Scientists are shining a brighter light on dark matter thanks to a new high-resolution map, unveiling the invisible material that shapes everything we see.

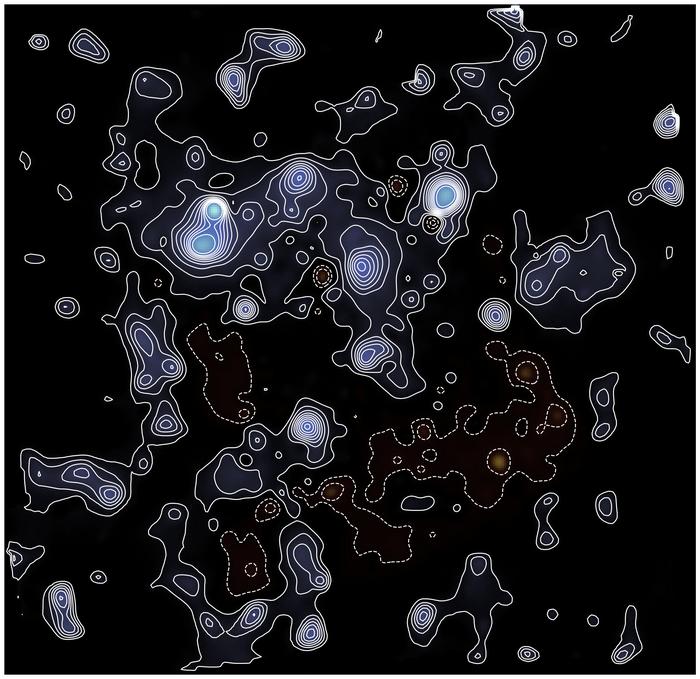

Using James Webb Space Telescope’s (JWST) imaging from the COSMOS-Web survey, a team of researchers created a high-resolution map of the universe’s dark matter over a contiguous 0.54-square-degree area of the sky — the largest map of its kind. The new map, created by looking at how the gravity from this invisible matter warps space around it, has twice the detail of its predecessors, revealing galaxy clusters, strands of dark matter, and even hidden faint galaxy groups that were previously unseen. The team’s findings were published Jan. 26 in Nature Astronomy.

“The map shows the dark matter backbone of the universe in much finer detail than ever before in the COSMOS-Web field,” Diana Scognamiglio, a cosmologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and co-lead author of the study, tells Astronomy. “It reveals where dark matter is concentrated in galaxy clusters, how those clusters are connected, and where large empty regions lie. For the first time over a wide area, we can see the small-scale structure of the cosmic web and even detect mass concentrations that were not visible in earlier maps.”

