Key Takeaways:

- The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), employing its infrared capabilities, offered new insights into the Sombrero Galaxy (M104), revealing previously hidden stars by softening the appearance of its prominent dust lane.

- M104 is distinguished as the most luminous galaxy within 35 million light-years, encompassing approximately 800 billion solar masses, a 9-billion-solar-mass central supermassive black hole, and an extensive collection of around 2,000 globular clusters.

- The galaxy presents a classification enigma due to its hybrid morphology, combining a spiral-like dust disk with a massive, elliptical-like central bulge and halo, without the typical chaotic indicators of a recent merger.

- JWST observations, including data from its Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) showing a warped inner disk and clumpy outer dust ring suggestive of active star formation, combined with the diverse compositions of its globular clusters, support the hypothesis of a long-past merger event.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has a habit of showing familiar objects in a new light. With cameras sensitive to a broad range of infrared wavelengths, it can peer deep into celestial objects, revealing details often hidden to telescopes that view visible light.

The aptly named Sombrero Galaxy (M104) provides a stunning example. At optical wavelengths, the galaxy features a thick dust lane that cuts across a spherical bulge of bright stars. Early skygazers noted the resemblance to a traditional Mexican hat with its broad brim and high crown, and the object’s proper name was born.

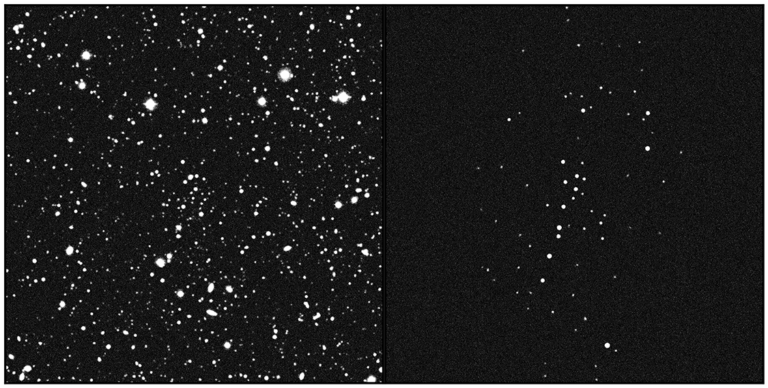

When JWST’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) captured M104 in June (far right), it softened the dust lane’s appearance and exposed previously hidden stars. The old stars in the galaxy’s bulge produce significant amounts of near-infrared radiation, which passes through all but the thickest dust clouds relatively unscathed.

A superlative galaxy

The Sombrero lies some 30 million light-years from Earth on the outskirts of the Virgo galaxy cluster. It reigns as the most luminous galaxy within 35 million light-years of Earth. To earthbound observers, this means it glows bright enough (8th magnitude) to spot through binoculars from a dark site.

Most of this luminosity comes from an abundance of stars. The Sombrero packs roughly 800 billion solar masses of material into a volume slightly less than that of the Milky Way Galaxy. M104 also harbors a central supermassive black hole that weighs about 9 billion solar masses. Yet this behemoth just nibbles on its surroundings and shows only weak signs of activity.

The Sombrero also dwarfs the Milky Way in its collection of globular clusters. Some 2,000 of these ancient star cities orbit M104, while the Milky Way harbors less than 200. All seem to have formed in the galaxy’s early days, some 10 billion to 13 billion years ago.

