Key Takeaways:

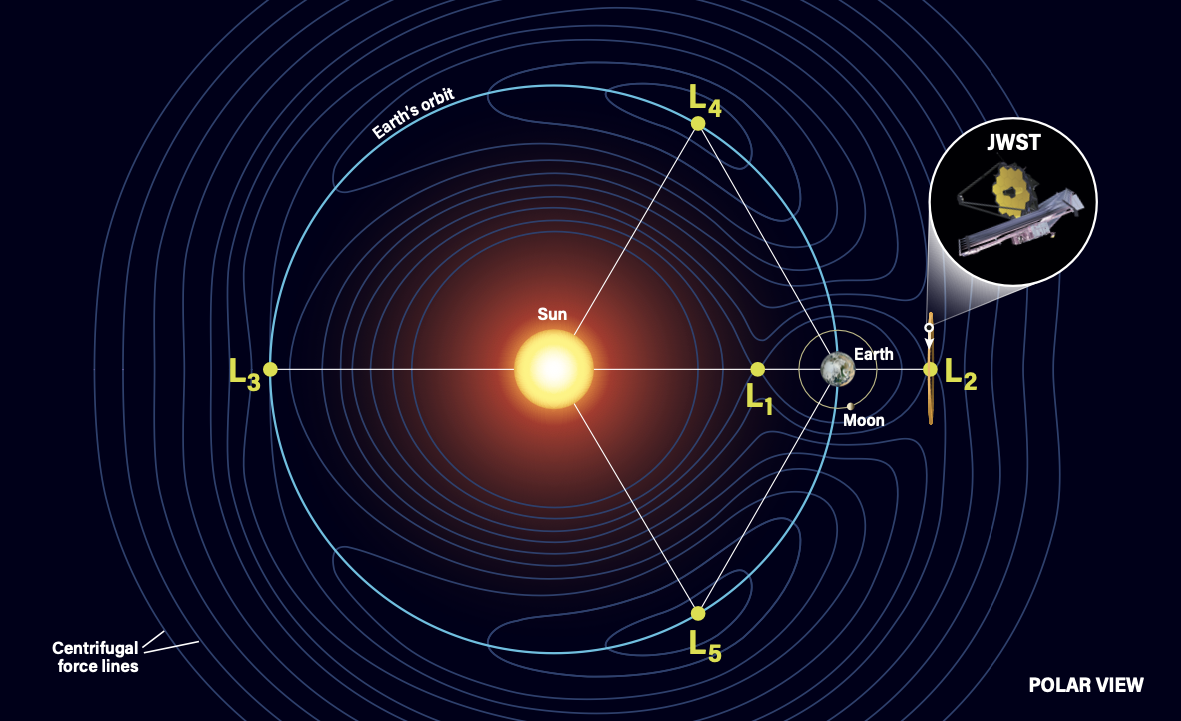

- Lagrangian points (L points) are five specific regions within a two-body orbital system where gravitational forces achieve a state of balance, theoretically allowing a third body to maintain its position with minimal energy expenditure.

- Three points, L1, L2, and L3, are aligned with the two primary bodies: L1 is situated between them, L2 on the far side of the orbiter relative to the parent, and L3 on the far side of the parent relative to the orbiter. The remaining two, L4 and L5, are located 60° ahead of and behind the orbiting body, forming equilateral triangles with the primary masses.

- Initially theoretical, L points were mathematically described by Joseph-Louis Lagrange in 1772 and later observationally confirmed starting in 1906 with the discovery of asteroids, known as Trojans, at Jupiter's L4 and L5 points.

- L4 and L5 points are long-term stable, provided the mass ratio of the primary bodies exceeds 24.96, whereas L1, L2, and L3 are less stable and require periodic orbital corrections for spacecraft deployed there, such as the Solar Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) at L1 and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) at L2.

What are Lagrangian points?

Dean Treadway

Jesup, Georgia

The Lagrangian equilibrium stability points, or L points, are the five places where the combined gravitational forces of two bodies produce regions of gravitational balance. These are little pockets where other bodies can, in theory, remain orbiting in place without expending much energy.

Three of these L points, L1, L2 and L3, are along the line connecting the orbiting body and its parent body: L1 is located between them, at a point closer to the orbiter. L2 is on the far side of the orbiter relative to the parent, and L3 is on the far side of the parent relative to the orbiter.

The other two, L4 and L5, move along the path of the orbiting body, 60° ahead of and 60° behind the orbiter. The L4 and L5 points could each mark the apex of an equilateral triangle, with the parent and orbiter marking the other two points.

In his 1772 paper “Essai sur le Problème des Trois Corps” (“Essay on the Three-Body Problem”), Italian-French mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange mathematically determined that such stable points could exist within an orbiting system. At the time, these points were merely theoretical constructs.

In 1906, however, astronomer Max Wolf at the Königstuhl Observatory in Heidelberg, Germany, discovered the asteroid 588 Achilles at the L4 point in Jupiter’s orbit. Within the next year, two other asteroids were found at Sun-Jupiter L points: The asteroid 624 Hektor was observed at L4, and 617 Patroclus was discovered at Jupiter’s L5. Soon thereafter, the prolific asteroid-discoverer Johann Palisa suggested that asteroids at Jupiter’s L4 and L5 points be named for heroes from the Trojan War — the asteroids at L4 for Greek figures and those at L5 for Trojans. (Despite this convention’s adoption, this is not true of the names for all 4,601 asteroids now known to exist at L4, nor the 2,439 at L5. Additionally, by this convention, Hektor and Patroclus are in the wrong “camps,” and so are sometimes referred to as “spies.”)

Today, all bodies located at the L4 or L5 points of any orbiting body are known as Trojans. Astronomers have so far only found two Earth-Sun Trojans, 2010 TK7 and 2020 XL5, both of which are located at L4.

Note that the L1, L2, and L3 points are not stable over the long term. L4 and L5 are stable provided that the mass ratio between the parent and orbiting bodies exceeds 24.96, a mass ratio that certainly holds for every planet-Sun pair in our solar system. Although the other points are less stable, spacecraft have been deployed to them. For instance, the Solar Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) satellite is currently in a halo orbit around Earth’s L1 point, located 932,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth, in the direction of the Sun. And, of course, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and the European Space Agency’s Gaia probe are currently in orbit around L2, also 932,000 miles (1.5 million km) from Earth, but on the far side of Earth relative to the Sun. As L1 and L2 are stable only over the short term — up to about 23 days — these spacecraft have to undergo periodic course and altitude corrections. All the same, these L points are prime locations for spacecraft, as they don’t need to expend great quantities of fuel to maintain their positions there.

No space agency has bothered to send any craft to L3 and there are no natural bodies around that point. The popular science-fiction convention that a secret planet lurks there seems highly unlikely because L3 is unstable, so an object as massive as a planet would not be able to remain there for long.

Edward Herrick-Gleason

Astronomy Educator, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador