Early this year, a surprise space rock made headlines around the globe when the International Asteroid Warning Network sounded its highest alarm since its creation in 2013. Threat levels for the newly discovered asteroid, named 2024 YR4, were steadily increasing rather than waning, and experts estimated that the superyacht-sized rock had as much as a 1-in-33 chance of hitting Earth in just eight years. Its relatively long four-year orbit meant it would not be detectable again until 2028 on its final pass, leaving very little time for intervention.

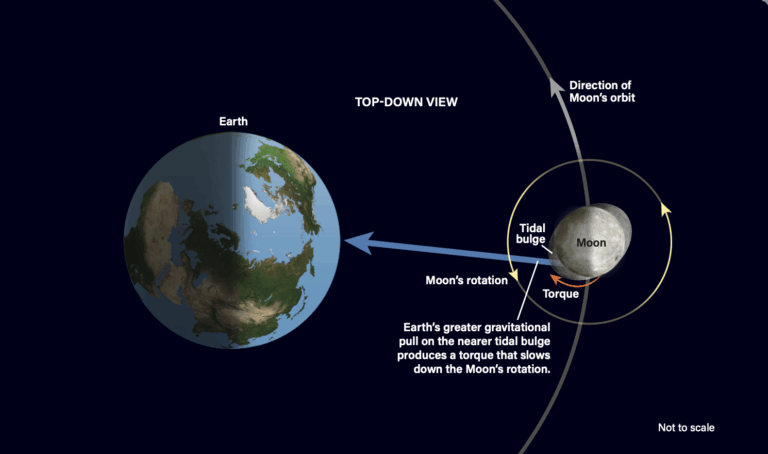

Scientists were concerned, but weeks of additional tracking granted a reprieve. Further data indicated that YR4 would miss Earth, though still have a 1-in-25 chance of hitting the Moon in 2032. Relieved for the moment, astronomers nonetheless caution that a major impact by a large near-Earth asteroid (NEA) is just a matter of time.

Asteroids have pummeled Earth for eons — some with planet-changing consequences — but for the first time in human history, we have the technology to spot these threats before they arrive. A network of telescopes and their operators scan the skies as part of humanity’s early warning system against hazardous asteroids, an effort known collectively as planetary defense. Their goal is to catalog and track every solar system rock headed our way that’s large enough to flatten a city — not to mention end civilization as we know it.

Over the past few decades, astronomers have made slow but steady progress toward this goal with dedicated NEA surveys. New cutting-edge observatories like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which began operations earlier this year, are turbocharging these efforts, finally bringing it within reach.

Asteroid hunters

The modern era of planetary defense — a term coined by U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Lindley Johnson three decades ago — had its genesis after humanity had a ringside seat to a spectacular demonstration of cosmic violence. Discovered by legendary asteroid- and comet-hunting husband and wife Eugene and Carolyn Shoemaker, together with David Levy, Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 barreled into Jupiter in 1994. A few fragments left atmospheric scars larger than Earth and packed punches 600 times more powerful than our planet’s entire nuclear arsenal.

