If you were to ask a group of dedicated amateur astronomers to list their favorite telescopic targets, few if any would mention asteroids. That’s easy to understand. The typical asteroid lacks the jaw-dropping visual impact of the Moon or Saturn. Through the eyepiece, an asteroid is an ordinary-looking stellar speck. In fact, the word asteroid comes from the Greek word asteroeides, which means “starlike.”

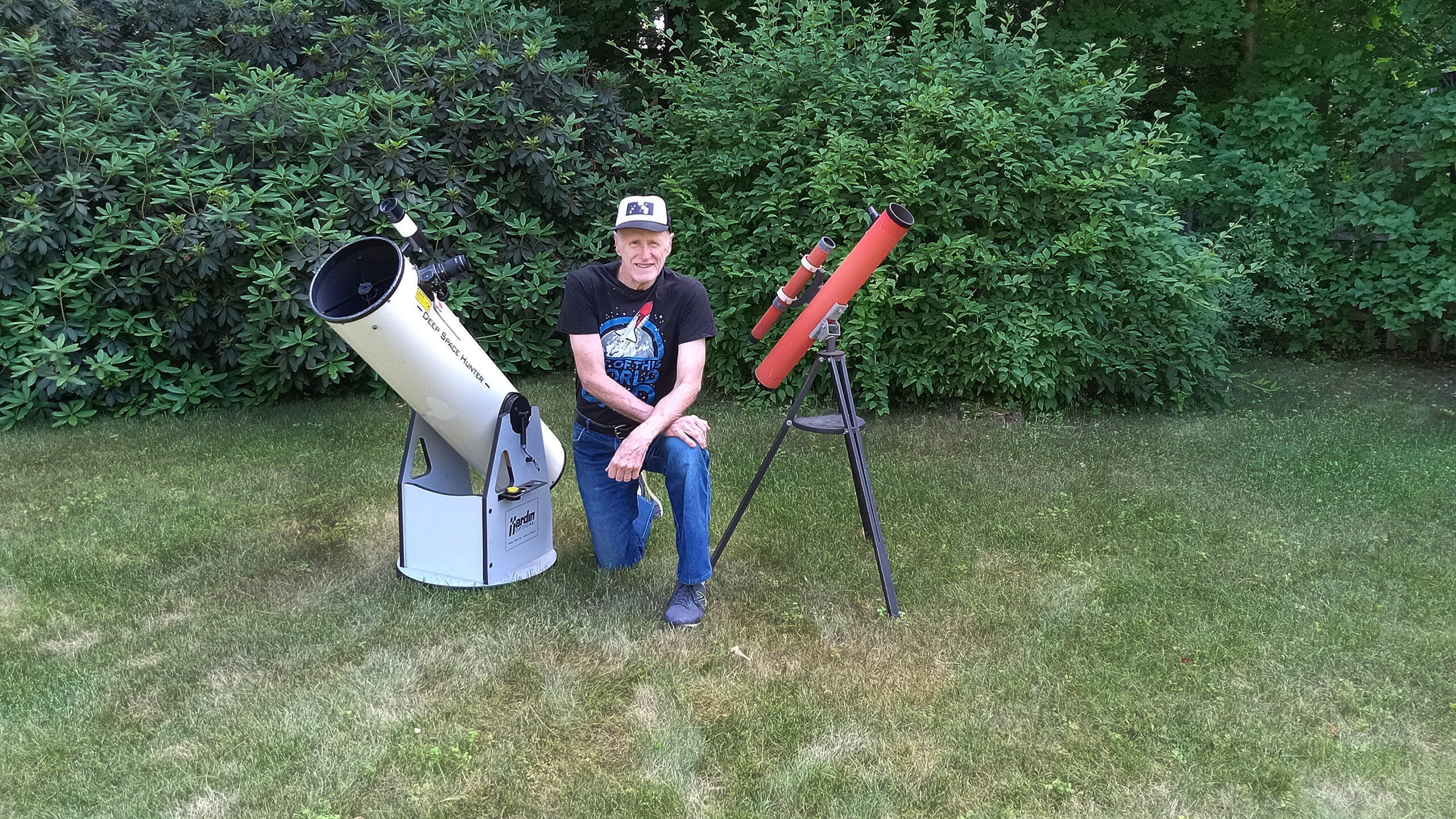

My interest in observing asteroids began in the summer of 1971 when I came across information in an astronomy magazine about the then-visible asteroid 4 Vesta. Using the accompanying finder chart, I spotted Vesta with a handheld 6x refractor. A few months later, another featured asteroid led me to 8 Flora, which I spotted using a 3-inch f/10 reflecting telescope (Edmund Scientific’s classic Space Conqueror). That observation evolved into a lifelong quest to notch as many asteroids as possible with that scope. To date, the Space Conqueror has lived up to its name by finding more than 120, including the first 33 discovered and 64 of the first 100.