How to see in the dark

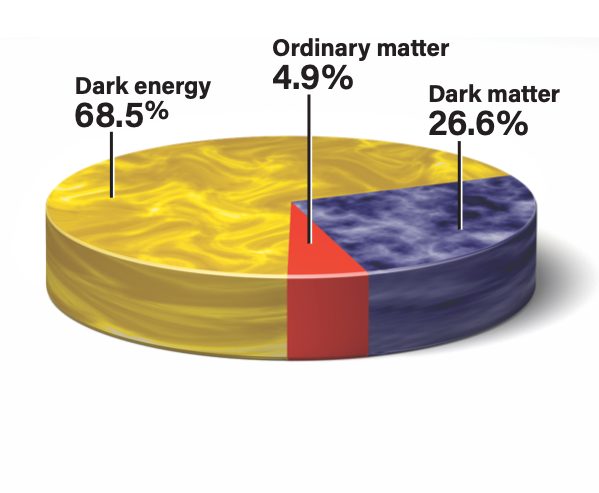

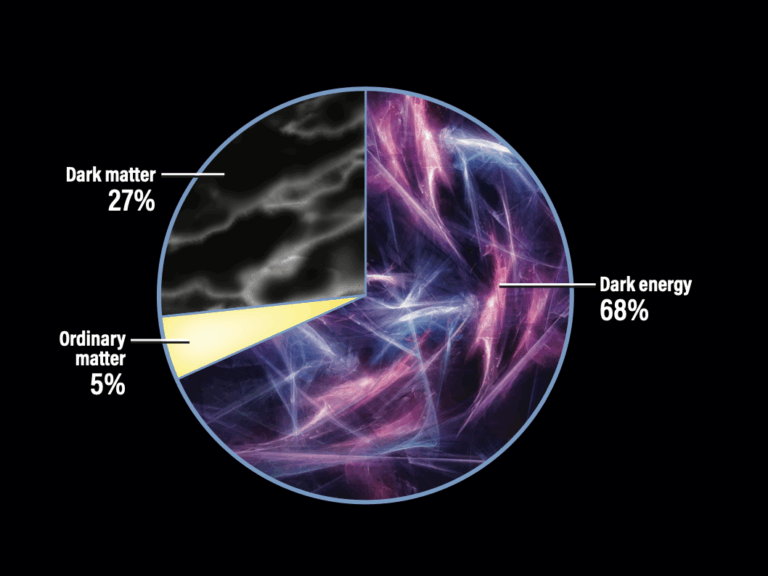

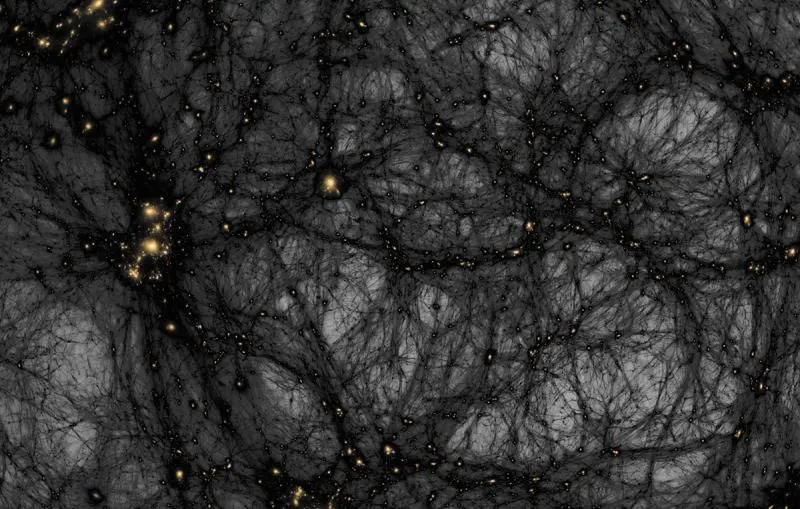

According to the current standard cosmological model, called Lambda-CDM or ΛCDM, dark matter accounts for around 85 percent of the universe’s matter and serves as its scaffolding. Its gravitational pull influences where the normal matter in our universe congregates and can even hold its structures together. “[T]he whole swirling cloud of dark matter around the Milky Way has enough gravity to hold our entire galaxy together. Without dark matter, the Milky Way would spin itself apart,” Richard Massey, co-author and cosmologist at Durham University, said in a press release.

But because it does not emit or absorb light, dark matter is invisible to conventional telescopes. To locate dark matter, scientists can instead use a technique called weak gravitational lensing. Gravitational lensing occurs when the light from a distant source encounters a source of mass between it and observers here on Earth. The gravity of this intervening mass bends and amplifies the light from the background source, which then appears warped to the observer. The amount of lensing depends on the intervening mass.

In strong gravitational lensing, the light is bent significantly, resulting in unique phenomena like arcs and rings. In weak lensing, the distortion is much smaller, instead only warping the image slightly. If scientists measure that slight distortion, they can measure the intervening mass — even if they can’t see it. And if they can measure distortion effects in objects across the sky — say, in the shapes of background galaxies — they can create maps of the unseen matter: dark matter.

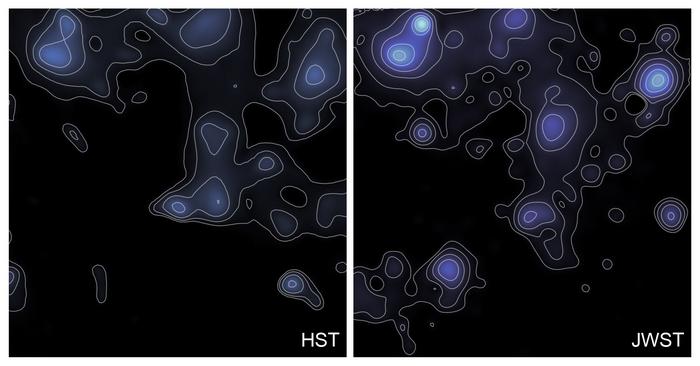

So, the more galaxies you resolve, the more dark matter you map.

Earlier maps of dark matter relied on observations of galaxies from ground-based telescopes or the Hubble Space Telescope. Ground-based telescopes are limited in how sharp a view of the sky they can achieve due to the blurring effects of Earth’s atmosphere, typically resolving the shapes of less than 20 galaxies per square arcminute (one degree of the sky contains 60 arcminutes; one square degree of sky contains 3,600 square arcminutes). Observing from above the atmosphere, Hubble can resolve about 71 galaxies per square arcminute. But both options pale in comparison to JWST, which can resolve around 129 galaxies per square arcminute.

