Today, most comets are found by robots. Wherever you are reading this, whatever time of the day or night it is, the unblinking electronic eyes of automated surveys like ATLAS or Pan-STARRS will be staring into the sky, seeking out these fascinating icy nomads. But legend tells of a time long ago, back in the golden days of astronomy, when actual human beings discovered comets visually, by peering into a telescope eyepiece and looking for tiny smudges that shouldn’t have been there.

In the late 1990s, there were no smart telescopes whirring in gardens while their owners watched TV from the comfort of their sofa. AI was just a science fiction cliche and phones were still attached to walls by coiled cords. And amateur astronomers with the patience and focus of a Jedi knight sat on stools in the dark, sweeping the sky with their telescopes, hoping to be the first person in history to see a chunk of ice left over from the birth of the solar system, 5 billion years earlier.

On one warm July night 30 years ago, two of them, at locations 330 miles (531 kilometers) apart, found a smudge that would go down in the history of astronomy as one of the most spectacular and beloved comets ever seen.

Discovery

On July 23, 1995, Alan Hale and Thomas Bopp were independently observing the same globular star cluster: M70, a smoky ball of ancient stars in the constellation Sagittarius the Archer. Experienced observers, both knew the sky well, but as they looked at the familiar cluster, they each noticed a faint smudge close to it that they didn’t recognize and which wasn’t on any of their charts.

After tracking the interloper’s movement through the star field for a short time, both suspected it was a new comet. Within hours of each other, they had notified the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams (CBAT) — the clearinghouse for reporting new astronomical findings — of their observations. Soon after, the object was confirmed as a new comet and officially designated C/1995 O1. Because of their simultaneous discoveries, it was named Comet Hale-Bopp.

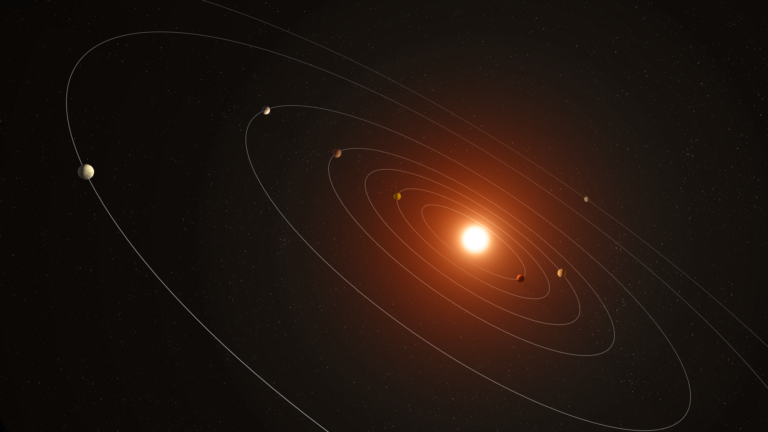

Comet Hale-Bopp was just a magnitude 10.5 out-of-focus star when the two amateurs found it. Most comets are discovered when they are relatively near the Sun, but at the time of its discovery Hale-Bopp was ridiculously far away — more than 7 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun, and roughly 670 million miles (1.1 billion km) from Earth. (One AU is the average distance between Earth and the Sun, or 93 million miles [150 million km].)

Hoping for a bright one

The fact that it was already 10th magnitude while still so far away was exciting for two reasons. First, it suggested that the comet’s nucleus was big. (Later estimates suggested its nucleus was 25 to 37 miles (40 to 60 km) wide, far larger than the average comet.) Second, it meant that Hale-Bopp had the potential to be a bright naked-eye comet when it came close to the Sun in two years’ time – perhaps one of the brightest for many years.

Compared to the online feeding frenzy that accompanies the discovery of even a potential naked-eye comet these days, the build-up to the arrival of Comet Hale-Bopp was restrained. With no social media to breathlessly spread hype and misinformation, the comet was written about with careful optimism in monthly astronomy magazines and newspaper features. But as the comet continued to brighten, it was confidently predicted to be the “Comet of the Century” and excitement levels began to rise, even as the ghost of Comet Kohoutek — a comet that was predicted to be bright in 1973, but wasn’t — rattled its chains and chuckled in the background.

