Elon Musk’s merger of SpaceX and xAI — his artificial intelligence (AI) company best known for its chatbot Grok — is a bid to help realize his latest ambition: a constellation of orbital data centers powered by the Sun.

On Jan. 30, SpaceX filed with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for approval to launch up to 1 million satellites for a megaconstellation of orbital data centers. Then, on Feb. 2, Musk announced the largest merger in history, valued at $1.25 trillion according to Bloomberg. Through vertical integration of the two companies’ capabilities, Musk hopes to put solar-powered data centers in space, bypassing Earth’s energy constraints and providing AI access to the masses at reduced cost.

“In the long term, space-based AI is obviously the only way to scale. To harness even a millionth of our Sun’s energy would require over a million times more energy than our civilization currently uses!” Musk explained in the press release announcing the merger.

At present, the future of Musk’s new megaconstellation is in the hands of the FCC. On Feb. 4, the organization opened the filing for public comment, initiating a review process that will determine the project’s fate. The FCC serves as the gatekeeper for U.S. commercial space operations; without FCC approval, Musk’s constellation won’t leave the ground.

The rising cost of data centers

Data centers are secure facilities housing technological infrastructure, like central processing units (CPUs). In the early days of computing, these were often specialized rooms containing a single, massive mainframe computer used for basic calculations. The internet era shifted the focus as facilities grew into large warehouses filled with rows of servers to host websites, email, and cloud-based services for millions of users. Now, AI is driving a shift to even greater scales. For example, Meta’s Hyperion in Louisiana will span nine buildings and 4 million square feet. These AI data centers rely on graphics processing units (GPUs) to train and operate complex AI models. Unlike CPUs that process tasks individually, GPUs handle many calculations at once, providing the speed necessary for AI.

The environmental cost of operating AI data centers is no secret. In 2024, the U.S. consumed more electricity than in any other year — around 4,405 terawatt-hours (TWh). According to the Pew Research Center, data centers consumed 183 TWhs of that energy, or roughly 4 percent of U.S. electricity — a figure that could triple by 2030. Data centers also have an enormous thirst for water. A hyperscale facility (a large data center comprising an entire building or buildings) now consumes up to 5 million gallons of water daily for cooling — enough to supply a town of up to 50,000 people. This strain on Earth’s limited resources is only set to worsen.

Big tech eyes orbital data centers

While putting a data center in space might sound like science fiction, Musk is hardly alone in his conviction; Silicon Valley’s heaviest hitters have all recently signaled that off-planet computing is on the horizon. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman mused during his July 2025 appearance on comedian Theo Von’s This Past Weekend podcast that while “tiling” Earth with servers is a short-term fix, data centers in space might be the long-term solution. Jeff Bezos went further in October while speaking at Italian Tech Week, predicting “giant gigawatt data centers in space” within 20 years, arguing they will eventually beat terrestrial costs. Even former Google CEO Eric Schmidt placed his bet by acquiring rocket manufacturer Relativity Space — a move he confirmed on X was at least related to a play for orbital data centers.

Launching a million satellites won’t be cheap, even though launch costs have been decreasing over the last decade. However, outer space offers access to continuous solar energy. Advocates say that after initial launch costs, the overhead to run an orbital data center would be incredibly low compared to its terrestrial counterparts, with no need to pay energy or water bills.

A few problems

Critics, however, argue that space-based data centers face a series of challenges — chiefly the issue of cooling. On Earth, servers are cooled by air or water, but space is a vacuum. Without air to carry heat away, a several-hundred-megawatt server would quickly melt unless equipped with radiators to emit waste heat. In theory, this is nothing new. All spacecraft use radiators to dissipate waste heat. The issue with orbital data centers is that the sheer amount of heat would require radiators much larger than any built before. The largest radiators in space are part of the International Space Station’s (ISS) External Active Thermal Control System (EATCS), which uses 14 six-by-ten-foot radiator panels to expel a measly 70 kilowatts (kw) of waste heat at any given time. A several-hundred-megawatt data center would be generating thousands of times more heat than the ISS, requiring a radiator thousands of times larger than those in the EATCS. Building, launching, and assembling a radiator in space that large is a task that has not yet been demonstrated — and its sheer size would significantly add to launch costs. In addition to the cooling issue, data centers in space would have to be hardened against the effects of radiation, adding further to the cost and payload size. Plus, it’s a lot harder to service damaged hardware in orbit than on the ground.