Bridges and nodes

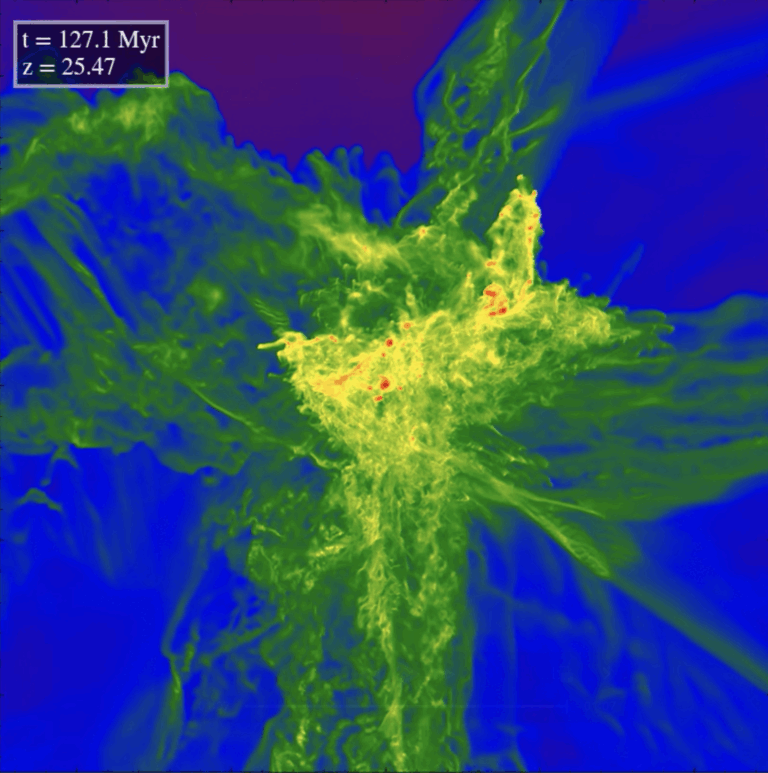

The new JWST map results from the measurement of around 250,000 galaxies within a region of sky 0.54 square degrees in size. It reveals a complex map that includes a network of filamentary bridgelike features stretching between galaxy clusters. These strands of dark matter appear to act as a skeletal system along which gas and galaxies are distributed. The map also identified never-before-seen low-mass galaxy groups that were too far or too faint to identify with other telescopes.

“Filaments are like the strands of a giant cosmic spider web. The thick knots in the web are galaxy clusters, and the strands between them are filaments. In the ΛCDM model, dark matter collapses under gravity to form this web, and ordinary matter — gas and galaxies — follows along these filaments,” Scognamiglio says.

RELATED: What is the cosmic web made of?

“The map is a two-dimensional image of the projected total mass distribution on the sky, derived from the shapes of background galaxies. It tells us where in space the dark matter is distributed,” Scognamiglio says. According to ΛCDM, galaxies form at what Scognamiglio calls “thick knots” or nodes along the filaments of dark matter. And this is precisely what the new map seems to show, reinforcing one of ΛCDM’s main predictions about the nature of dark matter.

Setting a new standard

The new map’s unprecedented detail and resolution offer a window into the evolution of galaxies and dark matter filaments some 8 billion to 11 billion years ago — farther back than previously observed, offering insight into how these structures influenced each other during the peak era of star formation in our universe.

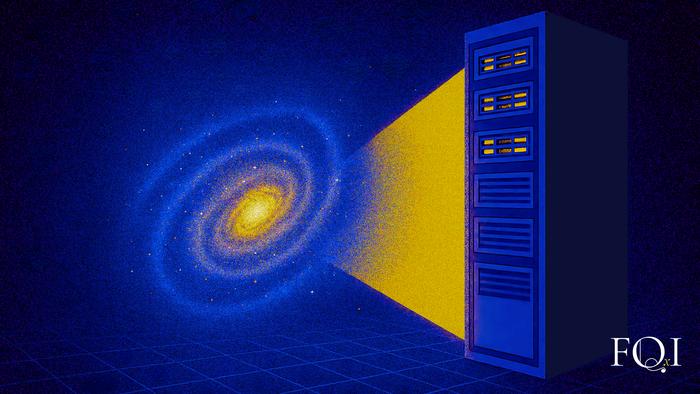

By providing this level of clarity, the map sets a new benchmark against which all future theories and simulations can now be measured. “It allows theorists and observers to directly compare detailed predictions from cosmological simulations with real data, helping to test how well our models describe the growth of structure and to search for subtle deviations that could point, who knows, to new physics,” Scognamiglio says.

While this new map offers an unprecedented look at dark matter, it only covers a small portion of the sky. But, according to Scognamiglio, it is only the beginning.

“While JWST provides an ultra-high-resolution view over a relatively small area, future and upcoming missions like ESA’s Euclid and NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will apply similar weak lensing methods over much larger regions of the sky,” Scognamiglio notes. “Together, these surveys will allow us to map dark matter across a large fraction of the universe, moving from detailed case studies to a truly global view of the cosmic web.”