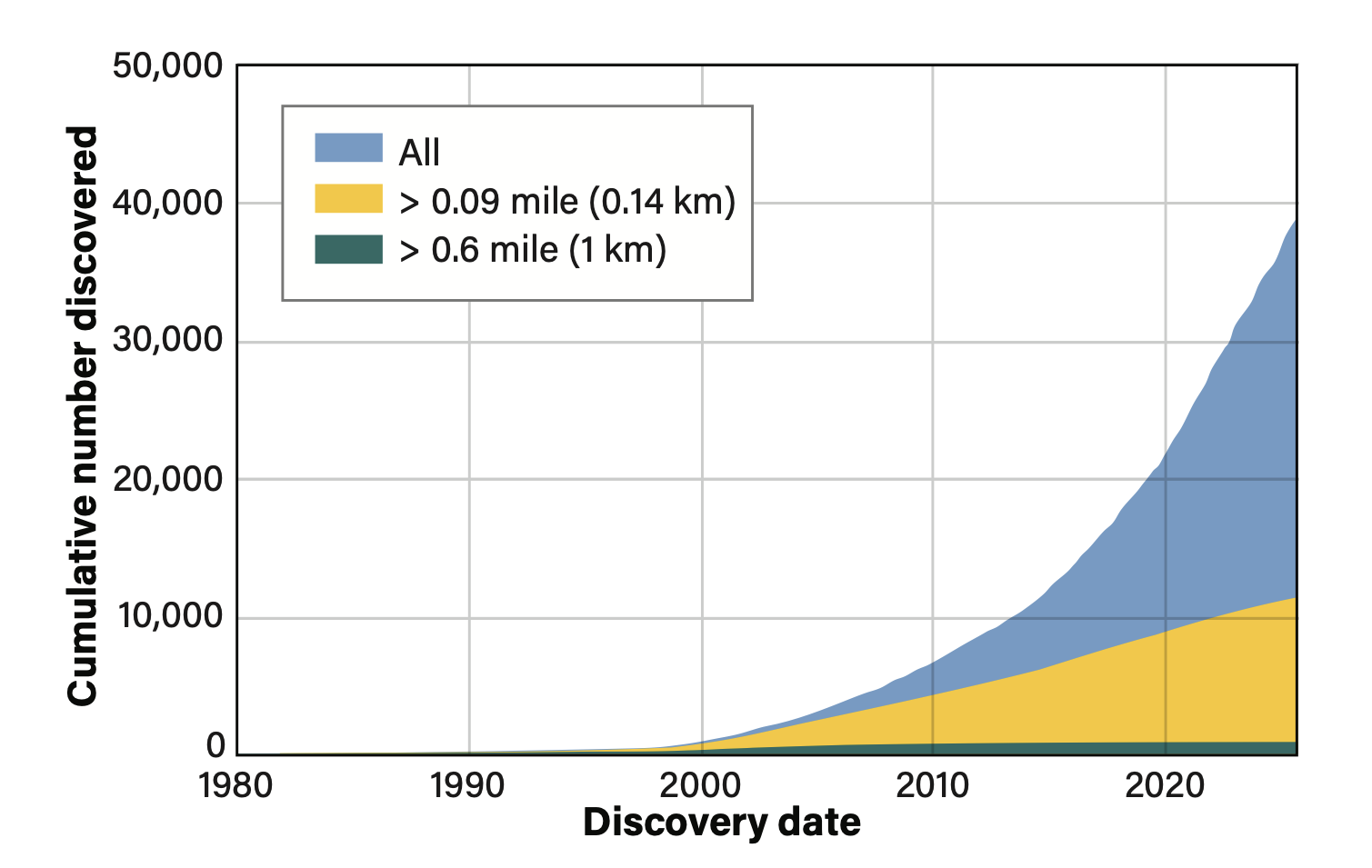

The event was a wake-up call for Congress and NASA, prompting the development of a comprehensive asteroid-search program under the auspices of what is now called the Planetary Defense Coordination Office. In 1998, Congress formalized this effort by ordering NASA to launch an all-out search for asteroids larger than 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) — the size threshold for global catastrophe. About 200 were known at the time, or some 20 percent of that total population, according to Paul Chodas, director of the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California.