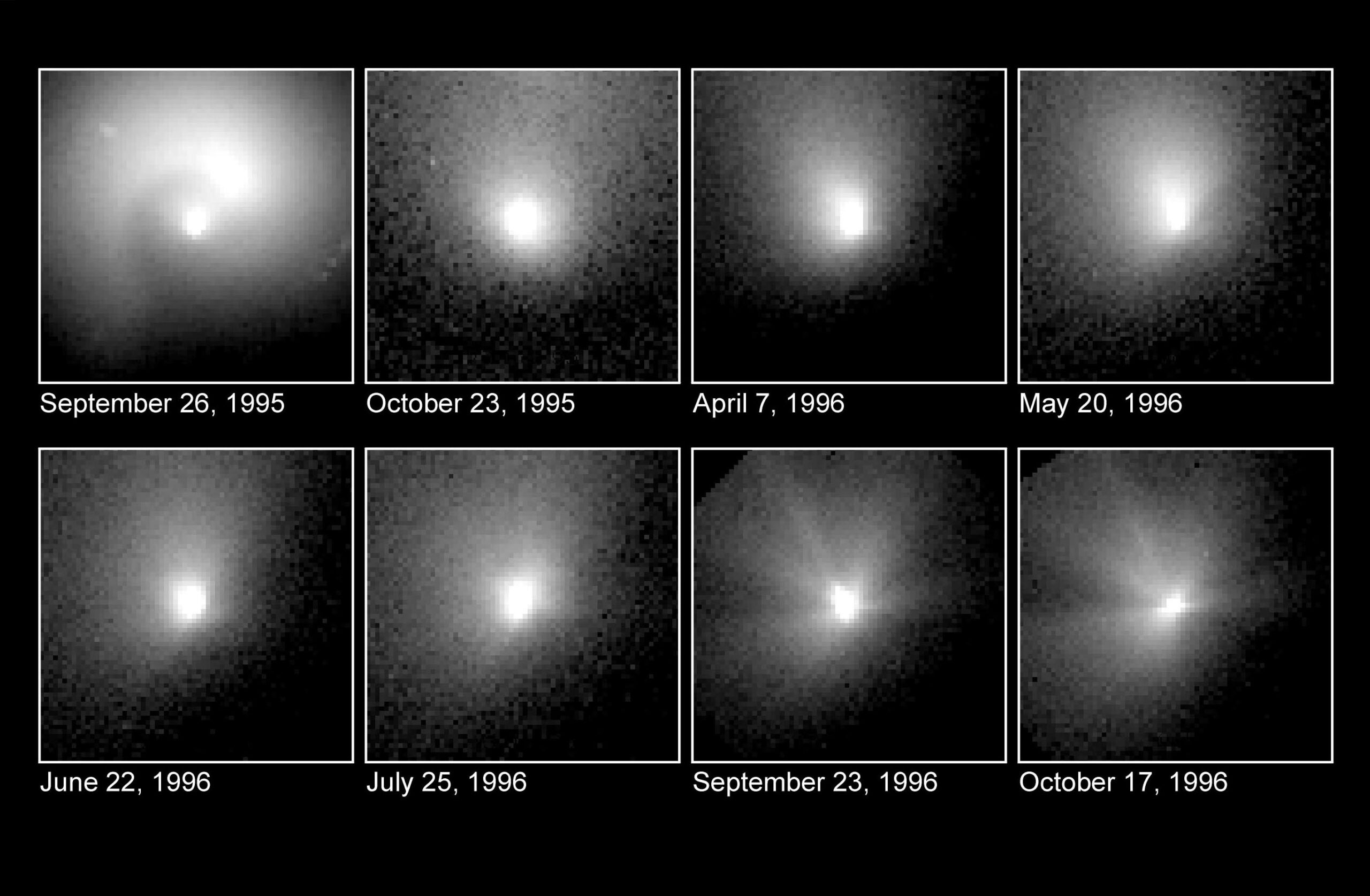

Getting brighter

Hale-Bopp remained at 10th magnitude for a long time after its discovery, crawling slowly through Sagittarius. By the spring of 1996, though, it had begun to brighten rapidly. As April of that year began, it glowed at 8th magnitude, visible in binoculars and small telescopes at dark sites, not far from Jupiter in the sky — a good comet, certainly; one of the brightest of the year, definitely; but still a sight reserved for amateur astronomers who had the equipment and knowledge of the night sky needed to find it.