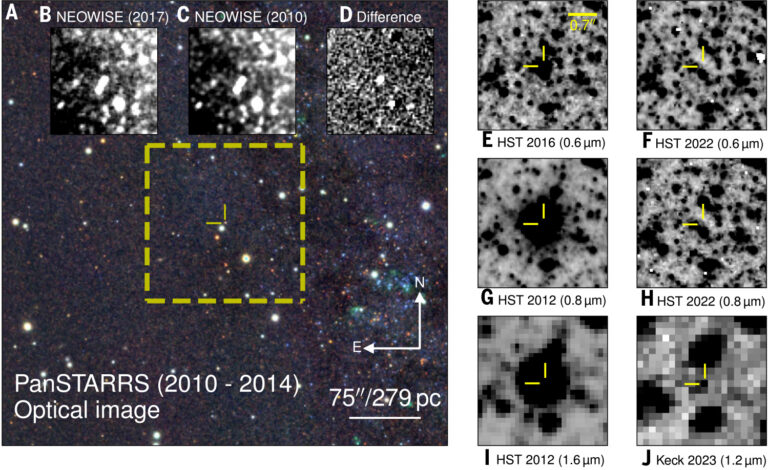

There are also environmental and safety concerns. Adding even more megaconstellations to an already congested low Earth orbit (LEO) could ruin the night sky and endanger lives on the ground. There are over 15,000 satellites already in orbit, and that number could hit half a million by the late 2030s. A recent report in Nature warns that such proliferation of megaconstellations would interfere not only with ground-based astronomy, but space observatories as well: The Hubble Space Telescope could have one-third of its observations potentially contaminated in the coming years. For NASA’s SPHEREx mission, the outlook is bleaker: Up to 96 percent of its images could be ruined by the streaks of passing hardware.

Beyond ruined images, the physical danger is escalating. As these disposable satellites reach the end of their short lifespans, they must de-orbit and burn up. A 2023 FAA report estimated that by 2035, the sheer volume of falling debris could result in one person being killed every two years. Furthermore, the impact of this strategy on Earth’s atmosphere is largely unknown. Research indicates that re-entering satellites could deposit much more aluminum into Earth’s upper atmosphere than meteoroids naturally do. This could alter how reflective Earth is (its albedo), changing how much of the Sun’s energy makes its way to Earth and shifting global temperatures. The increasing launch cadence could also damage the ozone layer and increase CO2 emissions.

Small steps for AI

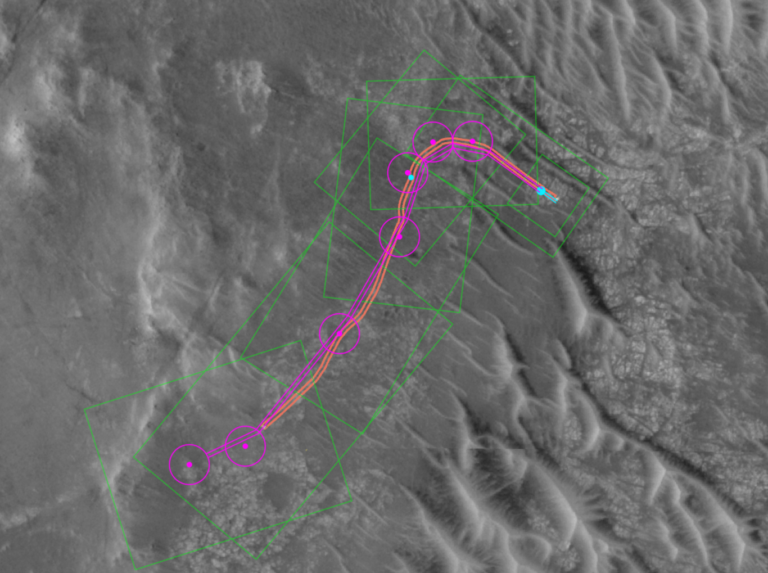

Despite these hurdles, the race has already begun with smaller, proof-of-concept missions. Florida-based company Lonestar Data Holdings sent a relatively small 8-terabyte (TB) data center called Freedom on a mission to the moon aboard Intuitive Machines’ Athena lander in early 2025. (As a point of comparison, large data centers contain exabytes of storage, and one exabyte contains 1 million TBs.) Freedom was designed for data storage and recovery, not complex processing. While Athena didn’t survive the lunar landing, Freedom was able to successfully send, receive, and manipulate data en route to the moon and briefly on the lunar surface.

In May 2025, China launched the first dozen satellites of its planned 2,800 satellite constellation known as the Three-Body Computing Constellation. Planned to be a supercomputer in space, each of the dozen satellites will be linked by laser communications. The entire constellation, once completed, will be capable of completing 1,000 peta operations per second (POPS). For comparison, a single NVIDIA H100 GPU completes around 0.06 POPS, meaning you’d need over 1500 GPUs to reach the constellation’s computing power. Still, a hyperscale AI data center can contain tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of GPUs. So while the Three-Body Computing Constellation will be a lightning-fast supercomputer, it won’t come close to the processing power of an earthbound AI data center.

In early 2026, the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) announced a new space initiative called “space+,” which includes, along with a push for space tourism and debris remediation, plans for “giga-watt level space infrastructure,” designed to support “space-based data processing” as reported by China Global Television Network.

Additionally, the startup Starcloud, backed by U.S. chipmaker Nvidia, launched Starcloud-1, a fridge-sized satellite carrying a high-powered NVIDIA H100 GPU in November 2025. Equipped with a processor 100 times more powerful than traditional space-qualified hardware, Starcloud-1 was able to train and operate the OpenAI language model NanoGPT and also get responses from Google’s language model Gemma.

These are small steps, to be sure, but these successes might just pave the way for the megaconstellations Musk and others now intend to build.