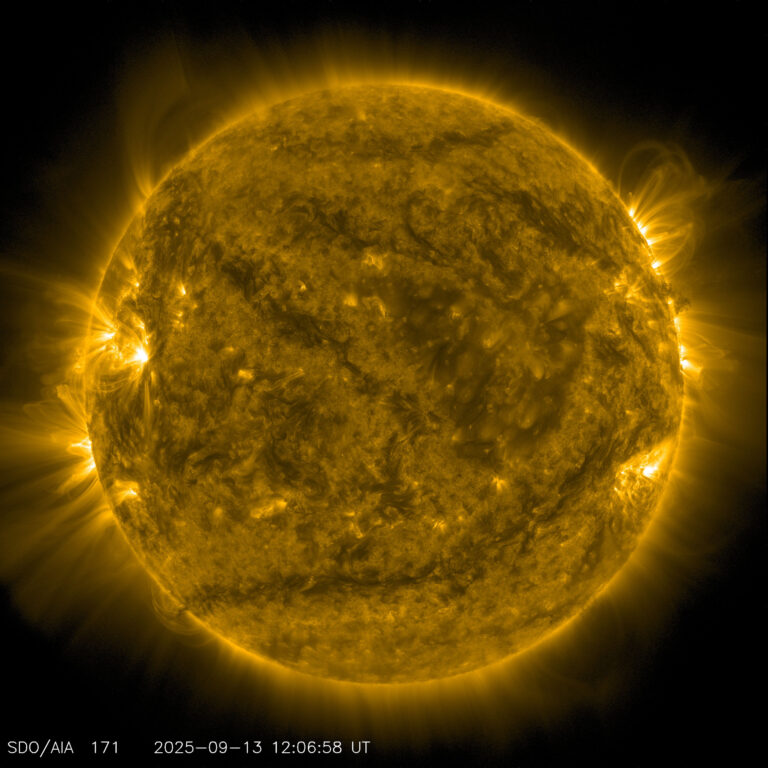

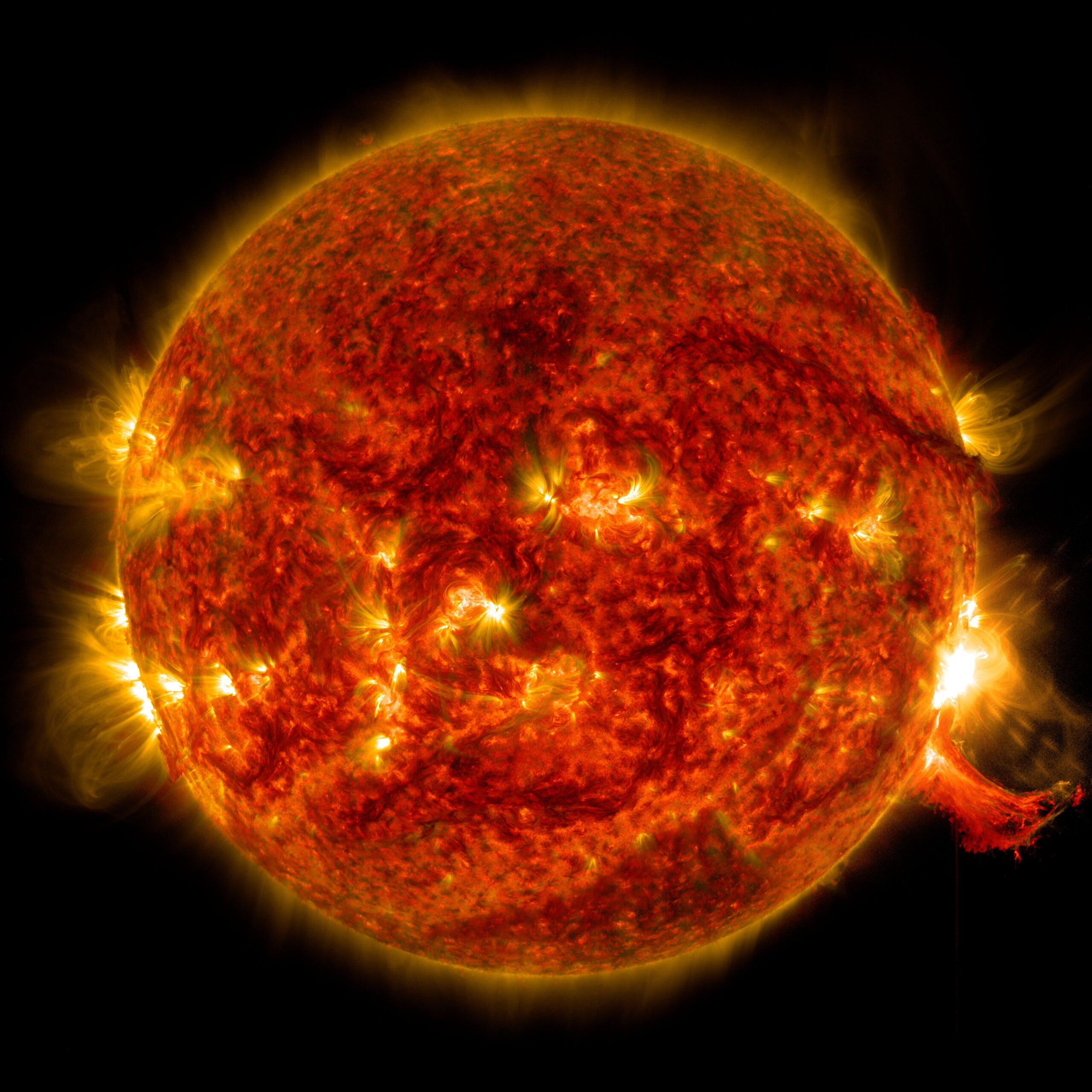

For the first time, scientists believe they have captured direct evidence of the mechanisms that trigger a solar flare. These massive explosions, generated by the Sun, release staggering amounts of electromagnetic radiation and often fling stellar material into space as coronal mass ejections.

While researchers have long understood that flares occur when energy is rapidly released from twisted magnetic fields reconnecting, the trigger that leads to this release remained elusive. Thanks to fortunately timed observations from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Solar Orbiter, researchers had a front-row seat to the precursor phase of a Sept. 30, 2025, flare. The findings from the observations were published on Jan. 21 in Astronomy & Astrophysics. It appears that solar flares behave a lot like avalanches: small, localized instabilities cascade into a massive release of energy.

“These minutes before the flare are extremely important, and Solar Orbiter gave us a window right into the foot of the flare where this avalanche process began,” said Pradeep Chitta, a physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research and lead author of the study, in a press release.

Magnetic reconnection

Flares release energy through a process called magnetic reconnection. Because plasma, like that in the sun’s corona, contains charged particles, it is threaded by magnetic field lines that can twist and tangle as the plasma moves. When two opposite magnetic field lines are drawn together, the lines can break apart and reconnect with the broken half of the other line. This reconnection event turns the magnetic field’s potential energy into kinetic energy, expelling the plasma. While the lines begin as parallel, the moment they break and reconnect, they form an “X” that slingshots the plasma outward like a rubber band.

A cascading effect

Based on observations from Solar Orbiter, Chitta and his team believe that a series of these reconnection events triggered a cascading effect, leading to increasingly larger expulsions of plasma and ultimately resulting in a solar flare.

To capture this process, researchers combined around 40 minutes of data from four of Solar Orbiter’s remote-sensing instruments. The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) provided high-resolution imagery of the corona, while the Spectrometer/Telescope for Imaging X-rays (STIX) tracked high-energy X-ray emissions, the fingerprints of highly accelerated particles. The Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument and the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) collected further data, allowing scientists to witness the flare’s evolution.