By mid-July the comet had brightened to 6th magnitude, and this was when many people saw it for the first time. At magnitude 6, Hale-Bopp was technically visible to the naked eye for people at dark locations who knew exactly where to look. Most people, however, still needed binoculars to see it because it was embedded in the frothy star clouds of the Milky Way. I had my first sighting on July 11, scanning the Milky Way from my garden through binoculars — or so I thought. In fact, I mistook the nearby Wild Duck Cluster (M11) for the comet and didn’t see the comet itself for another couple of nights.

By the time the first Perseid meteors were skipping across the August sky, Hale-Bopp had moved into Ophiuchus and had reached 5th magnitude, brightening steadily. As October began, the comet, now a 4th-magnitude object, approached and passed the beautiful globular star cluster M14. Things were definitely getting interesting.

Christmas and New Year’s came and went with no sign of the comet fading or falling apart. As February ended, with Hale-Bopp shining brightly in both the morning and evening sky, amateur astronomers allowed themselves to get excited, daring to believe that after many disappointments perhaps the long wait for a Great Comet, like those recorded in paintings and on wood carvings in centuries past, was finally coming to an end.

A Great Comet

By mid-March, with perihelion — the comet’s closest approach to the Sun — just weeks away, Hale-Bopp was a hypnotizing sight, 1st magnitude in brightness and visible all through the night for observers at mid-northern latitudes.

I viewed it every chance I got. In the evenings, I watched it from parks close to my home, and I showed it to many excited members of the public. And in the mornings, before going to work, I trekked a mile out of town in the dark to view and photograph it from a secluded farm far from light pollution. Describing those predawn views of its bright head and twin tails as magical doesn’t come close to doing it justice.

