Moon, and Mars; (2) being large enough to breach the crusts and mantles of these bodies, creating local molten rock ponds from their impact energy and efficiently mixing into the mantle; and (3) not being so large as to cause a fragmenting and reformation of the planet cores. The latter would have resulted in most of the newly added iron-loving elements being pulled down into the cores, as well.

The researchers showed that they could best reproduce these results if the late accretion population was dominated by a limited number of massive projectiles. Their results indicate the largest Earth impactor was 1,500 to 2,000 miles (2,400 to 3,200 kilometers) in diameter, roughly the size of Pluto, while those hitting the Moon were only 150 to 200 miles (250 to 300 km) across.

“These impactors are thought to be large enough to produce the observed enrichments in highly siderophile (iron-loving) elements, but not so large that their fragmented cores joined with the planet’s core,” said Bottke.

The team also reports that their predicted projectile sizes also are consistent with physical evidence such as the size distributions of today’s asteroids and of ancient martian impact scars.