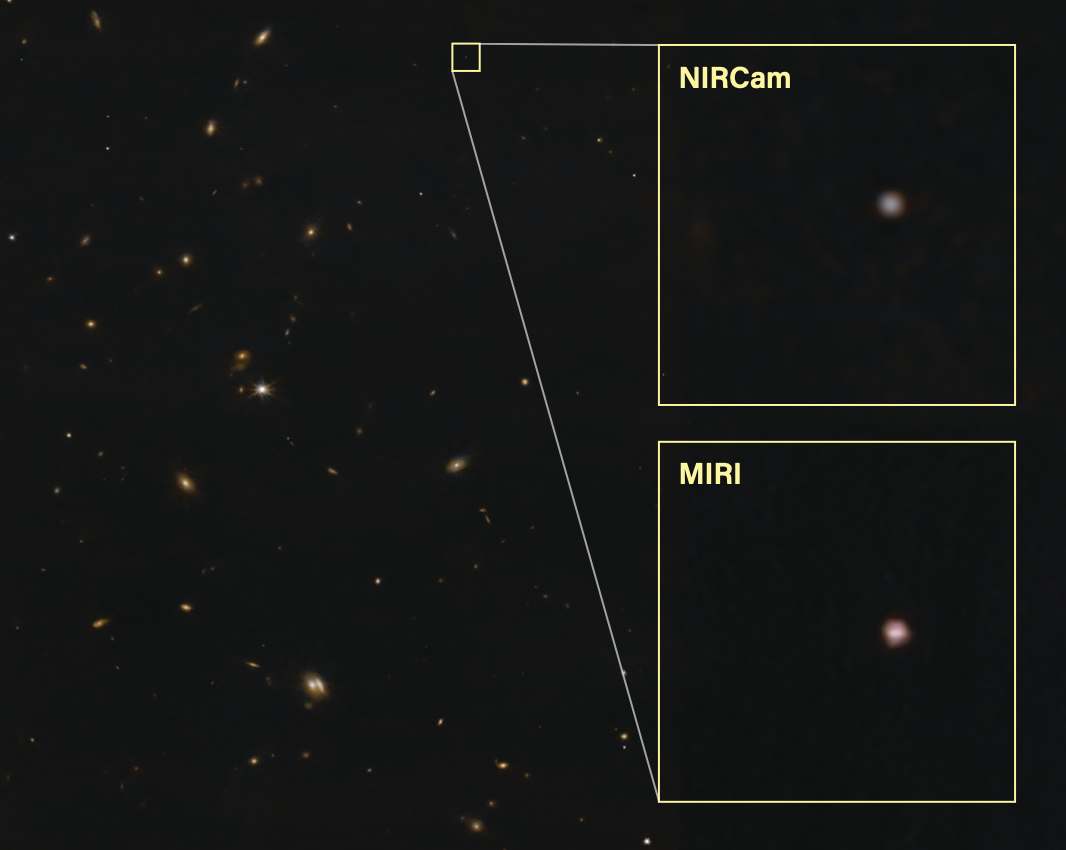

Since then, technology and tools have steadily improved, from film to digital detectors and from a handful of telescopes to an international network. Three full-time surveys — the Catalina Sky Survey (CSS) in Arizona; the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS) in Hawaii; and the robotic Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) in Hawaii, Chile, and South Africa — now scour the skies year-round. They will soon be joined by the vast surveying capacity of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, and in 2027 by the space-based infrared NEO Surveyor observatory. From space, NEO Surveyor will spot objects inside Earth’s orbit using mid-infrared detectors that don’t require an asteroid to reflect sunlight to make it detectable.

Eugene Shoemaker, who died in 1997, remains a touchstone of the community. “Gene gave me my mantra,” says Greg Leonard, telescope operator for the CSS. Leonard represents a generation of asteroid hunters directly inspired by Shoemaker’s work. As a young college graduate in 1992, he interned under Shoemaker, doing two-week stints at Mount Palomar searching for Earth-crossing asteroids and comets. He now spends most nights atop Mount Bigelow, northeast of Tucson, Arizona, searching for moving dots against thousands of stationary stars on a computer screen. “Gene told me that something is discovered for the first time only once, so put yourself in a position to discover,” he says.

That is just what Leonard did when he joined the CSS 10 years ago with a background in geology and a love for astronomy. He discovered his own comet in 2021, C/2021 A1 (Leonard), which became known as the Christmas Comet and was featured in media worldwide.

Leonard and seven other full-time CSS observers use several telescopes outside Tucson — two full-time for searching and up to three for follow-up confirmations. The 27-inch Schmidt telescope Leonard operates can spot NEAs as small as a person 2 million miles (3.2 million km) distant — “a testament to the exquisite sensitivity of our CCD,” the postcard-size digital sensor in the instrument.

