Key Takeaways:

- January presents optimal viewing conditions for Jupiter, which reaches opposition on the 10th in Gemini at magnitude -2.7, offering its largest apparent diameter (47") and opportunities to observe atmospheric details and its four bright moons. Saturn, at magnitude 1.0, is positioned in the western sky, transiting into Pisces, with its 17" disk and 38" ring system remaining telescopically observable.

- The inner planets, Venus, Mars, and Mercury, will be unobservable throughout January due to their respective superior conjunctions with the Sun on the 6th, 9th, and 21st. Additionally, a lunar occultation of the first-magnitude star Antares is predicted for January 15th, visible from specific regions of Australia.

- The article features the open cluster NGC 2360, also known as Caroline's Cluster, located 8° east of Sirius in Canis Major. This 2.2-billion-year-old cluster, with a total magnitude of 7.2, was discovered by Caroline Herschel in 1783 and is detectable with binoculars under dark sky conditions.

- Prominent constellations like Orion and Canis Major rise higher in the January evening sky, providing numerous deep-sky targets. An accompanying star map, configured for observers at approximately 30° south latitude, indicates sky appearance at specific times across the month.

As the new year dawns, the solar system’s two largest planets put on fine shows in the evening sky.

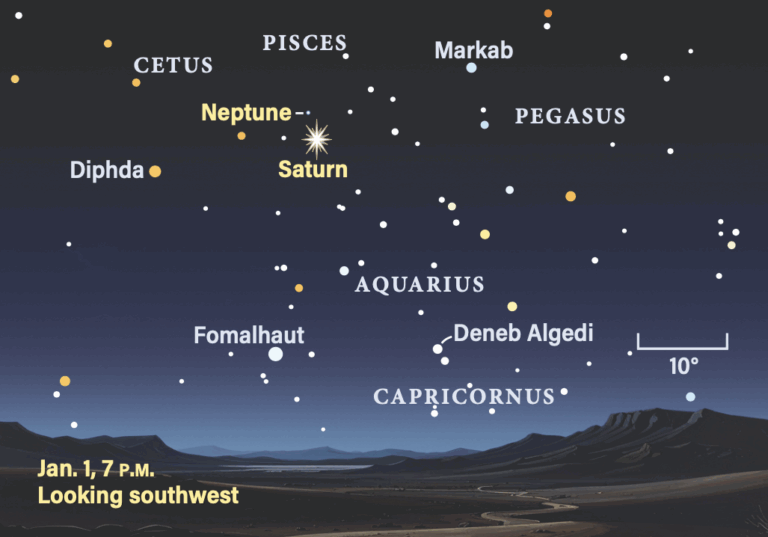

Saturn continues to dominate the western stage. It glows at magnitude 1.0 against the backdrop along the Aquarius-Pisces border. It officially leaves the Water-bearer in the middle of January and enters the Fish for what will be a short three-month stay.

Saturn’s sluggish eastward slide relative to the background stars is no match for the Sun’s more rapid motion, which means the ringed planet dips closer to the horizon with each passing day. You’ll want to turn your telescope toward Saturn in the early evening while it remains fairly high. The planet shows a disk measuring 17″ across the equator surrounded by a ring system that spans 38″ and tips 1.4° to our line of sight. The narrow tilt reduces glare enough that you should be able to see Saturn’s brightest moons — Titan, Dione, Rhea, and Tethys — easily through a 10-centimeter instrument.