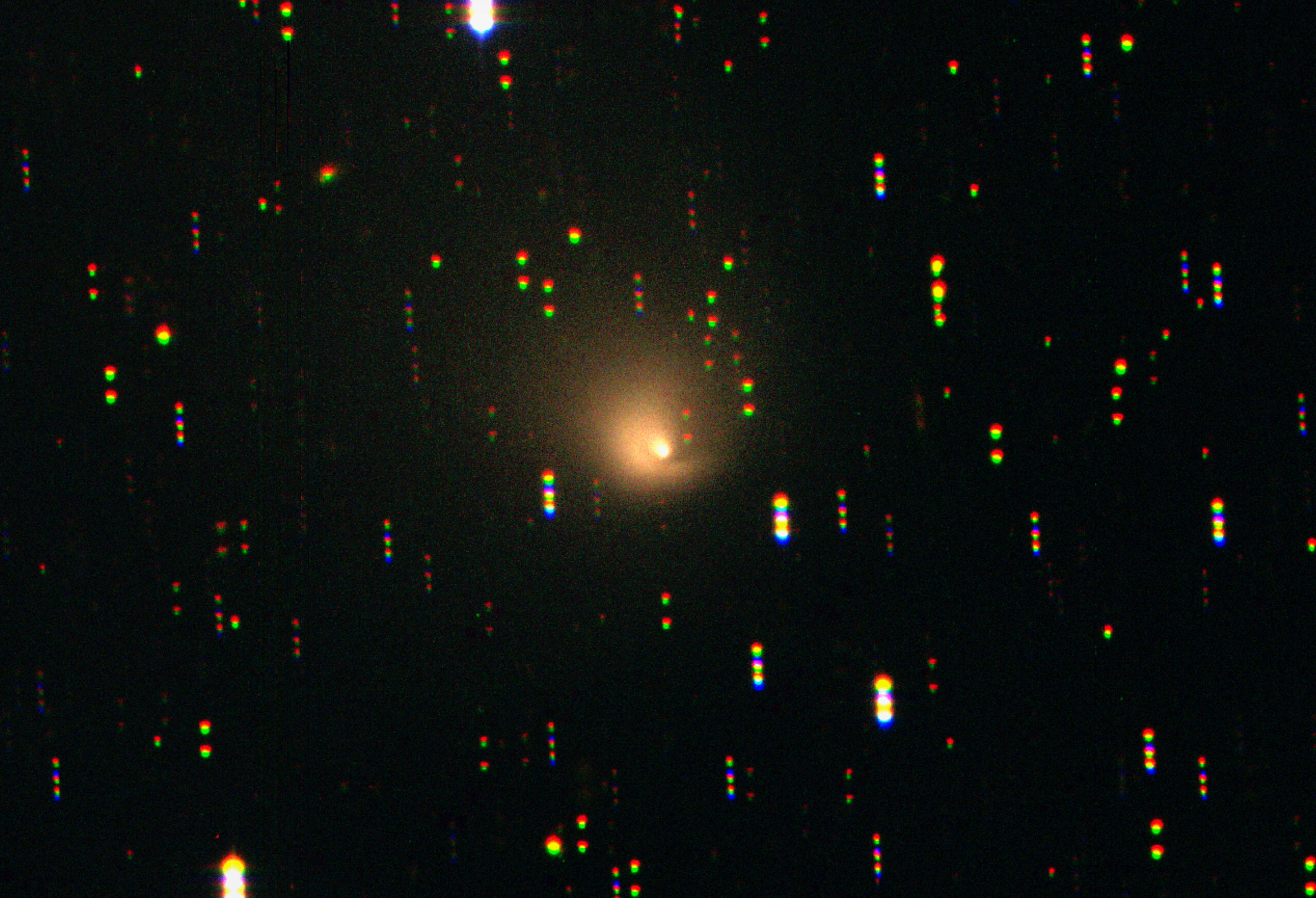

March and April of 1997, when the comet whooshed toward and then around the Sun, were when most people saw the comet. Now blazing at magnitude –1.5 or brighter beneath the stars of Perseus and Cassiopeia, it was such a stunning sight in the evening sky that people simply stopped to stare at it as it emerged from evening twilight.

It was visible as a ghostly streak of light before the first stars appeared, and as the sky darkened it was so bright that even non-astronomers with no prior knowledge of the sky could find it just by looking west: There it was, right before their eyes, its long, straight blue gas tail and elegantly curved dust tail painted on the sky by some celestial artist.

Here in the U.K., the comet’s slow drift across the spring sky coincided with a long spell of unusually clear weather, so night after night we went out to see it. By then it had become a familiar sight, almost as much a feature of the night sky as the Big Dipper. People became used to seeing it in the sky as they packed groceries into their cars after work or walked their dogs after dinner.

The comet was all over the news too. Newspapers printed finder charts for their readers, while TV meteorologists told viewers where to look for it in the sky. Hale-Bopp had become a celestial celebrity, one of the most widely observed comets for many, many years.

Meanwhile, amateur astronomers were gazing at the comet through their telescopes and marveling at the view. Under even modest magnification they could see bright jets and plumes coming off the starlike nucleus, which itself was surrounded by ghostly shells and spirals of material. With binoculars they swept their gaze down the length of the long tails, wondering at the sight of streamers and ribbons of dust and gas within them.

By the beginning of May, the “Greatest Show in the Night Sky” was winding down. Hale-Bopp had faded to “just” 0 magnitude, and it began to slip out of the headlines and weather reports. But it remained visible in the sky for weeks, slowly fading until it was eventually lost from view.

I remember how, when it did disappear, many amateur astronomers felt conflicting emotions. On one hand, we were glad that we had seen something so special. But there was another part of us that felt like the night sky had become darker, that something precious had been stolen from it. I think we knew we would probably never see something like it again in our lives, and that hurt.

Today, Hale-Bopp is part of history. It was a Great Comet, rivalling those seen in centuries past, and it delighted millions of people. Many thousands of photos were taken of it around the world in the spring of 1997 — on expensive 24- or 36-exposure slide and print film, not today’s cheap memory cards that can store thousands of images — but none of them come anywhere near capturing how lovely the comet was, or how it felt to stand there in silence, on those balmy March and April evenings, just staring at it as it shone in the sky like a visitor from another universe much more beautiful than our own.