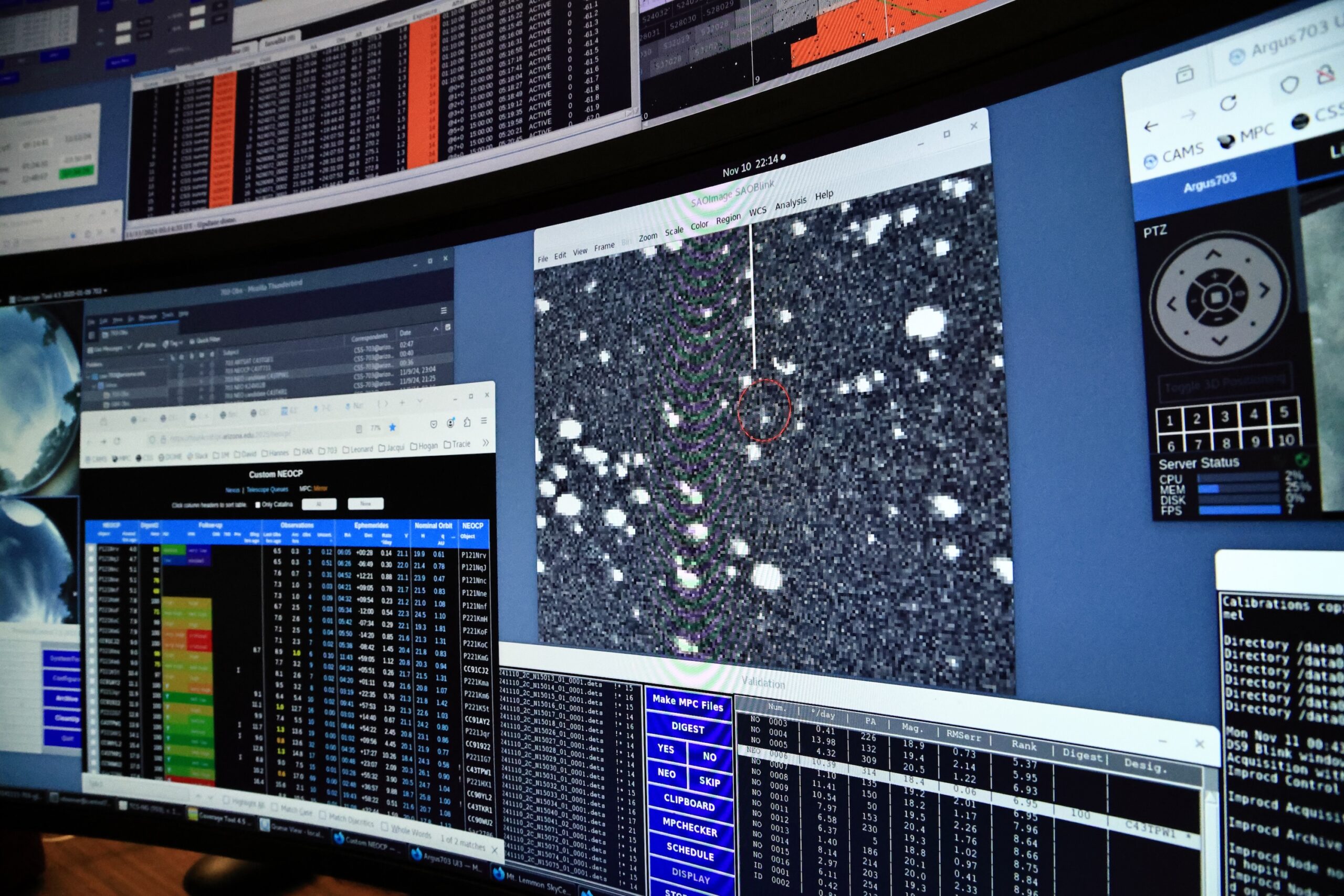

“I spotted three candidates just last night [Nov. 9, 2024],” Leonard says, pointing to a sweep of monitors in the cramped control room. One screen displays a colorful chart that tracks the motions of the telescope whirring above us — 14-second exposures, repeated four times each, covering hundreds of fields, or roughly half the sky, per night. Imagery is constantly processed while the telescope slews — it takes 10 minutes from exposure to completion. Another telescope 4 miles (6.4 km) away atop Mount Lemmon specializes in dimmer objects — down to magnitude 22, a million times fainter than our eyes can see — and takes two weeks to cover half the sky.

Detection software and machine learning aid in the search, but there is still an important human factor. Leonard pulls up an image from the previous night, featuring a riot of stars on a black field with a red circle pinpointing his discovery. A set of four photographs shows it changing position against a static field of stars — movement that Leonard noticed as he reviewed the images.

“Humans are integral to the Catalina Sky Survey,” says CSS director Carson Fuls. “We manually review possible candidates because humans are highly adapted to detect slight motion.”

By animating successive photos, observers can spot movement even when an object is very faint. If software and human agree on a find, detections are immediately submitted to the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics’ Minor Planet Center (MPC) and posted worldwide to allow other observatories to double-check the sightings. The rapid pace is vital: The optical visibility of an asteroid depends not only on its position but also those of Earth and the Sun, and that geometry can change quickly. “What matters with discovery of near-Earth objects is how fast you can report it so someone else can follow up to do targeted observations, because otherwise, it’s gone,” says Fuls.

Once the MPC confirms a detection (provided it isn’t dismissed it as an artifact, space junk, or a previously known near-Earth object [NEO]) it names them — all within 24 hours.

According to Fuls, the CSS vets the 20 most likely asteroid candidates in each of the hundreds of fields per night. “Reviews of aggregate historical data show that 98 percent of detected NEOs are ranked in [these] top 20 potential detections,” says Fuls. “But that leaves dozens in each field we don’t have time for.”

To address that gap, the CSS posts nightly imagery for the next 20 most likely candidates for the public to review on the Zooniverse citizen science platform as part of The Daily Minor Planet project. More than 7,000 citizen scientists have logged on to try their hand at asteroid hunting since the project’s inception in October 2023, spotting some 3,500 previously undetected asteroids and discovering three new NEOs.

Fuls says that the introduction of the Rubin Observatory will help discover even more NEOs. And Mario Juric, head of Rubin’s LSST Solar System Pipeline Group, adds, “As we [Rubin] come online, my bet is the entire planetary defense discovery system will be reoptimized to draw on specific strengths of each program and the whole will be much more powerful than any individual piece.”

