Why are the jets emitted by black holes or neutron stars always concentrated like a laser?

Craig Case

Twain Harte, California

Astrophysical jets are rapid outflows from a central object that become focused into a narrow cone.

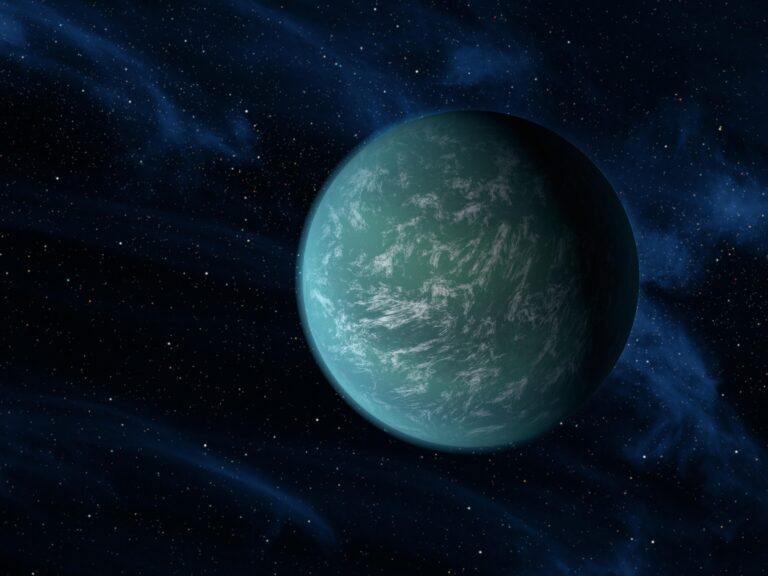

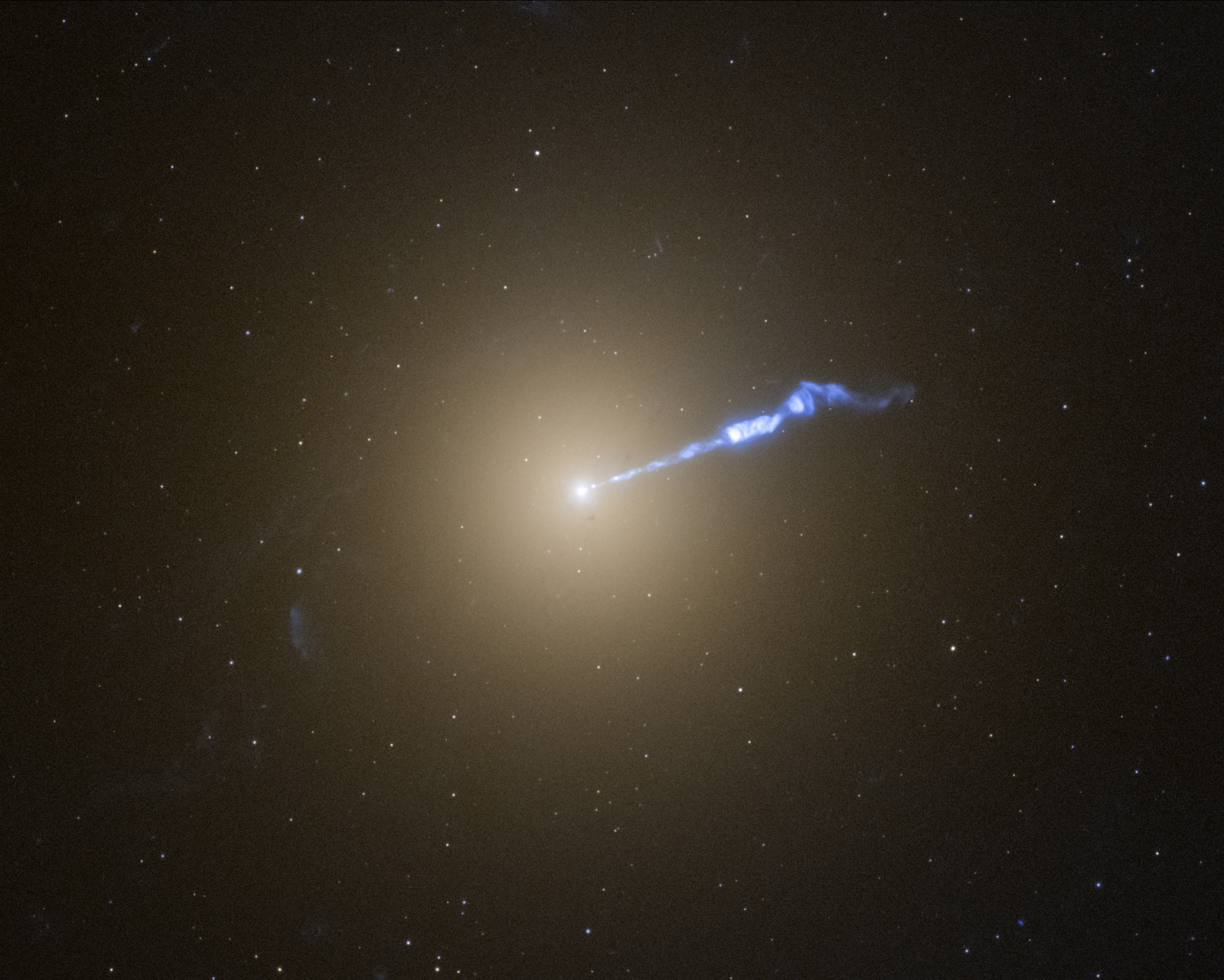

Jets are everywhere in astrophysics: They occur near supermassive black holes like the 6-billion-solar-mass monster at the center of the giant elliptical galaxy M87 in Virgo (see the image at lower left) as well as near stellar-mass black holes, such as the more-than-10-solar-mass black hole in GRS 1915+105 in Aquila. Jets are found at neutron stars in supernova remnants like the famous Crab Nebula (M1), whose blast was seen in the year 1054, and also near neutron stars that draw mass from nearby companions, like Circinus X-1. Jets are also observed in gamma-ray bursts that originate from black holes and neutron stars. And they are seen near sub-solar-mass young stars such as the famous object Herbig-Haro 30 (see the image at upper left), which, as captured by the James Webb Space Telescope, looks like a beam from the Death Star.

