Credit: NIR Keck image

Astronomers recently watched a massive star die, but fail to explode as a supernova. Instead, it collapsed directly into a black hole, slowly expelling its turbulent outer layers in the process. This observation of a star’s transformation into a black hole has produced a new theory explaining how this happens.

The results, published February 12 in Science, will help explain why some massive stars turn into black holes when they die, while others don’t.

“This is just the beginning of the story,” says Kishalay De, an associate research scientist at the Simons Foundation’s Flatiron Institute and lead author on the new study. Light from dusty debris surrounding the newborn black hole, he says, “is going to be visible for decades at the sensitivity level of telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope, because it’s going to continue to fade very slowly. And this may end up being a benchmark for understanding how stellar black holes form in the universe.”

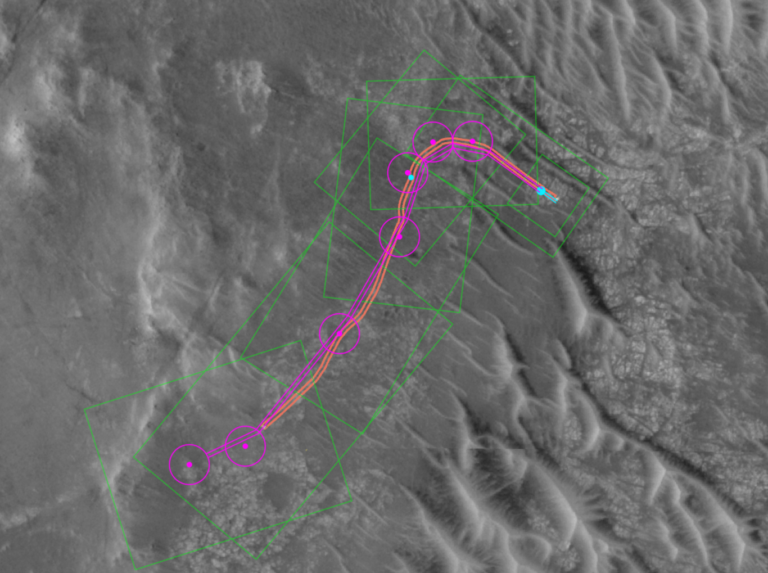

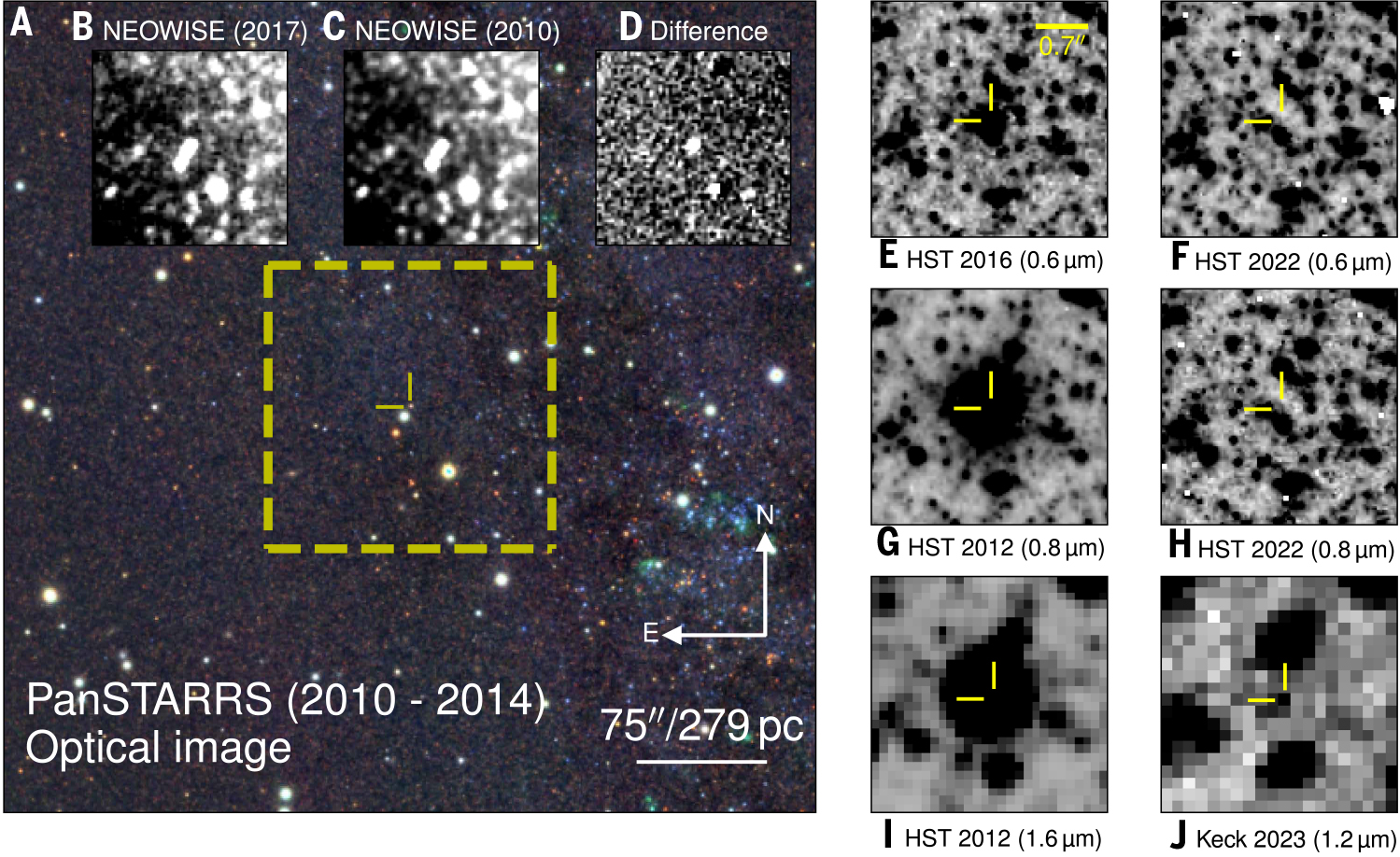

The star, designated M31-2014-DS1, is located 2.5 million light-years away from Earth in the neighboring Andromeda Galaxy (M31). De and his collaborators analyzed measurements from NASA’s NEOWISE project and other ground- and space-based telescopes from 2005 to 2023. They found that M31-2014-DS1’s infrared light began brightening in 2014. Then in 2016, the star had a large drop in brightness.

Observations in 2022 and 2023 showed that the star’s output of visible and near-infrared light dropped to one ten-thousandth of what it was before. Currently, the star is only detectable in mid-infrared light, and that’s only one-tenth as bright as before.

De says, “This star used to be one of the most luminous stars in the Andromeda Galaxy, and now it was nowhere to be seen. Imagine if the star Betelgeuse suddenly disappeared. Everybody would lose their minds! The same kind of thing [was] happening with this star in the Andromeda Galaxy.”

What should happen

Comparing their observations with theories, the researchers concluded that the star’s dramatic fading showed that its core collapsed and became a black hole.

Hydrogen transforms into helium in the cores of stars through a process called nuclear fusion, which generates all of their energy. For most of their lives, the outward push of that energy balances the inward pull of gravity, and the star is in balance. But when a star 10 or more times as massive as our Sun begins to run out of fuel, the balance is disrupted. Gravity begins to collapse the star, and its core succumbs first to form a dense neutron star at the center.