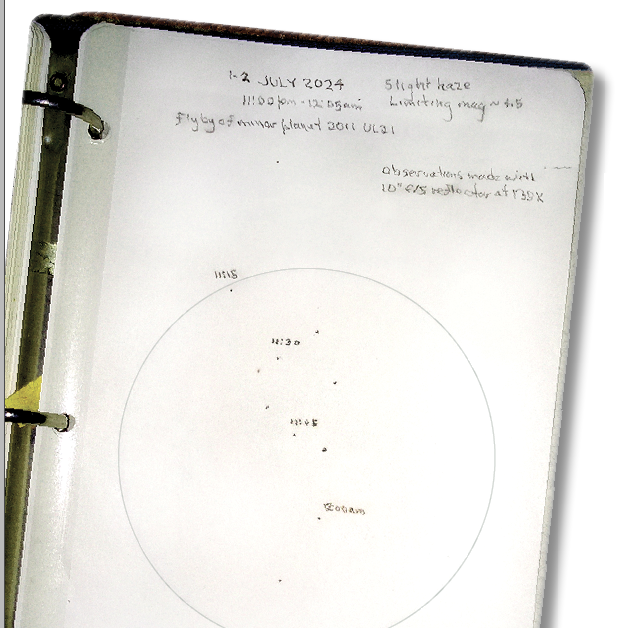

More recently, I’ve upped my game a notch by adding near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) to the mix. Because they’re small, usually less than a few hundred yards in diameter and therefore relatively faint, I chase them with a 10-inch f/5 reflector.

Despite their visual shortcomings, asteroids rank near the top of my favorite celestial objects. Stay with me, and I’ll explain why you should add them to your observing repertoire, whether you’re a novice or a seasoned observer.