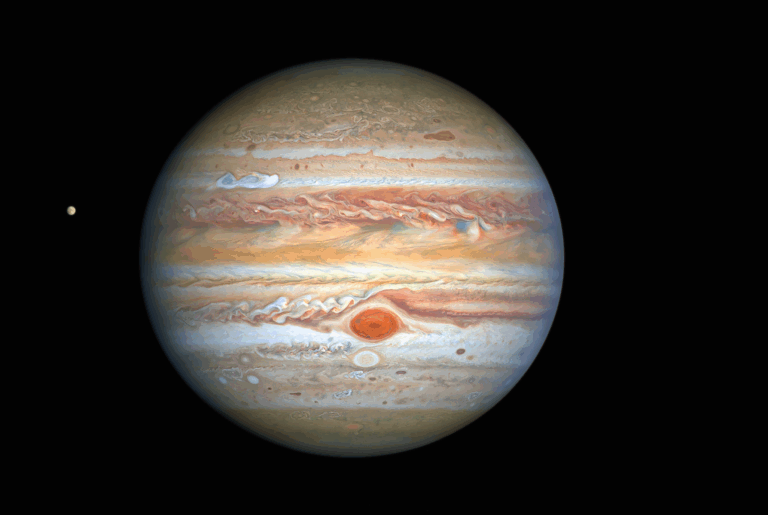

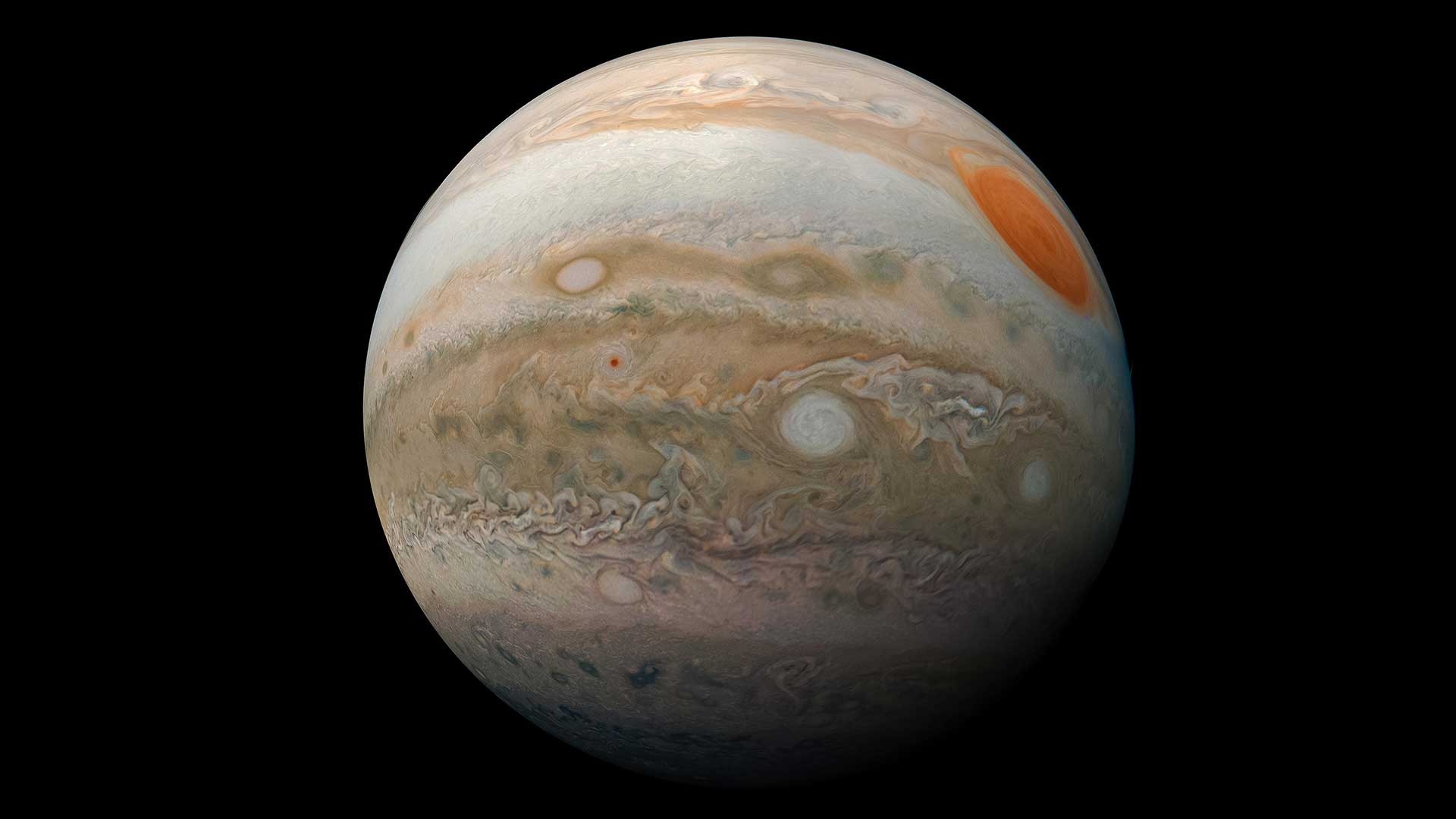

As nice as Saturn looks, Jupiter takes over showpiece status this month. The giant planet reaches opposition Jan. 10 among the stars of Gemini. Opposition means the planet rises at sunset and sets at sunrise, and marks its closest approach to Earth for the year. It also achieves peak brightness at opposition, gleaming at magnitude –2.7. Shining like a beacon, Jupiter often causes people to mistake it for an airplane’s landing light.

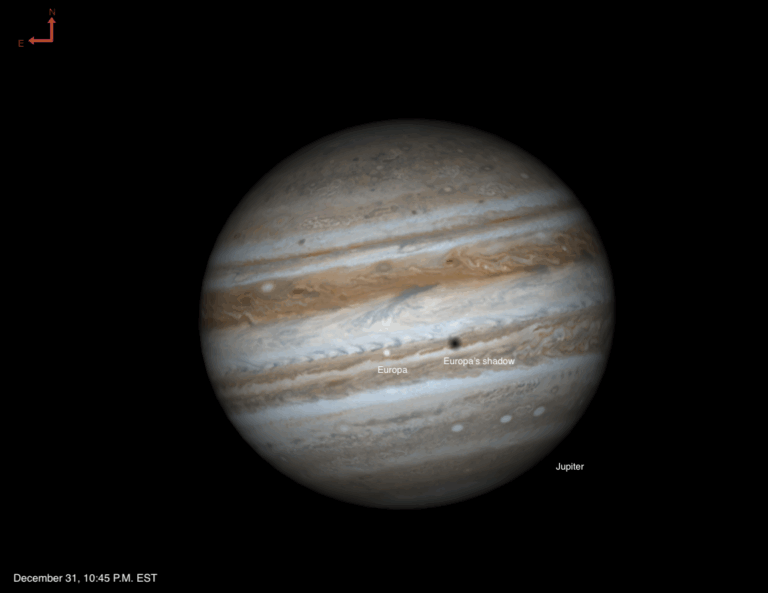

As you might guess, Jupiter looms largest through a telescope at opposition. Its equatorial diameter maxes out at 47″, big enough to show lots of atmospheric detail. Look for a bright zone that coincides with the gas giant’s equator flanked by two darker belts. In moments of good seeing, you should see a series of alternating zones and belts. And any scope also reveals Jupiter’s four bright moons. Because the planet currently lies well north of the celestial equator, the best views come within an hour or two of local midnight when it stands highest in the sky.

