Key Takeaways:

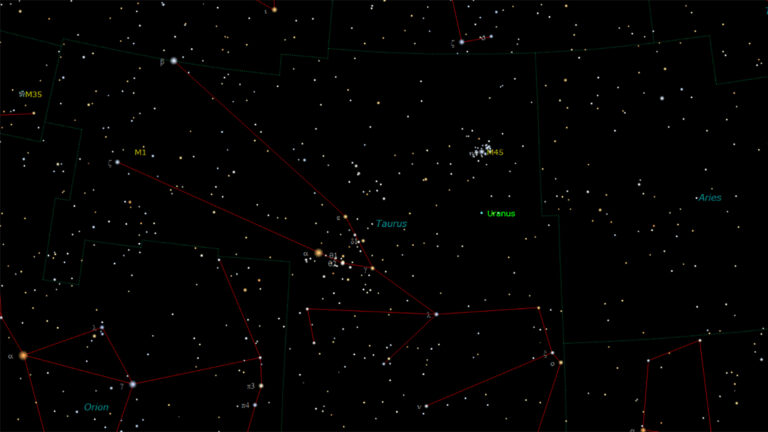

Venus had a crummy 2014, but it’s now returning with a vengeance. Look west 40 minutes after sunset for two “stars” near the horizon. The brighter is Venus, on the left. The other is Mercury. From the 8th to the 13th, they’ll hover strikingly close to each other.

They’re the only planets with no moons. The only ones that barely spin — needing months to rotate. (Every other planet’s day is less than 25 hours.) The only planets that can appear as crescents. The only ones with high densities similar to our world. These are intriguing resemblances.

But here’s what’s weird. In most other areas, they’re not merely dissimilar, but oddly opposite.

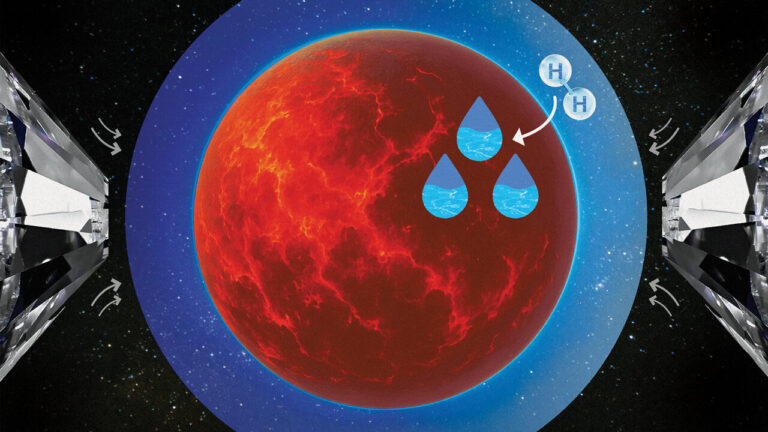

Venus’ surface sits under more air pressure than any other terrestrial body in the solar system. Its surface matches what you’d experience 3,000 feet (1,000 meters) below sea level — enough to crush a submarine’s hull. It’s like a defective pressure cooker about to explode. By contrast, Mercury is the only planet with virtually no air at all.

Venus is the shiniest planet by far. By contrast, Mercury is the least reflective. It’s as dark as an asphalt parking lot. Venus has the most circular path around the Sun of any planet. This gives it a steady cruise-control orbital velocity of 22 miles (35 kilometers) per second. It doesn’t vary. By contrast, Mercury has the most oval, squashed orbit, so it dramatically slows down and speeds up like a drunk driver. Someone on its surface would sometimes see the enormous Sun rise, then drop below the horizon, then rise a second time.

Next consider axial tilt. Venus’ is off the charts at 177°. That world is actually upside down. By contrast, Mercury has no tilt at all. Not even one degree. Not even half a degree. If you want to be picky, it’s 1/30°. The plane of its equator is its path around the Sun.

Mercury makes three spins while circling the Sun twice, the only planet with a resonance between its day and year. As a consequence, the period from one sunrise to the next is exactly two Mercury years. Nearly six months. Crazy slow. The Sun crosses as much of Mercury’s sky in a month as it traverses ours in two hours. During that long, grueling day, the Sun grows 1.5 times larger and more than doubles its intensity as the planet sizzles through its brutal perihelion. Then the Sun thankfully shrinks again.

SINCE IT REQUIRES 87 PERCENT OF LIGHT-SPEED TO MAKE TIME SLOW BY HALF ITS NORMAL RATE, WE’VE NEVER DIRECTLY EXPERIENCED TIME’S FICKLENESS.

Could the contrasts of those worlds get any odder?

Actually, yes. Venus has a nonexistent day/night temperature range. Its ultra-thick air keeps both its day and night hemispheres baking at an even thermostat setting of 870° F (465° C). You don’t need an oven there. The Cytherean gourmet cookbook calls for just two seconds for pot roast. Same for rice, since Venus’ high pressure only lets water boil above 500° F (250° C). But Mercury, always the contrarian, has the greatest day/night range of any object in the solar system. There, the mercury (ha!) plunges some 1,000° F (600° C) after sunset. Its rocks go from hot enough to melt lead to cold enough to liquefy oxygen.

The oddest observational contrast between these two worlds? Venus gets brightest when it’s on our side of the Sun and nearly at its closest to us. But Mercury is brightest when it’s about as far away as it can get.

Right now, both have recently emerged from behind the Sun, on the far side of their orbits. Thus, Mercury is now nearly at its brightest while Venus is dimmest. (Of course, even a “dim” Venus always outshines Mercury.) Venus alters its brightness threefold during its full synodic cycle. But Mercury varies its brilliance by an astonishing factor of 1,000, more than any other planet. This year its magnitude changes from –2.2 to 5.3, equaling the brightness difference between Vega and Neptune.

The second week of January finds Mercury in the bright section of its orbit at magnitude –0.8 and easy to spot close to Venus. Their conjunction, a bit low in the fading twilight, requires an unobstructed horizon.

They’re both fascinating and bizarre. Maybe the International Astronomical Union can change their designation so we don’t have to keep calling them inferior planets.

Contact me about my strange universe by visiting http://skymanbob.com.