Rating risk

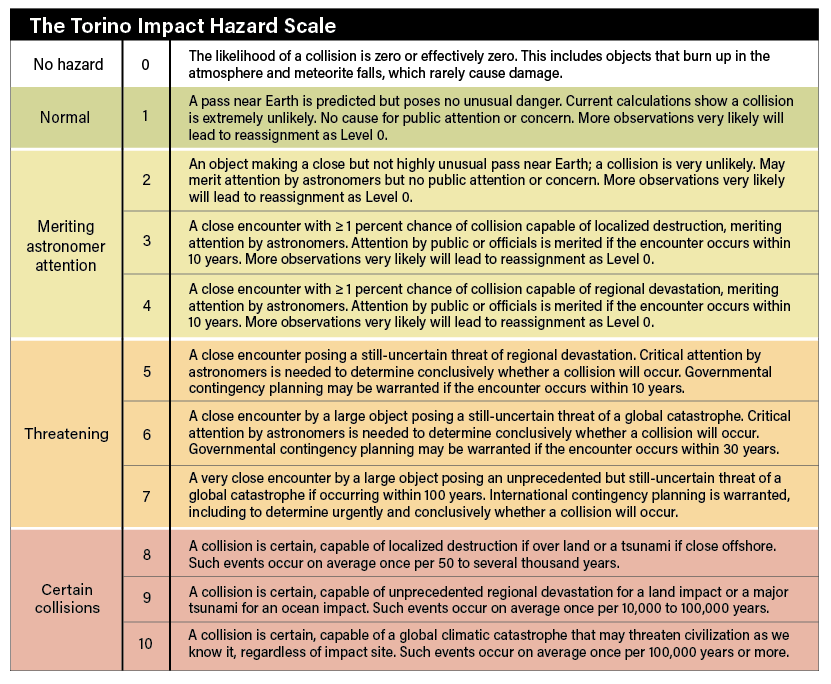

Astronomers rate asteroid risk on the 10-point Torino Impact Hazard Scale, which uses colored tiers. White (0) and green (1) indicate effectively no chance of collision or a chance so small that it is of no concern. Yellow (2–4) designates asteroids with more than a 1 percent chance of collision, capable of inflicting localized destruction and warranting attention if the encounter will occur within a decade. Orange (5–7) identifies objects that pose a serious threat of regional destruction, with different levels warranting attention depending on the timing of the encounter (ranging from 10 to 100 years). Red (8–10) encompasses all definite collisions capable of causing destruction within any amount of time. Level 10, the highest rank on the scale, is reserved for extinction-level threats

Despite all the headlines, YR4 at its worst rated a mere 3 on the Torino Scale. It is now 0.

