Key Takeaways:

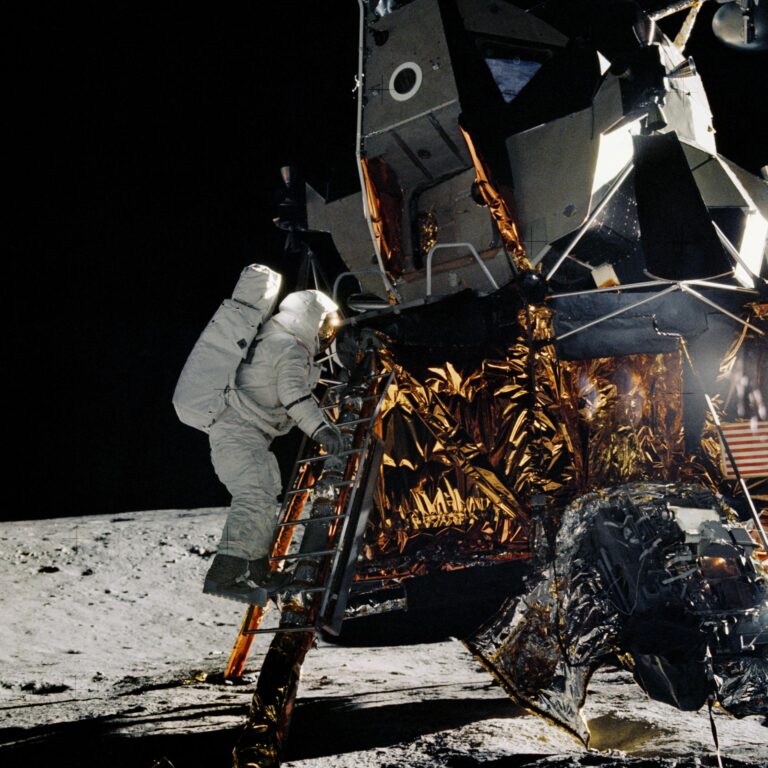

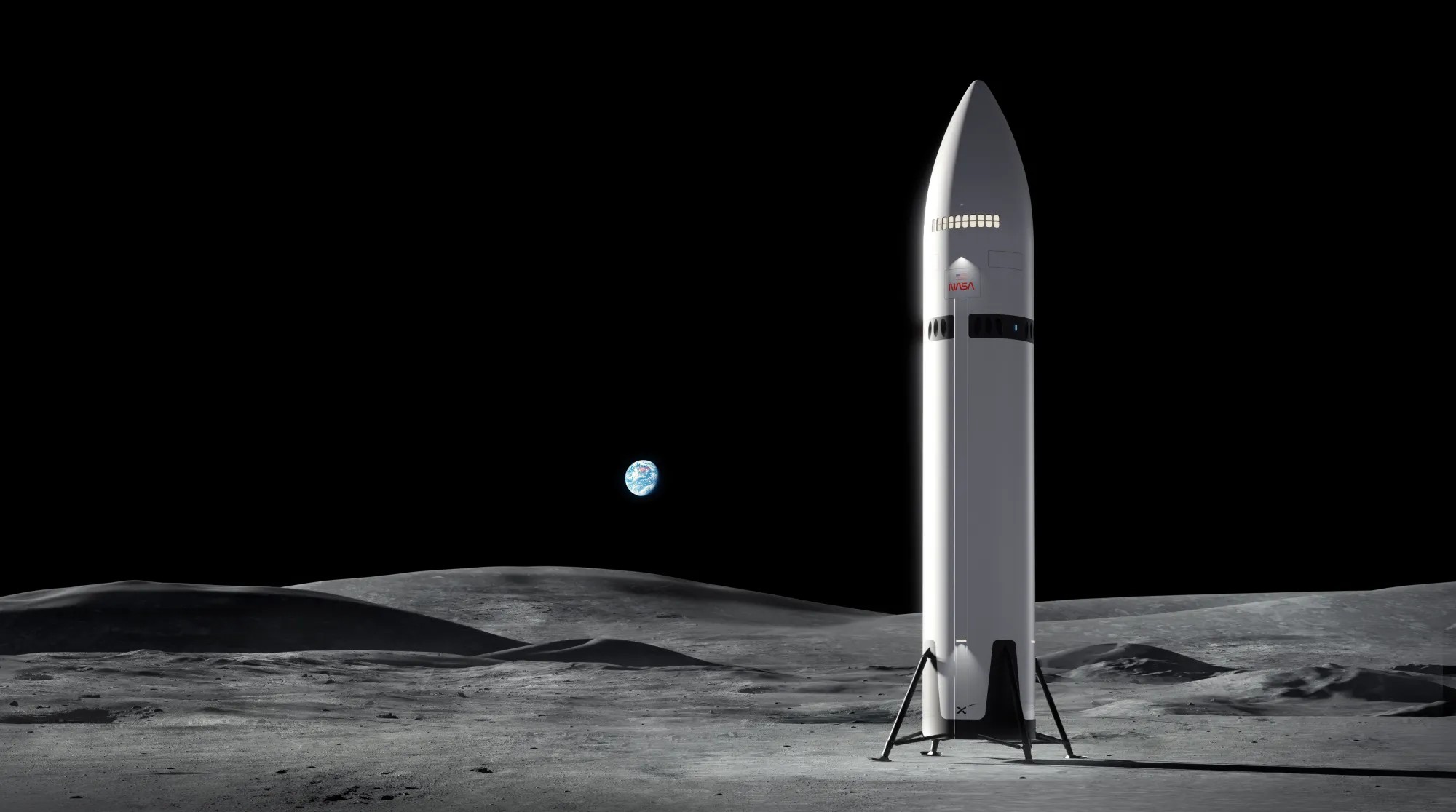

- NASA's Artemis 3 mission, aiming for the first crewed lunar landing since the Apollo era, currently lacks a definitive Human Landing System (HLS) architecture and faces an uncertain launch timeline, despite an official mid-2027 forecast.

- SpaceX, initially contracted for Artemis 3 and 4 HLS and having received $2.7 billion, has been publicly identified by NASA as "behind" on development, with critical milestones such as orbital propellant transfer and human-rating of its Starship HLS still pending, the former targeted for 2026.

- Blue Origin, which holds an HLS contract for Artemis V and has received $835 million, is exploring an uncrewed lunar landing for its Blue Moon Mk1 variant as early as this year, although its New Glenn rocket has undergone only one test flight.

- Both proposed HLS architectures necessitate the availability of orbital propellant depots, requiring an unspecified number of tanker missions for vehicle refueling. SpaceX asserts its Starship offers superior capacity, reusability, and cost-effectiveness for lunar exploration.

