A NASA satellite designed, built and controlled by the University of Colorado at Boulder is expected to help scientists resolve wide-ranging predictions about the coming solar cycle peak in 2012 and its influence on Earth’s warming climate, according to the chief scientist on the project.

Senior Research Associate Tom Woods of CU-Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics said the brightening of the Sun as it approaches its next solar cycle maximum will have regional climatic impacts on Earth. While some scientists predict the next solar cycle, expected to start in 2008, will be significantly weaker than the present one, others are forecasting an increase of up to 40 percent in the sun’s activity, said Woods.

Woods is the principal investigator on NASA’s $88 million Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE) mission, launched in 2003 to study how and why variations in the Sun affect Earth’s atmosphere and climate. In August, NASA extended the SORCE mission through 2012. The extension provides roughly $18 million to LASP, which controls SORCE from campus by uploading commands and downloading data 3 times daily to the Space Technology Building in the CU Research Park.

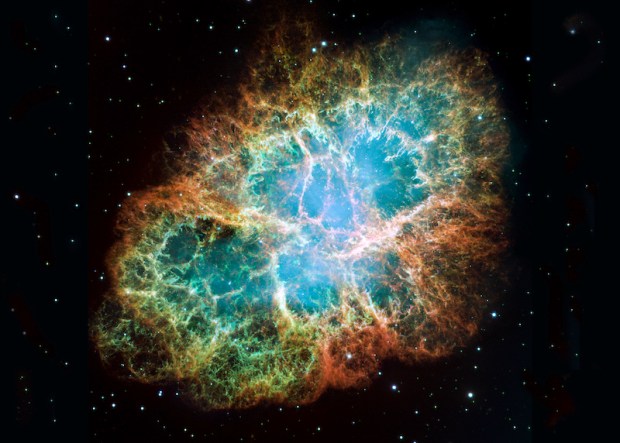

Solar cycles, which span an average of 11 years, are driven by the amount and size of sunspots present on the sun’s surface, which modulate brightness from the X-ray to infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. The current solar cycle peaked in 2002.

Solar activity alters interactions between Earth’s surface and its atmosphere, which drives global circulation patterns, said Woods. While warming on Earth from increased solar brightness is modest compared to the natural effects of volcanic eruptions, cyclical weather patterns like El Nino or human emissions of greenhouse gases, regional temperature changes can vary by a factor of eight.

During the most recent solar maximum, for example, the global mean temperature rise on Earth due to solar-brightness increases was only about 0.2° Fahrenheit, said Woods. But parts of the central United States warmed by 0.7° F, and a region off the coast of California even cooled slightly.

“It was very important to the climate change community that SORCE was extended, because it allows us to continue charting the solar irradiance record in a number of wavelengths without interruption,” Woods said. “Even relatively small changes in solar output can significantly affect Earth because of the amplifying affect in how the atmosphere responds to solar changes.”

With mounting concern over the alteration of Earth’s surface and atmosphere by humans, it is increasingly important to understand natural “forcings” on the Sun-Earth system that impact both climate and space weather, said Woods. Such natural forcing includes heat from the Sun’s radiation that causes saltwater and freshwater evaporation and drives Earth’s water cycle.

Increases in UV radiation from the Sun also heat up the stratosphere, located from 10 miles to 30 miles above Earth, that can cause significant changes in atmospheric circulation patterns over the planet, affecting Earth’s weather and climate, he said. “We will never fully understand the human impact on Earth and its atmosphere unless we first establish the natural effects of solar variability.”

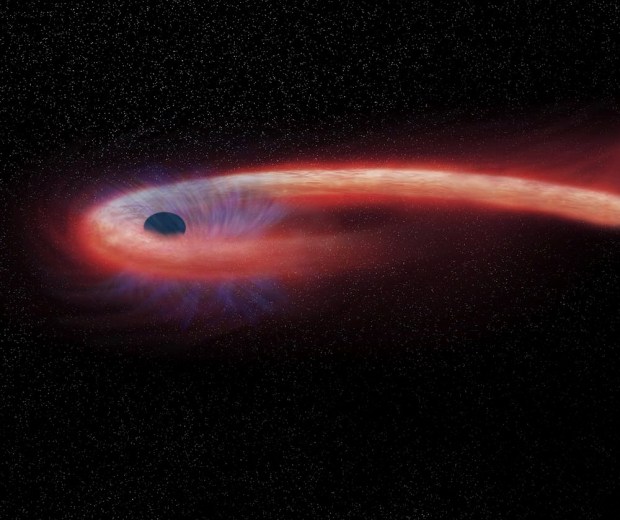

SORCE also is helping scientists better understand violent space weather episodes triggered by solar flares and coronal mass ejections that affect the upper atmosphere and are more prevalent in solar maximum and declining solar cycle phases, said Woods. The severe “Halloween Storms” in October and November 2003 disrupted GPS navigation and communications, causing extensive and costly rerouting of commercial “over-the-poles” jet flights to lower latitudes, he said.