Asteroids 101

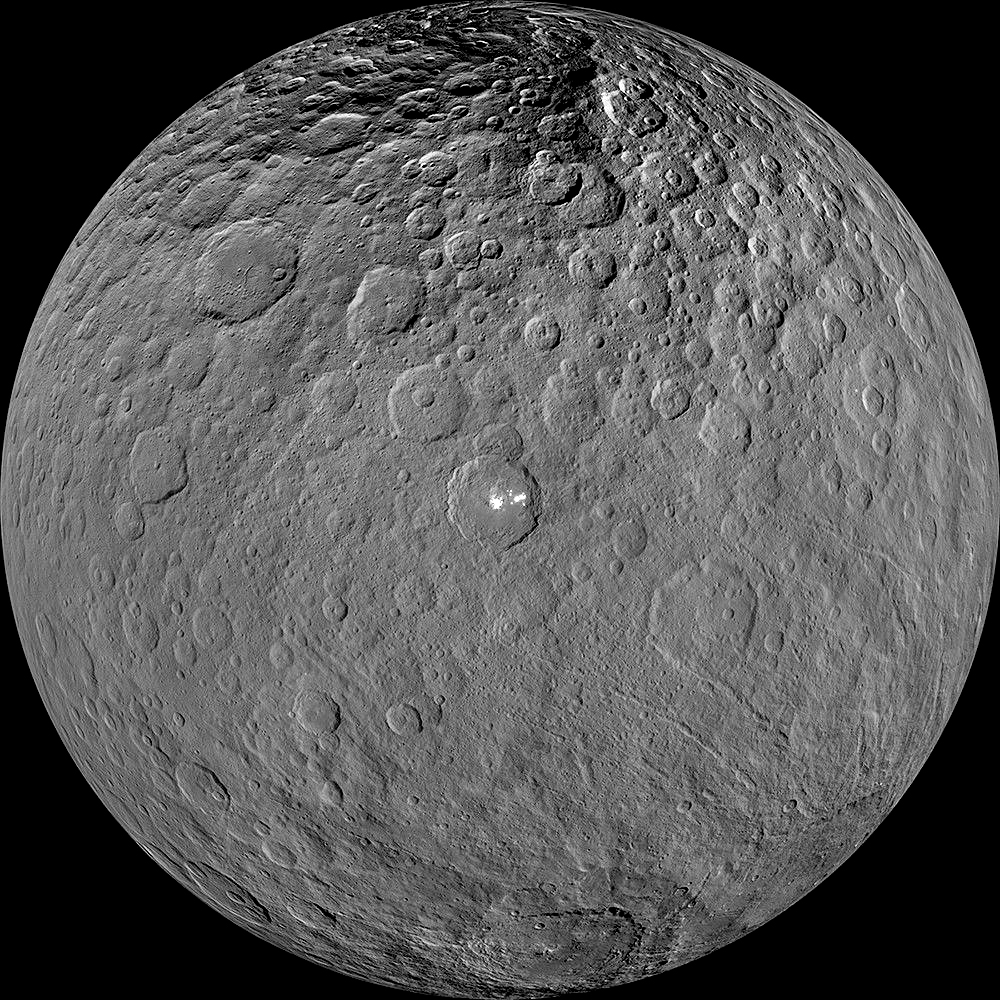

First, let’s get up to speed on these objects. Webster’s Dictionary defines an asteroid as a small, rocky celestial body that orbits the Sun, particularly between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. The terms asteroid and minor planet are often interchanged. However, minor planets exist throughout the solar system. Asteroids are those minor planets that inhabit the inner solar system and have a rockier composition than their icy outer solar system cousins, the largest of which are called dwarf planets.

Asteroids that orbit the Sun between Mars and Jupiter are known as main-belt asteroids. These are the remnants of a planet that failed to form between the two, thanks to Jupiter’s gravitational influence. Millions inhabit this so-called asteroid belt, ranging in size from Vesta, whose diameter is 326 miles (525 kilometers), to bodies less than 3 feet (1 meter) across. Throw in bodies with diameters less than 3 feet, technically defined as meteoroids, and the population might number in the trillions. Despite these numbers, the asteroid belt is relatively barren — not the jumble of space rocks the Millennium Falcon had to dodge in The Empire Strikes Back.

If you’ve watched doomsday movies about asteroids striking Earth, you know that not all are safely ensconced in the asteroid belt. Asteroids are found throughout the inner solar system, and a frighteningly large subset of them, the NEAs, have orbits that approach and even intersect Earth’s. NEAs are believed to have been pushed sunward out of the asteroid belt either through gravitational interactions with Jupiter or through collisions with other asteroids. As of mid-2025, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) says that more than 38,800 NEAs had been discovered. By year’s end, that number may well exceed 40,000. Two-thirds of these actually cross Earth’s orbit, and of these more than 2,300 get close enough (within 20 lunar distances) and are large enough (300 feet [91 m] or more) to be considered potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs).

The formal identification for an asteroid is a number in parentheses followed by its name, for example, (4179) Toutatis. The parentheses are often omitted — and even the number may be dropped if the asteroid is mentioned more than once in an article. Originally, the number indicated the asteroid’s order of discovery, but as more and more asteroids were discovered and then lost, they were given a provisional designation which included the four-digit year of discovery, followed by a letter indicating the half-month of discovery and a second letter indicating the order within that half-month. (There’s even an added subscript number if a huge amount of asteroids are discovered during a half-month period, but that’s more of an Asteroids 102 topic.) Toutatis’ provisional designation was 1989 AC, meaning it was the 3rd asteroid discovered between January 1 and 15, 1989. Only after Toutatis’ orbit was well-determined did it get its official number and name.

Get started

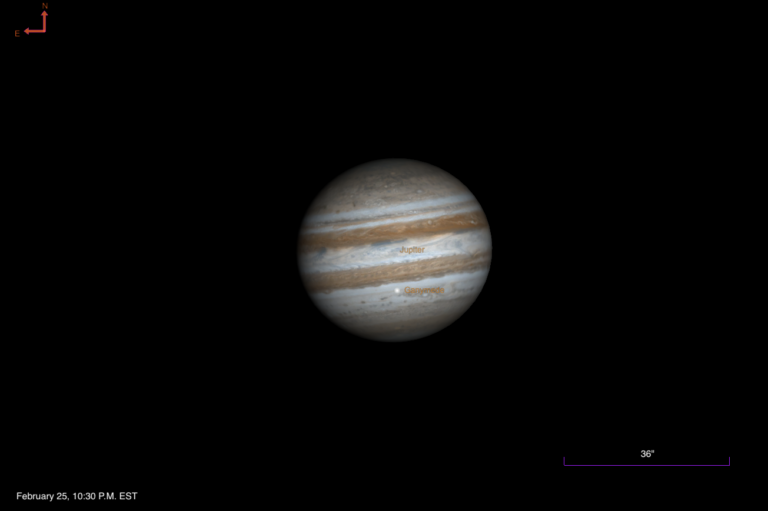

You can begin your asteroid-seeking odyssey the same way I did, with a bright main-belt asteroid. As my 3-inch reflector proved to me, an expensive, large-aperture telescope isn’t necessary. Dozens of asteroids reach magnitude 10.5 or brighter during their oppositions, well within reach of a 2.4-inch refractor. In fact, bright ones like Vesta are within reach of binoculars. For info on the bright, currently-visible asteroid 1 Ceres, turn to page 35. There, you’ll find information about Psyche, including a map to help you find it.