At this point, there’s a huge outrush of neutrinos that generates a powerful shock wave. Usually, this creates a powerfulexplosion called a supernova, which blasts much of the star’s material into space. But if the neutrino-powered shock wave fails to cause an explosion, theory says that most of the star’s material would fall back into the neutron star, forming a black hole.

“We’ve known for almost 50 years now that black holes exist,” says De, “yet we are barely scratching the surface of understanding which stars turn into black holes and how they do it.”

What is happening

While they were studying M31-2014-DS1, the team realized that no previous theory took into account a process going on in the star’s outer layers. What other scientists had failed to take into account was convection.

Convection results from the vast temperature differences inside the star. Material near the star’s center is extremely hot, while the outer regions, in comparison, are much cooler. This difference causes gas inside the star to move from hotter to cooler regions.

When the star’s core collapses, the gas in its outer layers is still moving rapidly due to this convection. Theoretical models developed by the researchers show that this prevents most of the material from falling into the core. Instead, the innermost layers orbit near the black hole and drive the ejection of the outermost layers of the convective region. And it’s a slower process than would happen if the star exploded.

Co-author and Flatiron Research Fellow Andrea Antoni previously developed the theoretical predictions for these convection models. With the data from M31-2014-DS1, she says, “the accretion rate — the rate of material falling in — is much slower than if the star imploded directly in. This convective material has angular momentum, so it circularizes around the black hole. Instead of taking months or a year to fall in, it’s taking decades. And because of all this, it becomes a brighter source than it would be otherwise, and we observe a long delay in the dimming of the original star.”

Only about one percent of the star’s original atmosphere falls into the black hole, powering the light that emanates from it today, the researchers estimate.

This star isn’t alone

While analyzing M31-2014-DS1, De and his team also reevaluated a similar star, NGC 6946-BH1, which was studied10 years ago. In their paper, they explain why this star followed a similar pattern. M31-2014-DS1 initially stood out as an “oddball,” De says, yet it now appears to be just one member in a class of objects — including NGC 6946-BH1.

“It’s only with these individual jewels of discovery that we start putting together a picture like this,” De says.