With NASA’s first lunar landing since the Apollo era only a few years away, the space agency has yet to determine exactly how its astronauts will reach the moon.

On Thursday, a NASA spokesperson told CNBC that both Blue Origin and SpaceX — which has been developing its Starship human landing system (HLS) for the mission, Artemis 3, since 2023 — have submitted revised landing architectures that could accelerate the agency’s timeline.

The spokesperson said NASA would extend its request for proposals to the broader space industry once the federal government reopens. A group of subject matter experts would then weigh in on the revised architectures.

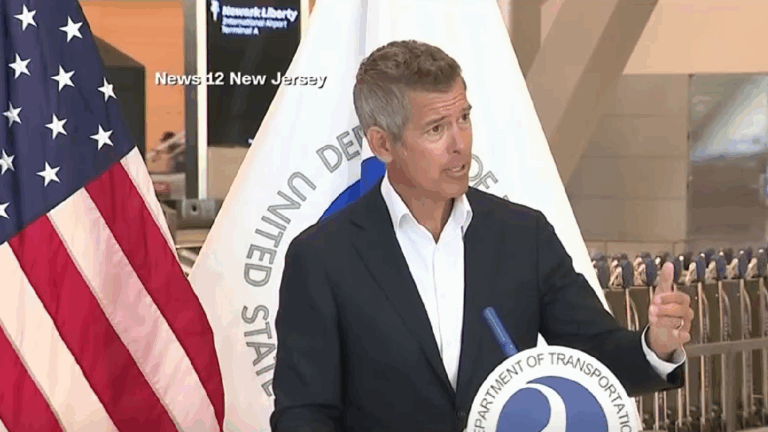

NASA in December 2024 forecast that Artemis 3 would launch in mid-2027. Though it has not officially modified that projection, interim NASA Administrator Sean Duffy last week appeared to place it in doubt, saying that the mission would fly a “couple years after” Artemis 2 in 2026.

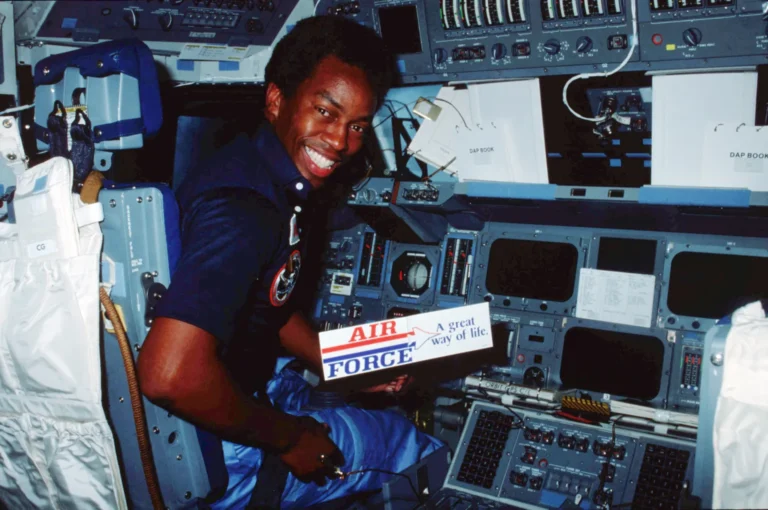

Duffy appeared on CNBC’s Squawk Box, during which he announced the reopening of the contract awarded to SpaceX and the Starship HLS. The latter was assigned to both Artemis 3 and a subsequent lunar landing, Artemis 4. If all HLS contract objectives are met, SpaceX stands to gain $4.5 billion.