With map in hand, go outside and aim your telescope toward Ceres’s predicted position. If you see a starlike object there, congratulations! You’ve spotted your first asteroid. The sight may not have given you an adrenaline rush, but you have to admit it’s a pretty satisfying achievement. If you’re like me and want to make sure you’ve found the “real deal,” you may want to observe the asteroid on subsequent evenings. If the starlike speck you saw is no longer there and it now appears in an area of sky that was previously blank, you can be 100 percent sure you’ve made the observation.

If viewing your first asteroid gives you a thirst for more, you can try again next month with the featured asteroid in the next issue of Astronomy. Can’t wait? There are several websites that provide information and finder charts on currently visible asteroids. Try astro.vanbuitenen.nl/asteroids, sky-tonight.com/asteroids, or in-the-sky.org/data/asteroids.php.

By and large, the asteroids we’re talking about so far are main-belters. At their opposition distance, anywhere between 112 million and 205 million miles (180 million and 330 million km), their apparent motion is rather small, perhaps ½° (one Moon diameter) in 24 hours. This makes them relatively easy pickings for the novice. The typical NEA, on the other hand, can cover that distance in a single hour or less. These moving targets require a little more experience.

If you’re up to chasing down one of the NEAs, start with the spaceweather.com website. Scrolling down, you’ll find a section labeled “Near Earth Asteroids,” which includes a list of recent and upcoming NEA encounters spanning roughly two months. Despite its closeness, the typical NEA is rather small and faint, best seen with medium- to large-aperture instruments. To find the most reachable NEAs, focus in on two columns: the miss distance, expressed in lunar distances (LDs), and the diameter in meters. Ideally, you’ll want an NEA whose miss distance is less than 5 LDs and whose diameter exceeds 300 meters — in other words, one that will be bright enough (14th magnitude or better) to pick out with an 11-inch or larger scope. Be sure to jot down the date of closest approach.

The next step is to find out where in the sky and how bright your target NEA will be. A go-to source for this information is the IAU’s Minor Planet and Comet Ephemeris Service (https://minorplanetcenter.net/iau/MPEph/MPEph.html). In the appropriate spaces, type in the asteroid’s identity (for most NEAs, the discovery nomenclature), an ephemeris start date (I suggest one day before close approach), and request its hourly coordinates over a 48-hour period. Using these coordinates, trace the asteroid’s path on a star atlas, looking for instances when it passes a bright star or distinguishable asterism. Finally, I tailor-make and print out a chart using the American Association of Variable Stars Variable Star Plotter (https://apps.aavso.org/vsp — check it out, it’s a neat and free tool) on which I plot the asteroid’s locations from an hour before until an hour after its encounter with the star or asterism. It’s important that my chart include stars up to a magnitude fainter than the asteroid.

What to expect

To describe what happens next, let me put you at the eyepiece as the NEA makes its appearance. You’re gazing at the asterism you chose as an ambush site. It’s still a few minutes away from the time of the asteroid’s predicted passage. You see nothing yet. The minutes pass. Still nothing! Could the predictions have been off? Then you spot it at the edge of the eyepiece field — a stellar speck moving slowly towards the asterism. You realize that this innocent-looking speck is in reality an asteroid the size of a battleship passing 4 LDs (about a million miles) from Earth at a speed of several miles per second.

Were it to drift directly across the Earth’s orbital path at that distance, it would miss us by a matter of hours. An impact on land would create a crater more than 2 miles (3.2 km) across and cause millions of casualties if it struck a populated area. A hit in the ocean would generate tsunamis hundreds of feet high, creating an even greater loss of life in coastal communities. Regardless of where it hit, the asteroid would affect weather patterns on a global scale. Eye glued to the eyepiece, you take a deep breath. Then it passes, and all is well.

Whenever it has been announced that a near-Earth asteroid will make a close pass, I check to see if it’s included in the database of the planetarium software I use, Sky Safari Pro. If it is, I center the object, then let time pass, watching for easy-to-find and easy-to-identify asterisms along its path. Then, I locate the asterism in my eyepiece and wait for the asteroid to come to me. I have found this to be a successful method for spotting these faint space rocks. Good luck!