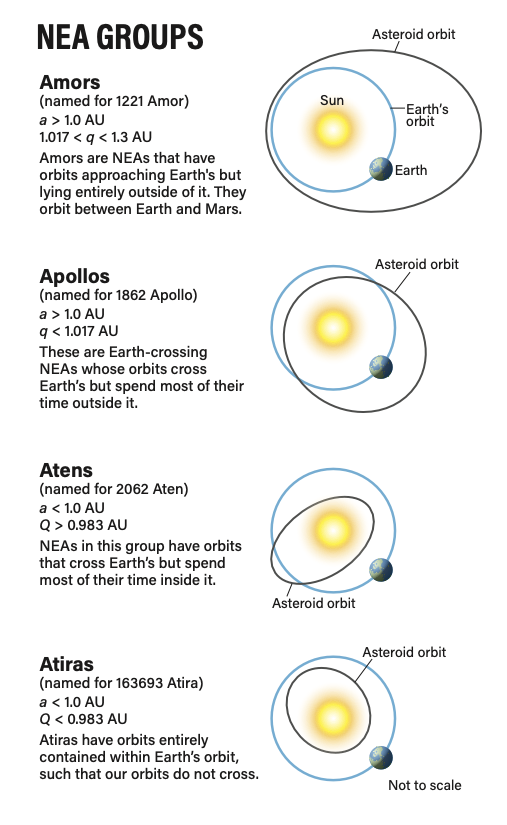

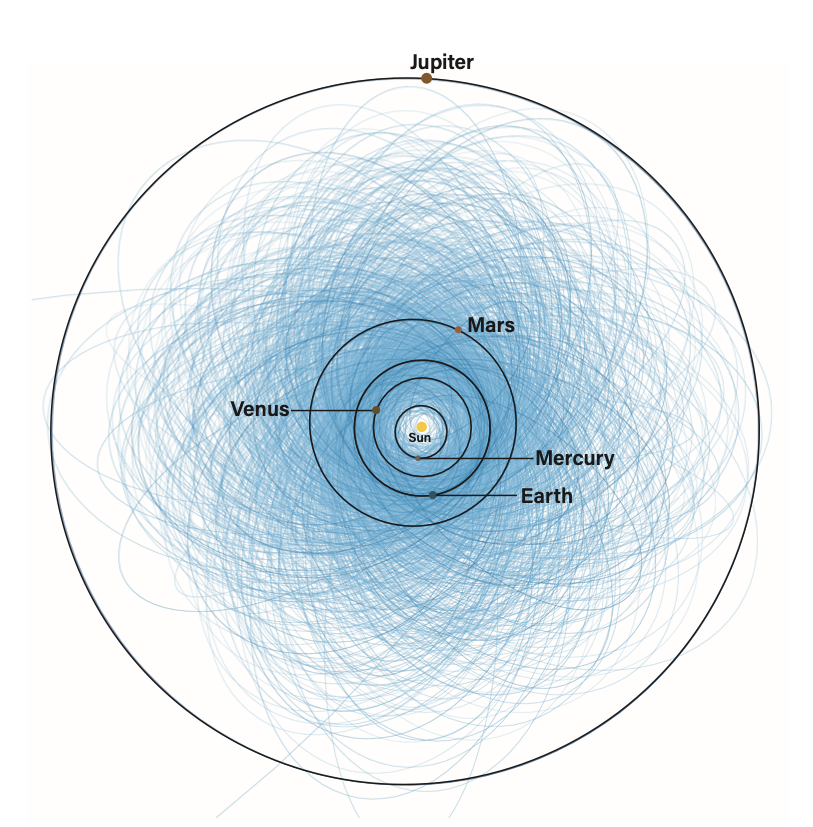

Near-Earth asteroids

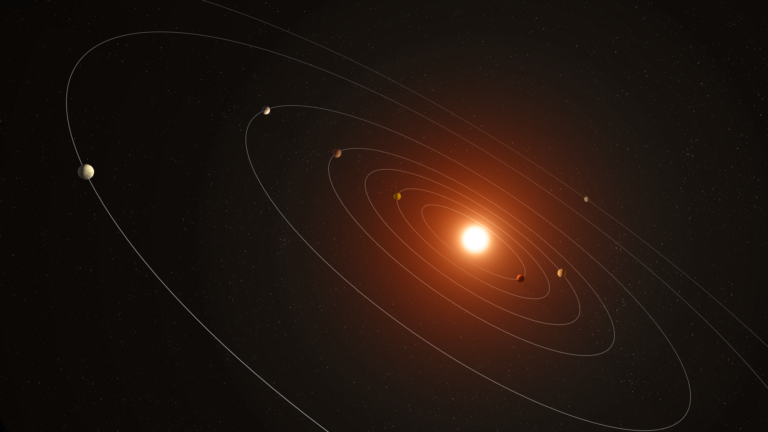

NEOs, which include NEAs, are asteroids or comets that orbit the Sun with a perihelion, or closest point to the Sun, of 1.3 astronomical units or less. (One astronomical unit, or AU, is the average Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles [150 million km].) If an asteroid exceeds 460 feet (0.09 mile; 140 m) in width and comes within about 4.6 million miles (7.5 million km; 0.05 AU) of Earth’s orbital path, it is designated a potentially hazardous asteroid (PHA), capable of widespread destruction.

In seeking to fulfill Congress’ mandate to search for asteroids larger than 0.6 mile (3,168 feet; 1 km), CSS and other surveys face a daunting task. “There’s on the order of 24,000 NEAs that are 140 meters [460 feet] and larger, depending on how you count them,” says Chodas. “We’ve found 9,600 NEAs and about 900 that are larger than 1 kilometer [0.6 mile], but by that measure, we’re not even halfway,” he says.

That’s because determining how many total NEAs exist is tricky. “The percentage of NEAs that have been discovered so far depends tremendously on size,” Chodas explains. “I give the example of a bunch of fish in a small lake. The fish are like asteroids. When you go fishing, you tag them as you catch them [and] throw them back in. You do this day after day, and after a month or two, when 90 percent of the fish you’re catching are tagged, you know you’ve found 90 percent of the population. But the smaller the size limit you’re interested in, the larger the population, and the smaller the completion ratio.”

In 2005, NASA was directed by Congress to more specifically identify 90 percent of NEOs larger than 460 feet (140 m); Chodas says some 45 percent of the expected population has been identified. But “the population number rises exponentially as [you] go to smaller threshold sizes: The population is roughly 100,000 at the size of 2024 YR4 (which was about 60 m [197 feet] in size), and if we go all the way down to a few meters in size, the population of NEAs is over a billion.”

Crash avoidance

For Chodas, the real challenge is determining trajectories, not numbers. He has been predicting the motions of asteroids and comets with pinpoint accuracy for decades. Chodas is also tasked with inventing the fictional asteroids for Planetary Defense Conferences — a biennial forum for thwarting hypothetical killer space rocks, akin to war games for astronomers and engineers.

CNEOS determines impact threat for all reported NEOs — even candidates that have not yet been confirmed. Objects in the MPC’s database of candidates are evaluated by CNEOS’ Scout software, which performs preliminary trajectory and threat analysis to identify short-term, imminent impactors. The MPC also operates the Sentry system, which looks at the confirmed asteroid catalog to assess whether an impact is possible in the next 100 years. Both systems continually update risk assessments as additional data come in.

For several weeks after YR4 was discovered by ATLAS in Chile around Christmas 2024, the risk of impact kept rising with more data rather than diminishing, triggering alarm. Coincidentally, the hypothetical asteroid for this year’s Planetary Defense Conference in May was eerily similar to YR4 in projected size and impact probability, even though it was invented months before YR4’s discovery. The uncanny similarity underlined how vital such “war games” can be, a reminder to scientists that inevitably their efforts will not be a mere drill.

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test

Until recently, humans were no better prepared to ward off killer asteroids than the dinosaurs. That changed in September 2022, when NASA’s roughly half-ton Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft smashed into the 525-foot (160 m), 5.5-million-ton asteroid Dimorphos at nearly 14,000 mph (22,500 km/h), generating the energy of three tons of TNT.

Dimorphos orbits an asteroid five times its size, called Didymos. Astronomers used this to track the result of the impact by watching the pair’s orbital period shrink after the nudge. The impact ultimately shortened the system’s orbital tango by 32 minutes.

