The magnetic field strength is 25 Gauss, or 50 times stronger than the magnetic field at the surface that makes compass needles align north-south. Although geophysicists predict this number is in the middle of the range, it puts constraints on the identity of the heat sources in the core that keep the internal dynamo running to maintain this magnetic field.

“This is the first really good number we’ve had based on observations, not inference,” said Bruce A. Buffett from University of California, Berkeley. “The result is not controversial, but it does rule out a very weak magnetic field and argues against a very strong field.”

A strong magnetic field inside the outer core means there is a lot of convection and a lot of heat being produced, which scientists would need to account for, Buffett said. The presumed sources of energy are the residual heat from 4 billion years ago when the planet was hot and molten, the release of gravitational energy as heavy elements sink to the bottom of the liquid core, and the radioactive decay of long-lived elements such as potassium, uranium, and thorium.

A weak field — 5 Gauss, for example — would imply that little heat is being supplied by radioactive decay, while a strong field, on the order of 100 Gauss, would imply a large contribution from radioactive decay.

“A measurement of the magnetic field tells us what the energy requirements are and what the sources of heat are,” Buffett said.

About 60 percent of the power generated inside Earth likely comes from the exclusion of light elements from the solid inner core as it freezes and grows, he said. This constantly builds up crud in the outer core.

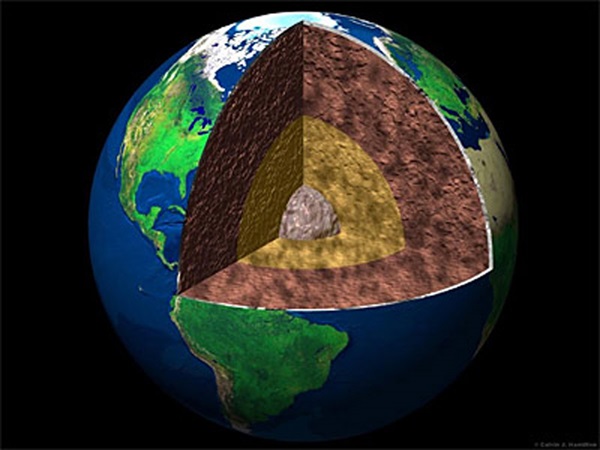

The Earth’s magnetic field is produced in the outer two-thirds of the planet’s iron/nickel core. This outer core, about 1,400 miles (2,300 km) thick, is liquid, while the inner core is a frozen iron and nickel wrecking ball with a radius of about 800 miles (1,300 km) — roughly the size of the Moon. A hot, gooey mantle and a rigid surface crust surround the core.

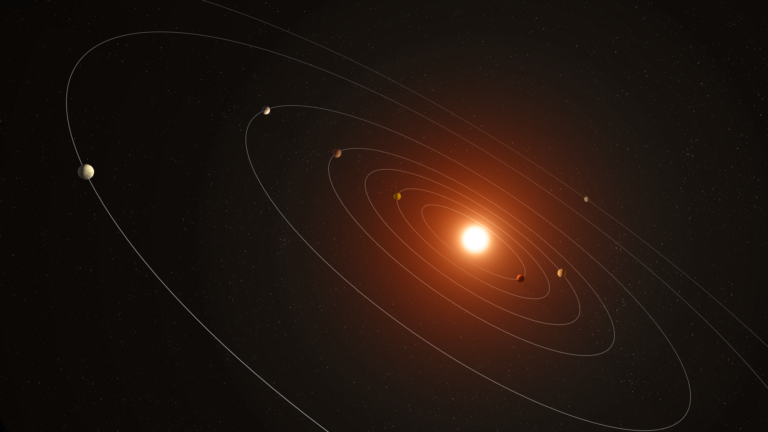

The cooling Earth originally captured its magnetic field from the planetary disk in which the solar system formed. That field would have disappeared within 10,000 years if not for the planet’s internal dynamo, which regenerates the field thanks to heat produced inside the planet. The heat makes the liquid outer core boil, or “convect,” and as the conducting metals rise and then sink through the existing magnetic field, they create electrical currents that maintain the magnetic field. This roiling dynamo produces a slowly shifting magnetic field at the surface.

“You get changes in the surface magnetic field that look a lot like gyres and flows in the oceans and the atmosphere, but these are being driven by fluid flow in the outer core,” Buffett said.

Buffett is a theoretician who uses observations to improve computer models of Earth’s internal dynamo. Now at work on a second-generation model, he admits that a lack of information about conditions in the Earth’s interior has been a big hindrance to making accurate models.

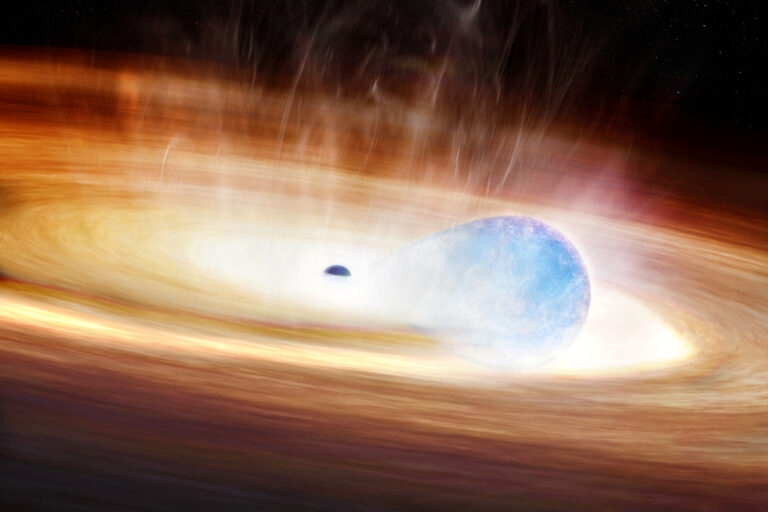

He realized, however, that the tug of the Moon on the tilt of Earth’s spin axis could provide information about the magnetic field inside. This tug would make the inner core precess — that is, make the spin axis slowly rotate in the opposite direction — which would produce magnetic changes in the outer core that damp the precession. Radio observations of distant quasars — extremely bright, active galaxies — provide precise measurements of the changes in Earth’s rotation axis needed to calculate this damping.