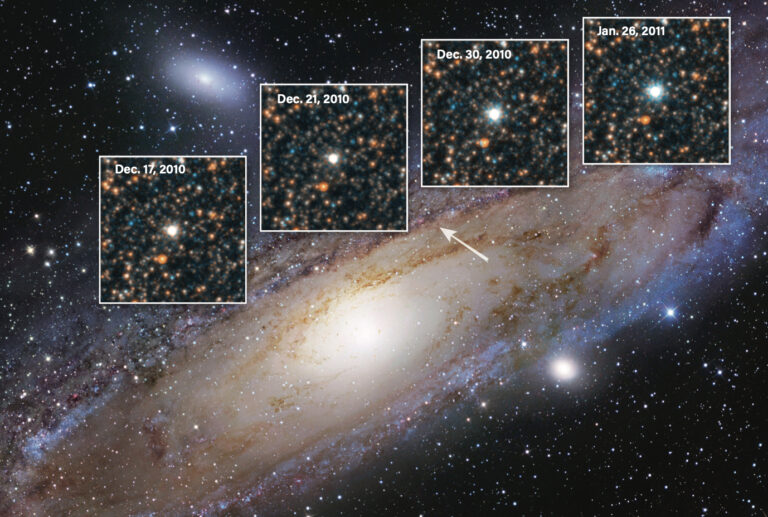

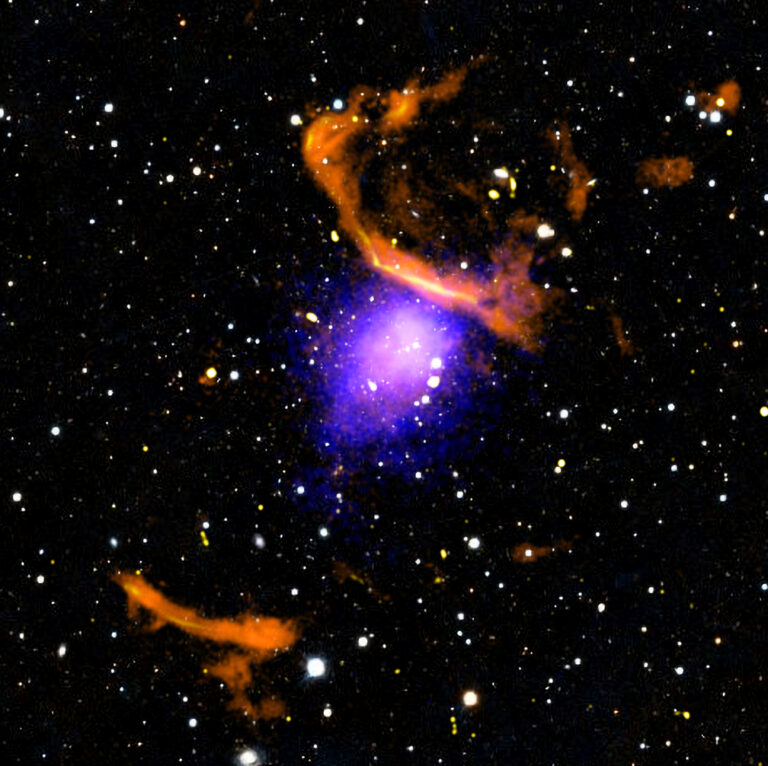

Astronomers still don’t know how to classify the Sombrero. The galaxy’s dust-laden disk resembles that of a normal spiral galaxy, but the massive central bulge and halo look like those of a typical giant elliptical galaxy. No one thinks the Sombrero could be the result of a recent merger. Such unions typically produce a chaotic appearance like that seen in the Antennae Galaxies (NGC 4038/9).

A long-ago merger

The JWST observations support the idea that the Sombrero’s hybrid look comes from a collision and ultimate merger with at least one other galaxy several billion years ago. Fortunately for scientists, the galaxy tilts 6° to our line of sight. The slight angle allows JWST a clear view into the Sombrero’s interior.

In late 2024, researchers targeted the Sombrero with the observatory’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). Because MIRI observes at longer wavelengths than NIRCam, it captures a different picture. Most stars emit little mid-infrared radiation, so they disappear from view. But their light heats interstellar dust and causes it to glow at these wavelengths.

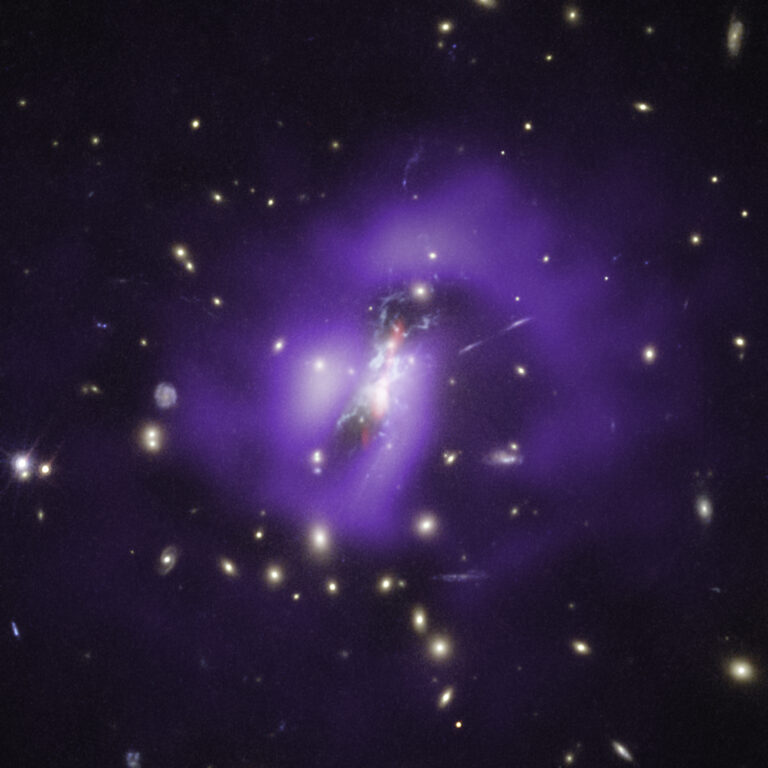

The MIRI image (opposite page) reveals a broad outer dust ring surrounding an inner disk centered on the galaxy’s brilliant core. The inner disk appears slightly warped, a signature of an ancient interaction with another galaxy. Also note the dust clumps in the outer ring, which JWST revealed for the first time. These are likely areas where stars are currently forming.

The globular clusters offer another intriguing hint to the Sombrero’s violent past. Such clusters usually have similar compositions, but the ones in M104 show a surprising diversity. Astronomers suspect that they formed in different galaxies that merged with the Sombrero billions of years ago.