Compared to the tens of miles per second at which Dimorphos whips around the Sun, this is a tiny fraction of its momentum — tenths of an inch per second. According to David Jewitt, an astronomer at the University of California, Los Angeles, who published a study about DART’s aftermath in July 2023, any useful deflection of a larger asteroid would require a far greater shove or need to occur decades ahead of an impending collision to have a cumulative effect. “If you wanted to deflect a bigger asteroid — for example, something 10 times larger — you’d need 1,000 DARTs to get the same minuscule deflection,” he says.

A larger impact, however, means more debris. And in the case of an asteroid headed for Earth, that debris could spell trouble, raining down on the planet even if the larger impactor doesn’t. Months after the collision, Jewitt and colleagues discovered a swarm of boulders from Dimorphos in Hubble imagery, some as large as houses, drifting away in all directions. They are now waiting for ESA’s Hera spacecraft to rendezvous with Didymos in late 2026 to find out the fate of this debris

Cosmic shooting gallery

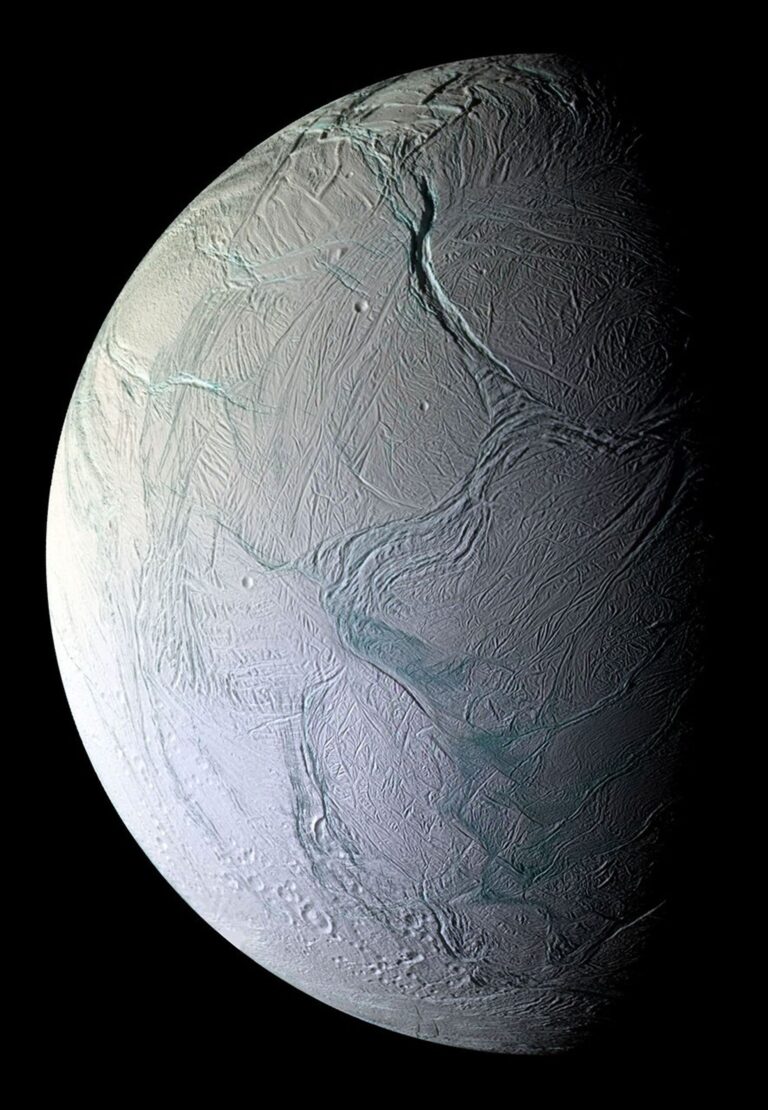

Earth was once a frequent victim of NEOs, though our scars are hidden by eons of erosion, uplift, and sedimentation. Today, the number of potential impactors in our vicinity is far fewer than in the solar system’s youth. But a single strike like the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor over Russia — an unexpected 10,000-ton asteroid that snuck in from behind the Sun and exploded high in the stratosphere with 30 times the energy of a small atomic bomb — reminds us that we are still whirling through a cosmic shooting gallery.

We are becoming better prepared. “We’ve predicted impacts to within a few seconds and within a kilometer with just a few hours’ warning,” says Chodas, referring to hits in Sudan in 2008 and western Europe in 2023 and 2024. “We got out the predictions, and people actually filmed fireballs coming through the atmosphere.”