Just like an avalanche on Earth, the process starts slowly and then gains momentum. It begins with a complex X-like tangle of magnetic field lines connected to a rope-like filament of plasma. Every few seconds, new magnetic strands join the tangle, increasing the tension until the structure becomes unstable. As the field lines begin to break and reconnect, they trigger a flurry of activity which the paper describes as “initially weaker but rapid reconnection events.” Eventually, the chaos builds into large reconnection events which cause the filament to detach from the X-like tangle and unfurl into space, with bright reconnections firing all along its ropelike structure. This unfurling triggers the release of the main flare.

Raining plasma

As magnetic reconnection occurs (both before and during the flare), it accelerates particles toward the solar surface and outward into the solar system, reaching up to 50 percent the speed of light during the flare. When that magnetic energy hits the lower layers of the Sun’s atmosphere, it heats the plasma present. The plasma then rises, reaches the chromosphere, cools off, and falls back toward the solar surface in a phenomenon the researchers describe as “raining plasma blobs.” Importantly, this “rain” was observed both before, during, and after the peak of the flare. The pre-flare plasma blobs demonstrate that the environment was already being destabilized by smaller events, reinforcing the avalanche explanation.

“We really were in the right place at the right time,” Chitta said in the press release. Capturing this event was a feat of both engineering and luck. Because of limited observational windows and the massive amount of memory required to store the data, the spacecraft had to be perfectly positioned to catch such an event.

While the evidence from the Sept. 30 solar flare points to an avalanche-like trigger for a solar flare, it’s only one piece of evidence. More observations are required to know whether this model explains all solar flares.

“Solar Orbiter’s observations unveil the central engine of a flare and emphasise the crucial role of an avalanche-like magnetic energy release mechanism at work,” Miho Janvier, Solar Orbiter co-project scientist, explained in the press release. “An interesting prospect is whether this mechanism happens in all flares, and on other flaring stars.”