“The Moon is continually forcing the rotation axis of the core to precess, and we’re looking at the response of the fluid outer core to the precession of the inner core,” he said.

By calculating the effect of the Moon on the spinning inner core, Buffett discovered that the precession makes the slightly out-of-round inner core generate shear waves in the liquid outer core. These waves of molten iron and nickel move within a tight cone only 100 to 130 feet (30 to 40 meters) thick, interacting with the magnetic field to produce an electric current that heats the liquid. This serves to damp the precession of the rotation axis. The damping causes the precession to lag behind the Moon as it orbits Earth. A measurement of the lag allowed Buffett to calculate the magnitude of the damping, and the magnetic field inside the outer core.

Buffett noted that the calculated field — 25 Gauss — is an average over the entire outer core. The field is expected to vary with position.

“I still find it remarkable that we can look to distant quasars to get insights into the deep interior of our planet,” Buffett said.

The magnetic field strength is 25 Gauss, or 50 times stronger than the magnetic field at the surface that makes compass needles align north-south. Although geophysicists predict this number is in the middle of the range, it puts constraints on the identity of the heat sources in the core that keep the internal dynamo running to maintain this magnetic field.

“This is the first really good number we’ve had based on observations, not inference,” said Bruce A. Buffett from University of California, Berkeley. “The result is not controversial, but it does rule out a very weak magnetic field and argues against a very strong field.”

A strong magnetic field inside the outer core means there is a lot of convection and a lot of heat being produced, which scientists would need to account for, Buffett said. The presumed sources of energy are the residual heat from 4 billion years ago when the planet was hot and molten, the release of gravitational energy as heavy elements sink to the bottom of the liquid core, and the radioactive decay of long-lived elements such as potassium, uranium, and thorium.

A weak field — 5 Gauss, for example — would imply that little heat is being supplied by radioactive decay, while a strong field, on the order of 100 Gauss, would imply a large contribution from radioactive decay.

“A measurement of the magnetic field tells us what the energy requirements are and what the sources of heat are,” Buffett said.

About 60 percent of the power generated inside Earth likely comes from the exclusion of light elements from the solid inner core as it freezes and grows, he said. This constantly builds up crud in the outer core.

The Earth’s magnetic field is produced in the outer two-thirds of the planet’s iron/nickel core. This outer core, about 1,400 miles (2,300 km) thick, is liquid, while the inner core is a frozen iron and nickel wrecking ball with a radius of about 800 miles (1,300 km) — roughly the size of the Moon. A hot, gooey mantle and a rigid surface crust surround the core.

The cooling Earth originally captured its magnetic field from the planetary disk in which the solar system formed. That field would have disappeared within 10,000 years if not for the planet’s internal dynamo, which regenerates the field thanks to heat produced inside the planet. The heat makes the liquid outer core boil, or “convect,” and as the conducting metals rise and then sink through the existing magnetic field, they create electrical currents that maintain the magnetic field. This roiling dynamo produces a slowly shifting magnetic field at the surface.

“You get changes in the surface magnetic field that look a lot like gyres and flows in the oceans and the atmosphere, but these are being driven by fluid flow in the outer core,” Buffett said.

Buffett is a theoretician who uses observations to improve computer models of Earth’s internal dynamo. Now at work on a second-generation model, he admits that a lack of information about conditions in the Earth’s interior has been a big hindrance to making accurate models.

He realized, however, that the tug of the Moon on the tilt of Earth’s spin axis could provide information about the magnetic field inside. This tug would make the inner core precess — that is, make the spin axis slowly rotate in the opposite direction — which would produce magnetic changes in the outer core that damp the precession. Radio observations of distant quasars — extremely bright, active galaxies — provide precise measurements of the changes in Earth’s rotation axis needed to calculate this damping.

“The Moon is continually forcing the rotation axis of the core to precess, and we’re looking at the response of the fluid outer core to the precession of the inner core,” he said.

By calculating the effect of the Moon on the spinning inner core, Buffett discovered that the precession makes the slightly out-of-round inner core generate shear waves in the liquid outer core. These waves of molten iron and nickel move within a tight cone only 100 to 130 feet (30 to 40 meters) thick, interacting with the magnetic field to produce an electric current that heats the liquid. This serves to damp the precession of the rotation axis. The damping causes the precession to lag behind the Moon as it orbits Earth. A measurement of the lag allowed Buffett to calculate the magnitude of the damping, and the magnetic field inside the outer core.

Buffett noted that the calculated field — 25 Gauss — is an average over the entire outer core. The field is expected to vary with position.

“I still find it remarkable that we can look to distant quasars to get insights into the deep interior of our planet,” Buffett said.