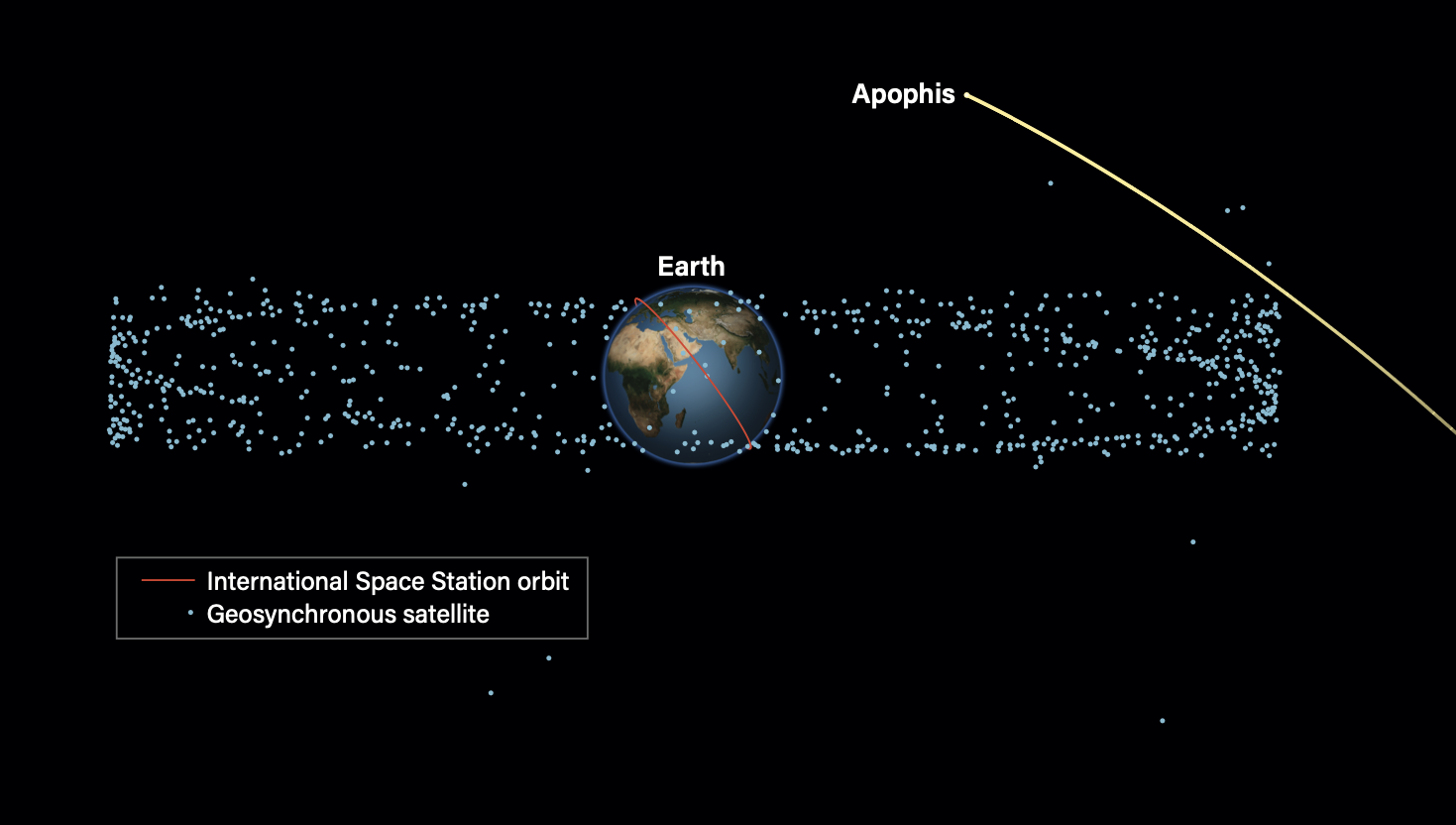

Still, a spectacular reminder of our vulnerability is just around the corner. In April 2029, Earth will experience a remarkably intimate visit from an asteroid the size of an aircraft carrier passing much closer than the Moon. It will be a once-in-a-millennium occurrence: an asteroid visible with the naked eye, sure to create sensational headlines.

Discovered in 2004, 99942 Apophis (named after the monstrous Egyptian serpent god intent on disrupting the cycle of night and day) will pass within 20,000 miles (32,000 km) of Earth, closer than many satellites in geosynchronous orbit. Based on extensive observations and calculations, experts like Chodas have determined that it will harmlessly glide by and not pose a threat for at least 100 years.

Space agencies are excitedly preparing for this exceptional encounter with a PHA. NASA has reconfigured its Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security — Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) mission, which previously returned samples from asteroid 101955 Bennu, as the OSIRIS-APophis EXplorer (OSIRIS-APEX) with a new goal: to rendezvous with Apophis. With fuel already low, it can only fly by Apophis. The European Space Agency, on the other hand, hopes to redirect Hera after its visit to the asteroid Didymos to study the aftereffects of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART). Under the new name the Rapid Apophis Mission for Space Safety (Ramses), it will rendezvous with Apophis before the asteroid flies by Earth and remain with it throughout its pass.

Both missions will offer deep insights into how Earth’s tidal forces interact with incoming space rocks. Combined with new surveys like Rubin’s and dedicated observers like Leonard and Chodas, scientists are getting ever closer to the ability to plan for the next uninvited guest to crash the party, and to hopefully thwart its mission of chaos and doom.