About $2.7 billion of that money has already been paid out for hitting 49 milestones tied to the contract, the company said in a lengthy update on Thursday. Among them are demonstrations of the HLS life support, thermal control, docking, and landing systems. It also said it has begun building a flight-capable HLS cabin with functional systems that will be used for testing and crew training.

Not so fast…

Duffy last week said that SpaceX is “behind” on HLS development, opening the door for a competitor such as Blue Origin to step in. Blue has its own HLS contract to launch its Blue Moon Mark 2 (Mk2) lander on the Artemis V mission. It stands to win $3.4 billion if all milestones are met and has received about $835 million so far.

SpaceX’s gargantuan Starship rocket, around which Starship HLS is based, has completed 11 test flights, some more successful than others. It has demonstrated a few critical capabilities, such as the catch and reuse of multiple Super Heavy boosters. But more work is required for it to be human-rated, such as an orbital propellant transfer demonstration that was originally planned for this year and is now expected in 2026.

Blue Origin, meanwhile, has only completed one test flight of its New Glenn rocket, which will integrate with Blue Moon. But the company could send an uncrewed Blue Moon Mark 1 (Mk1) lander to the moon as soon as this year, Jacqueline Cortese, Blue Origin’s senior director of civil space, said this week.

Current plans call for both landers to be flown to lunar orbit before the Artemis 3 astronauts lift off in NASA’s Orion capsule, strapped to its Space Launch System (SLS) rocket. Orion and SLS would transport the crew to lunar orbit, where they would board the HLS and ride down to the surface of the lunar south pole. There, the lander would serve as an outpost for exploration.

Both companies’ plans rely on the availability of an orbital propellant depot, which would fuel up their vehicles on the way to the moon. Stocking that depot itself would require an unknown number of tanker missions.

Lunar duel

Blue Origin did not immediately respond to FLYING’s request for information about its Artemis 3 landing architecture. SpaceX, though, made its feelings about the renewed competition public.

“We’ve shared and are formally assessing a simplified mission architecture and concept of operations that we believe will result in a faster return to the Moon while simultaneously improving crew safety,” it said in Thursday’s update.

The company added that Starship is “singularly capable of carrying unparalleled numbers of explorers and the building blocks they’ll need to establish the first outposts on lunar and other planetary surfaces.” It also had the “highest technical and management ratings while being the lowest cost by a wide margin” among Artemis 3 HLS proposals, SpaceX said.

Per the company, Starship is “unmatched” as an Artemis 3 candidate due to its large size and reusability.

Starship HLS is projected to stand just over 50 meters tall, compared to Blue Moon Mk2’s height of about 15 meters. SpaceX has also demonstrated the reusability of Starship’s Super Heavy booster—a feat it hopes to replicate with the ship itself in 2026. New Glenn’s first stage is planned to be reusable, though Blue Origin has yet to prove it.

More work to be done

SpaceX said Starship’s development is “moving at a historically rapid pace.” It has produced more than three dozen ships and 600 Raptor engines. But it too has plenty left to prove.

The biggest test will be the orbital propellant transfer demonstration. Because Starship is so large, it will need to stop at an orbital depot to refuel before heading to lunar orbit. An unspecified number of Starship tanker variants will be used to stock it.

On the vehicle’s third test flight, SpaceX internally transferred about 5 metric tons of cryogenic liquid oxygen between tanks. Now, it must do so between ships.

An initial Starship will launch and spend an “extended time” on orbit to gauge how the vehicle performs and track any propellant boil-off. Then, a second ship will meet it on orbit for the transfer. The rendezvous will rely on DragonEye sensors that have docked SpaceX’s Dragon capsule to the International Space Station dozens of times. The sensors have undergone separate testing to evaluate their integration on Starship.

SpaceX on Thursday said the demonstration is targeted for 2026. But its timing will depend on the rollout of its Version 3 (V3) Starship.

The V3 is larger and more powerful than the rocket’s initial configuration and the Version 2 (V2) vehicles that flew this year. It will introduce larger propellant tanks, upgraded Raptor engines, and the ability to handle up to 150 metric tons of payload. It is also equipped with ports that will allow V3 ships to dock with one another.

Artemis 3 is not the only incentive for SpaceX to ramp up activities with the V3. The new variant is expected to be capable of orbital missions, including the launch of Starlink satellites and small telescopes. The company said it has invested billions of dollars into building five Starship launch pads across Texas and Florida. It also owns more than 5 million square feet of manufacturing and integration space.

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on FLYING