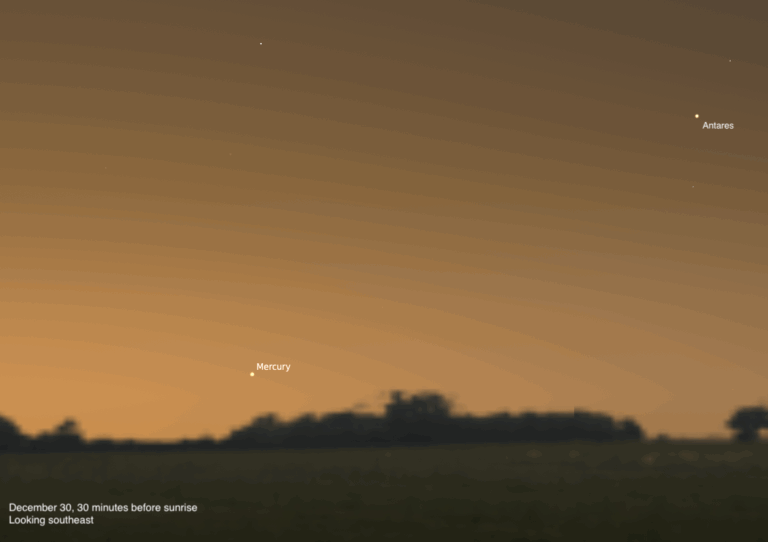

Sadly, the other three naked-eye planets remain out of sight all month. Venus, typically a brilliant sight in the morning or evening sky, reaches superior conjunction Jan. 6. Mars is in conjunction with the Sun just three days later. And then, as if to mimic Venus, Mercury arrives at superior conjunction Jan. 21.

People sometimes ask me why we use the terms “superior” and “inferior” for some planetary conjunctions with the Sun. It seems scientists first used the term “superior conjunction” in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in 1716 to describe the appearance a planet would have (if it were visible) when it passes on the far side of the Sun as seen from Earth. Today, astronomers only use the terms for the inner planets, Mercury and Venus.

A waning crescent Moon occults the 1st-magnitude star Antares in the early morning hours of Jan. 15 for observers across much of Australia (except for most of Queensland). From Adelaide, South Australia, Antares disappears behind the Moon’s bright limb at 18h11m UT (on the 14th in Universal Time) and reappears at 19h11m UT, near the start of twilight.

The starry sky

As January progresses, the magnificent collection of bright stars in Orion and Canis Major appears higher in the sky at the same time each evening. The two constellations hold many intriguing deep-sky objects, but first I want you to take a few moments to simply identify their familiar shapes with the unaided eye. These star patterns were among the first I learned to spot as I was growing up in Tasmania. I always felt that the part of the Big Dog southeast of Sirius looks like a coathanger without a hook, like those so often found in hotel rooms these days.

Canis Major has many attractions — the open clusters M41 and NGC 2362 rank high on many observing lists — but I want to focus on an often overlooked one located 8° east of Sirius: open cluster NGC 2360. Caroline Herschel (1750–1848) discovered this cluster in 1783. She was the sister of the famous astronomer William Herschel (1738–1822), who discovered Uranus in 1781.

Caroline moved from Germany to England in 1772 to join her brother in Bath, where she became an astronomer in her own right. She initially assisted William by recording his observations, and King George III granted her payment for this work. She discovered eight comets beginning in 1786. Before then, however, she first spotted an open cluster about 3° east of the 4th-magnitude star Gamma (γ) Canis Majoris on the night of Feb. 26, 1783. It became number 2360 in the New General Catalogue (NGC), and would become known as Caroline’s Cluster.

With a total magnitude of 7.2, Caroline’s Cluster shows up in binoculars as a tiny patch of light under a dark sky. I find this a fairly difficult find thanks to a distracting 6th-magnitude star just to the west.

If you don’t have an equatorial or go-to mount, a good way to find the cluster is to center Gamma CMa in the field of a low-power eyepiece and wait about 14 minutes for Earth’s rotation to carry the cluster into view. The cluster appears as a patch of light at first impression, but turns into a delightful little bunch of stars on closer inspection. Its brightest member glows at magnitude 8.9.

NGC 2360 is quite old for an open cluster. Astronomers estimate its age at around 2.2 billion years.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 30° south latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

11 p.m. January 1

10 p.m. January 15

9 p.m. January 31

Planets are shown at midmonth