These objects differ in size, temperature, luminosity, and nearly every other respect. But all contain jets.

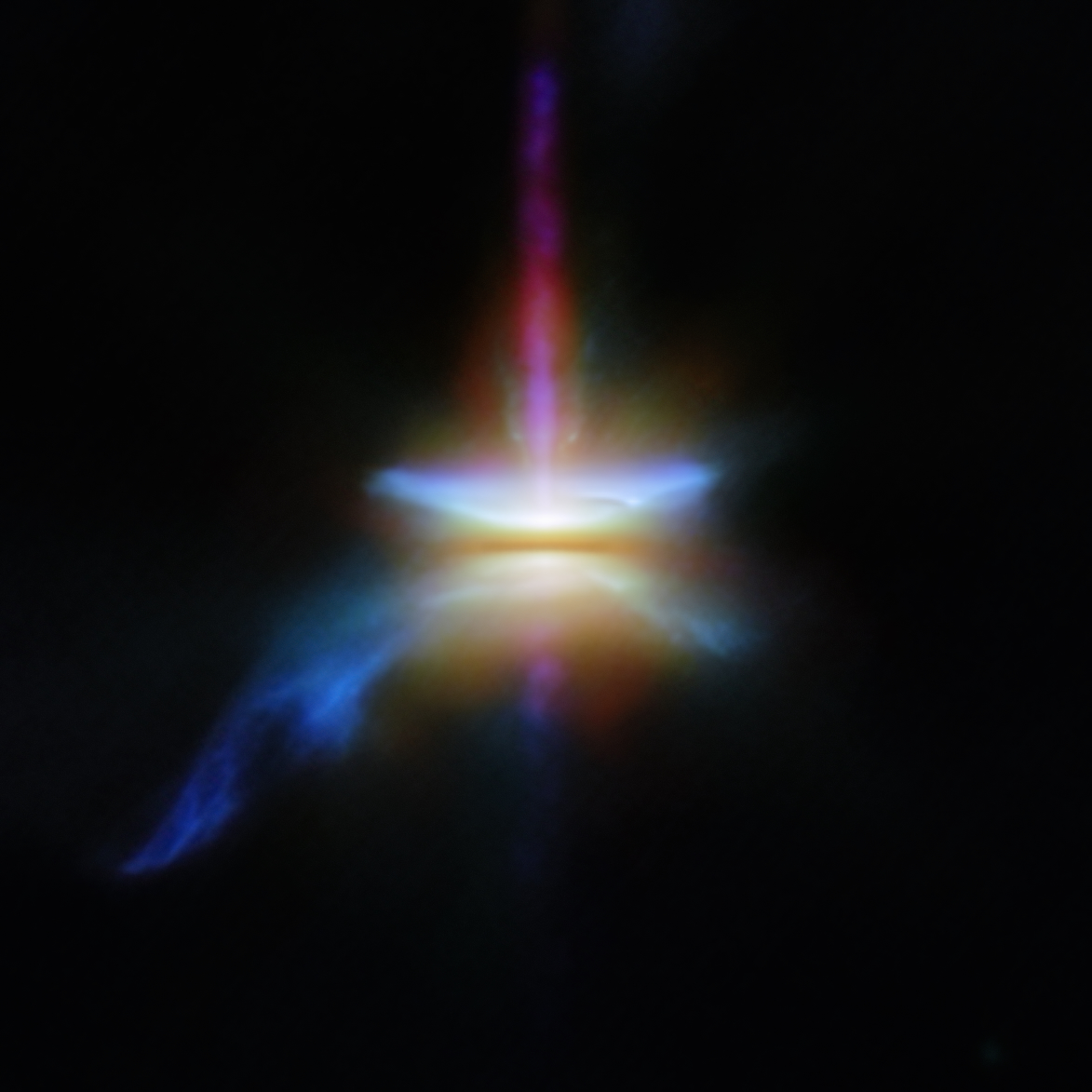

The origin of jets is not yet fully understood. It is the subject of controversy, theoretical attention, and the target of countless hours of research telescope time. At least two ingredients, however, are probably needed to make jets: rotation and magnetic fields.

First, the central object (black hole, neutron star, ordinary star, etc.) must rotate, acting as a flywheel from which energy can be drawn to power the jet. That central object is invariably embedded in hot, ionized gas, in which the atoms have been stripped of some of their electrons. This makes the gas highly electrically conductive. Because the gas is conductive, it can interact with magnetic fields. The fields are caught by the central object (even if it is a black hole!) like ribbon caught on a rotating spindle.

The magnetic field connects the central object to the surrounding gas, pushing on the gas and causing it to rotate until is far from the central object. The field also draws gas inward toward the axis of rotation, focusing the outflow into a jet.

This is just part of the story, because jet sources are so different. But rotation and magnetic fields, which are also everywhere in astrophysics, seem to have a part in all of them, and produce the ubiquitous laserlike jets we see.

Charles F. Gammie

Ikenberry Chair in Astronomy and in Physics, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign