On Jan. 15, 2025, the Gaia spacecraft took its last image. Then the craft ran a final round of engineering tests, fired its thrusters to leave Earth behind, and slipped into an orbit around the Sun, finally turning off on March 27.

After more than a decade in operation, 3 trillion observations, and 2 billion stars observed, Gaia has earned its retirement. Launched by the European Space Agency (ESA) in 2013, Gaia’s goal was “to map a billion stars,” and it succeeded.

Compiling the map of where these stars are and how they move paints a picture of our entire galaxy — even the dark matter, whose gravitational influence subtly tugs on the stars. Along the way, Gaia found brown dwarfs, exoplanets, and quasars. Peering down to 20th magnitude, Gaia also spied stars in the Milky Way’s satellite galaxies, the small stellar cities that orbit just outside our own, to reveal how they interact with our galaxy now and in the distant past.

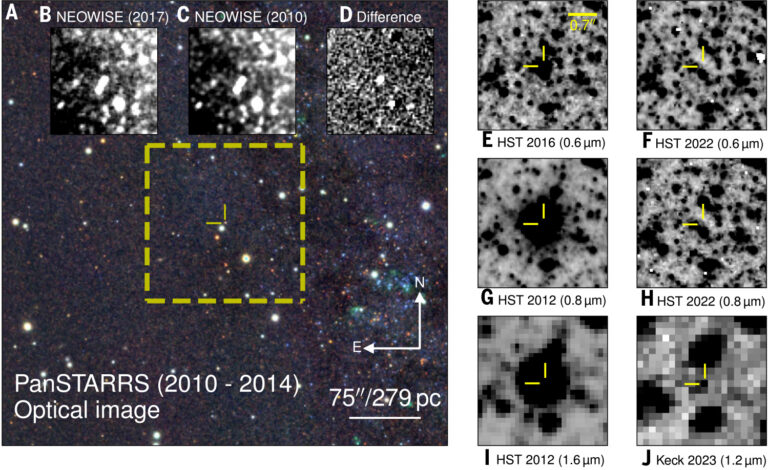

Though Gaia’s observations are complete, scientists are still analyzing the hundreds of terabytes of information sent from space. And the Gaia data are being released to the public in stages, as is common for most large, long-lasting surveys. But the data are already proving wildly useful, informing the science of exoplanets, black holes, and more. The survey has thus far uncovered new information about ancient collisions that sculpted the Milky Way, honed our picture of its current shape, discovered an exoplanet, and potentially revealed the central black hole in a neighboring galaxy. And that’s with just the first three years of data. More discoveries are sure to come.

The Gaia mission will return new discoveries for years, most likely decades to come. But its accomplishments thus far have already blown open our understanding of the Milky Way, both past and present.

An impressive assignment

The Gaia spacecraft was responsible for obtaining the most precise measurements ever of more than a billion stars’ positions, distances, and motions. This catalog was meant to stand on the shoulders of Hipparcos, a spacecraft launched in 1989 with a similar mission. That satellite produced high-precision data for some 118,000 stars and lower-precision data for 2.5 million stars. Gaia outstripped its predecessor by a factor of a thousand, while taking measurements 200 times more precise.

Gaia was conceived as part of ESA’s Horizon 2000+ campaign, a long-term development guide similar to the Decadal Survey used by American space research agencies. First proposed in 1993, Gaia was officially confirmed in 2000. Constructed by several European partners, the Gaia spacecraft was completed in June 2013. Originally scheduled for a November launch that year, the mission was briefly delayed when ESA officials decided to replace two transponders, which had proved faulty in a different spacecraft already in orbit.

Gaia ultimately launched smoothly from Korou, French Guinea, aboard a Soyuz rocket and Fregat upper stage on Dec. 19, 2013. The craft spent four days in a temporary orbit near Earth to deploy its sunshield and undergo tests before launching on a 30-day cruise out to the 930,000-mile (1.5 million kilometers) distant Earth-Sun Lagrange 2 point (L2), a common orbital destination for telescopes requiring exceptionally cold and dark views of space. Gaia would then spend its lifetime on a 180-day orbit around this spot. The telescope saw first light a week before reaching its final destination, imaging roughly 18,000 stars over the course of three hours on Jan. 8, 2014, and even measuring its first parallax, of the star Sadalmelik (Alpha [α] Aquarii).

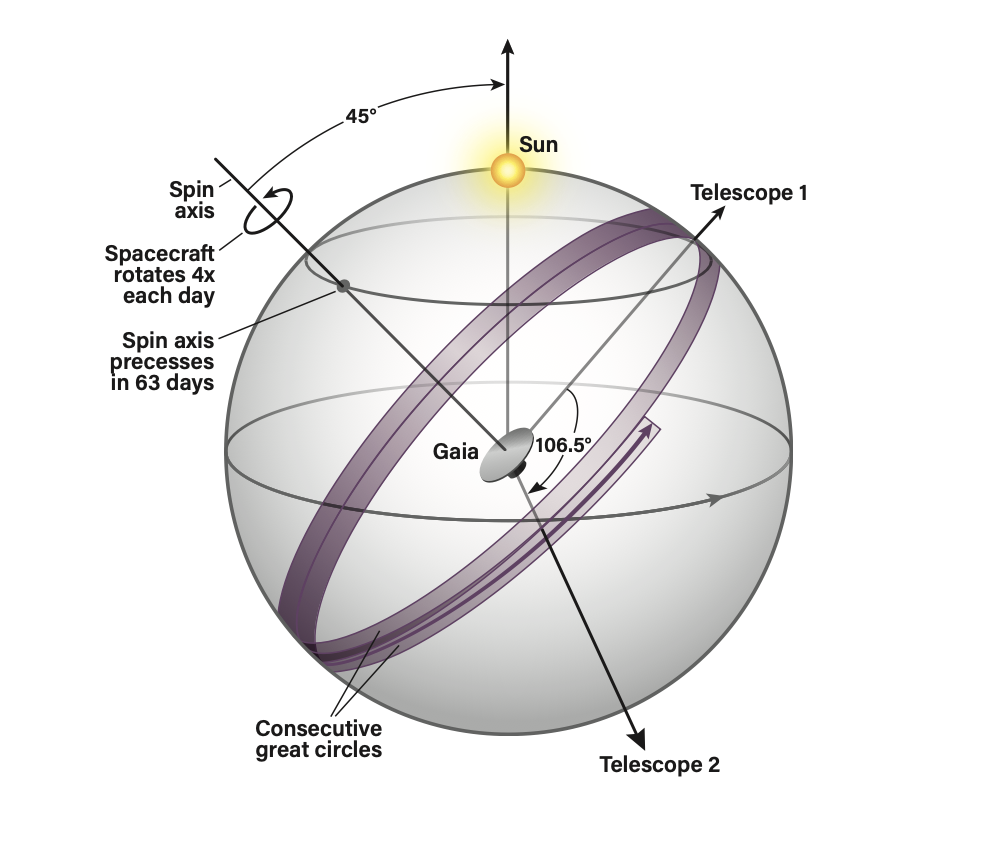

Gaia carried two twin telescopes, each with a primary mirror about 7.5 square feet (0.7 square meter); for comparison, the James Webb Space Telescope’s mirror covers some 270 square feet (25 m2). But Gaia had a total of 10 mirrors, which reflected light back and forth on a path 115 feet (35 m) long in order to focus the light on its sensitive detectors, feeding into three instruments. An astrometric instrument measured the position and movements of stars on the two-dimensional sky (which, over time, allowed astronomers to derive a star’s distance). A photometric instrument recorded their colors (which tell us a star’s temperature, mass, and composition). And a spectroscopic instrument measured the Doppler shift of stars, recording their radial motions toward and away from Earth.

The astrometric instrument was Gaia’s bread and butter. Like Hipparcos before it, Gaia’s two telescopes peered at two fields of view simultaneously, building up a catalog of the relative separation of stars on the sky to allow unprecedented precision in their positions. The two telescopes always pointed 106.5° apart as the craft rotated in a circle every six hours, one telescope trailing the other. The spacecraft was also inclined 45° from the Sun, precessing around that axis every 63 days. The combination of movements allowed Gaia to view each of its 2 billion targets, scattered across the whole sky, roughly 14 times a year.

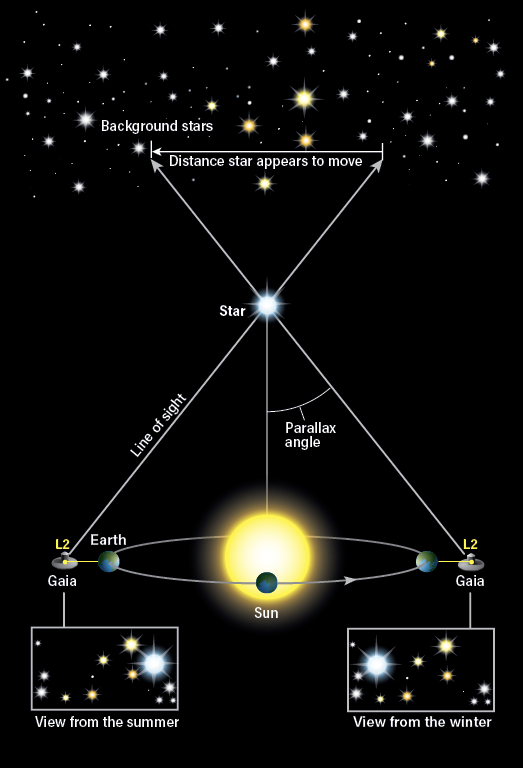

An often surprising aspect of astronomy is that it is extraordinarily difficult to measure the distance of objects in space. In fact, there’s only one direct method, called parallax, which measures the apparent change in position of a nearby object compared to one that is more distant, which appears fixed. (See “Measuring parallax” below for more details on how parallax works.) Gaia obtained parallax measurements of a billion objects, some 99 percent of which had never been accurately measured before.

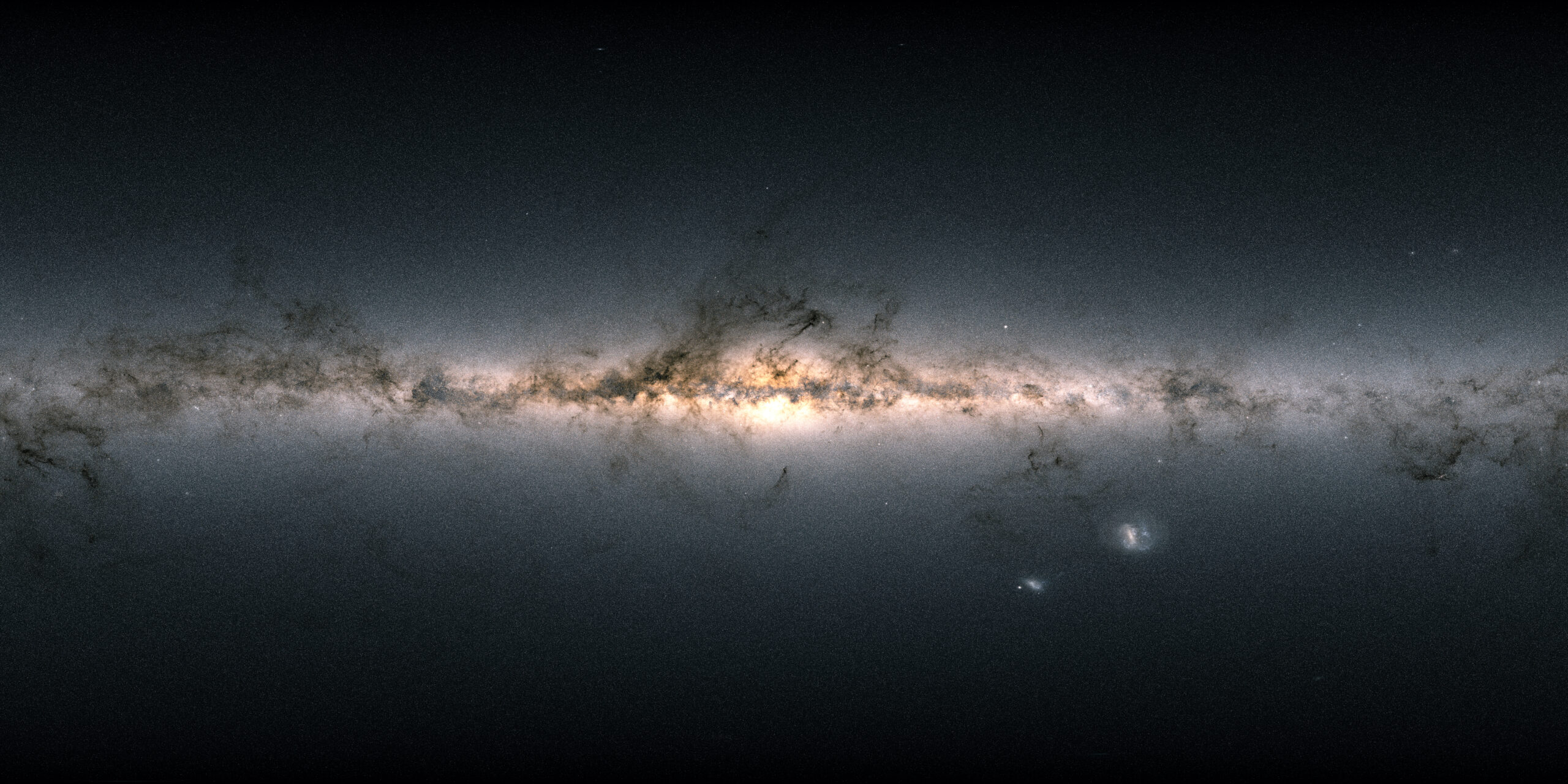

A huge amount of Gaia’s mission was aimed toward a better understanding of our home galaxy, the Milky Way. It’s a bizarre twist that while astronomers can observe thousands of nearby galaxies, mapping their stars, dust lanes, ripples, and bulges, producing breathtaking images along the way, we can’t take a simple picture of our own galaxy. But by obtaining precise distance and position measurements of billions of objects, Gaia can assemble a clearer map than ever before, building up the picture from the inside.

And of course, any survey as large as Gaia will turn up unexpected results, often the most delicious kind in science.

Measuring parallax

From its position at Earth’s L2 point, Gaia circled the Sun once a year along with our planet. As it did so, its position changed by some 186 million miles (300 million km) over the course of a year. By observing the same stars while on opposite sides of the Sun, Gaia used a technique called parallax to determine their distance.

As an observer’s position changes, nearer objects appear to move with respect to more distant ones. In this case, nearer stars appear to move more on the sky than farther suns when viewed six months apart, from opposite sides of Earth’s orbit. The two different sightlines to the same star — one on either side of our orbit — create a triangle, and the parallax angle is defined as half the angle of that triangle’s apex. By measuring the parallax angle of a given star, astronomers can use trigonometry to work out its distance.

A parallax angle of exactly 1 arcsecond (1″) means a star is approximately 3.26 light-years away — a distance defined as a parsec (from the terms “parallax” and “arcsecond”). Gaia was capable of measuring changes in star positions down to 0.000001″ over the course of a year. — Alison Klesman

A picture of home

Of the 2 billion stars Gaia spied, the vast majority lay within the Milky Way. By measuring their positions and distances, astronomers can develop a more detailed and accurate map of our galaxy. And by charting stellar motions, astronomers can understand not just the big picture, but the smaller eddies, currents, and clusters of stars moving within the greater river of the Milky Way.

For instance, astronomers have known for years that the Milky Way’s spiral isn’t flat — it is warped, with a distinct kink. Gaia was able to not only better measure the shape of that warp, but also measure how it wobbles, or precesses, over time. Gaia data showed astronomers that the warp precesses relatively quickly, with a period of less than 700 million years. This suggests something dramatic like a collision with another galaxy caused it, as opposed to a bulge in our galaxy’s dark matter halo, for instance, which would create a warp that precesses more slowly. The most obvious culprit is the Sagittarius dwarf spheroidal galaxy, which has probably collided with the Milky Way several times in the past as they slowly merge into one.

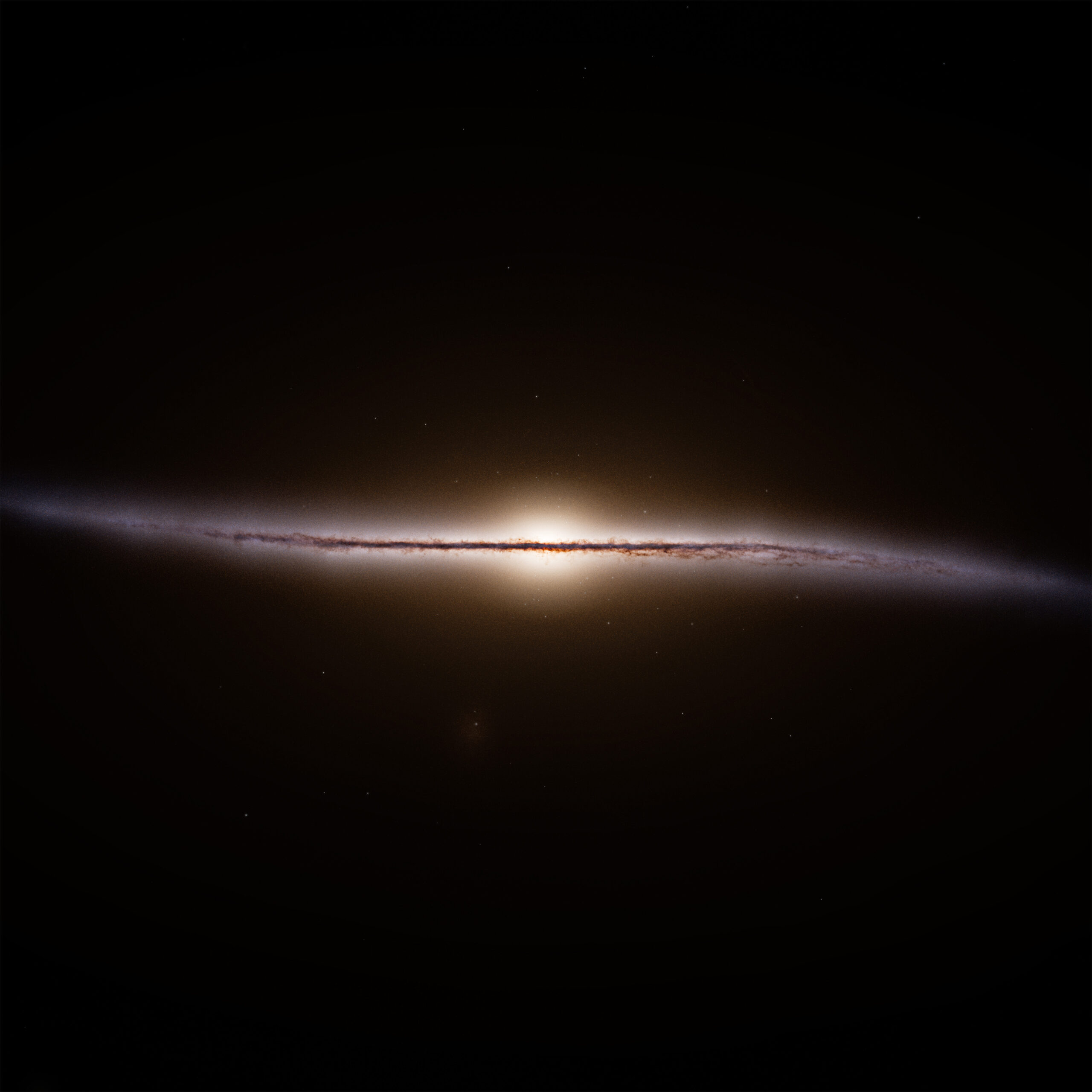

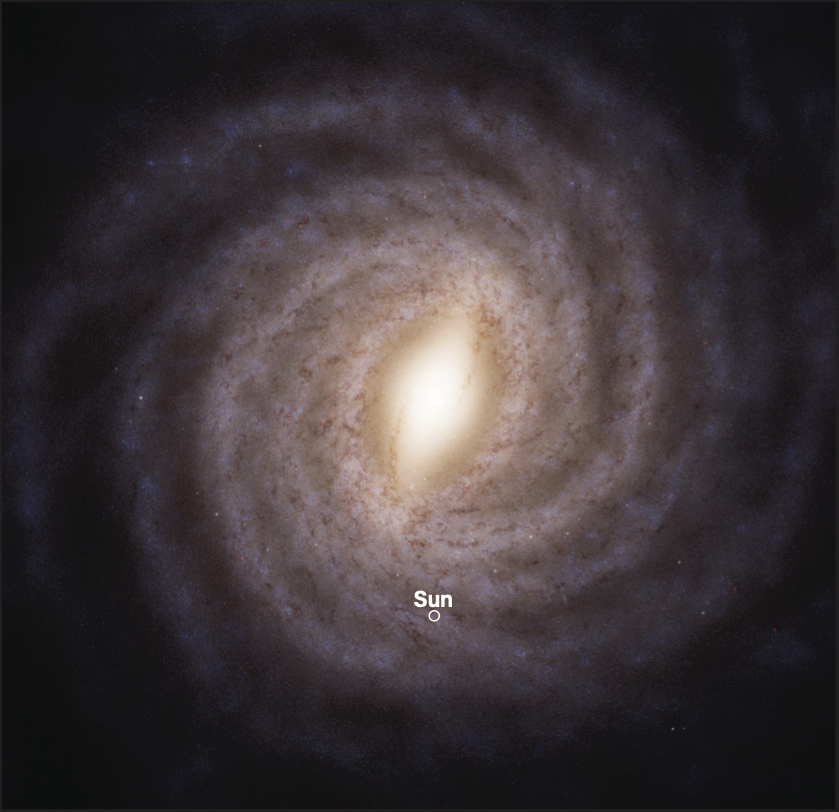

From our planet’s location inside the Milky Way, we cannot fly outside the galaxy to view what it looks like. By measuring the positions of billions of stars, however, Gaia has produced the most accurate maps of the Milky Way to date. These artist’s renderings show our galaxy from above (right) and the side (left), allowing astronomers to better understand its size, shape, and detailed structure. We now know the Milky Way is a barred spiral with multiple arms, and that its disk is not flat but warped, with one edge curving above the center and the other turned down below it.

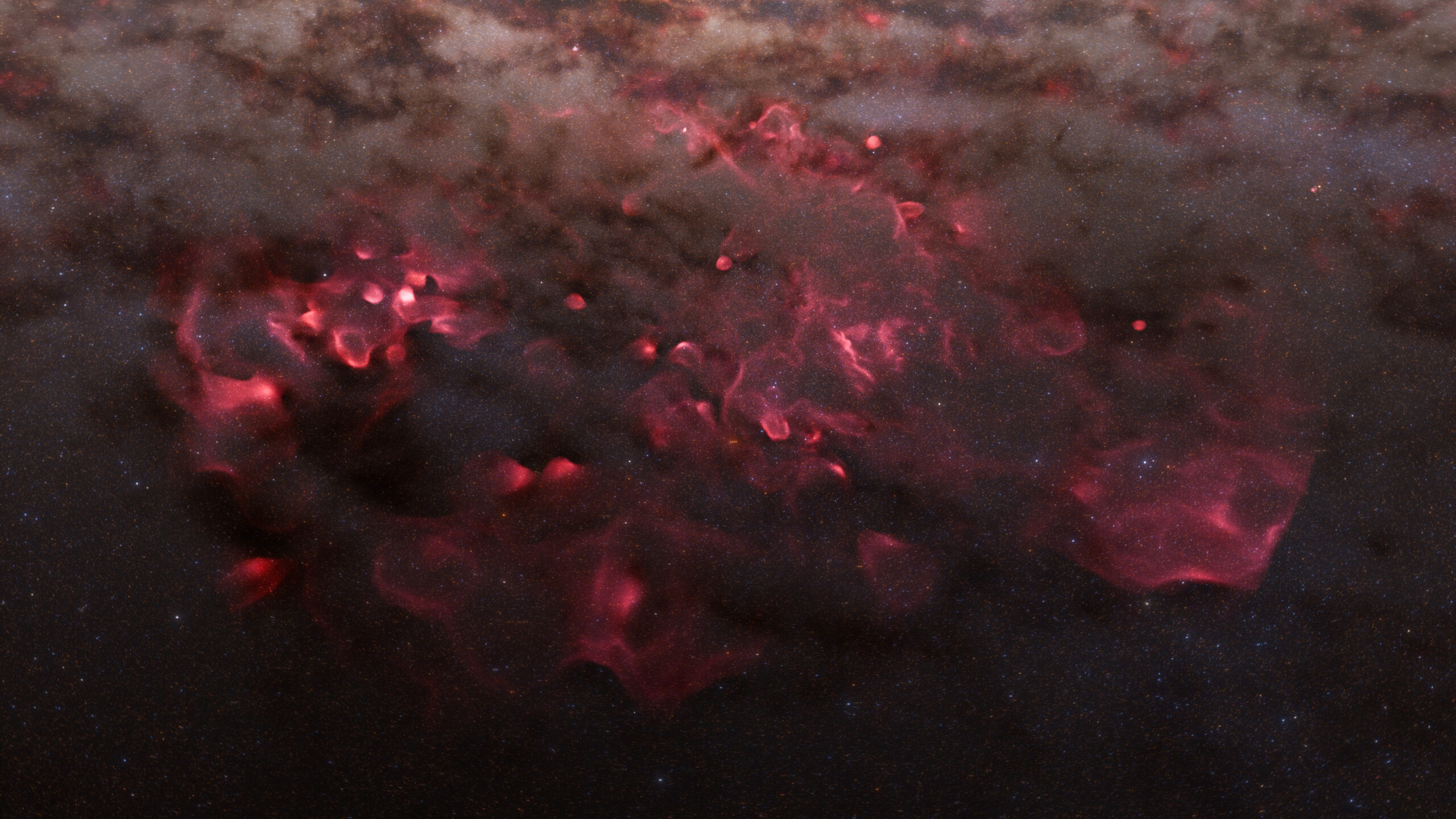

Closer to home, astronomers including João Alves at the University of Vienna in Austria have uncovered a 9,000-light-year-long ribbon of gas undulating like a wave in the plane of the galaxy, called the Radcliffe Wave. Part of the structure lies only 500 light-years from Earth, in our local spiral arm, and was previously known to researchers and called the Gould Belt. Dotted along its length are stellar nurseries, hotbeds of star formation. Parts of the massive cloud had been seen before, but only Gaia data revealed the structure as a whole, which now stands as the largest known gas structure in the entire galaxy.

“The Gaia data were absolutely crucial to our discovery,” Alves says. “This discovery significantly altered our understanding of the local Milky Way by replacing the idea of a Gould’s Belt with a much larger, wavelike structure that influences star formation across a vast region of the Milky Way, and that might have affected Earth’s climate about 14 million years ago” by introducing dust and radioactive particles into the solar system and Earth’s atmosphere as it passed through the cloud.

In the stars

Gaia data have also allowed astronomers to become stellar archaeologists. By tracking stars’ positions more precisely than ever before, astronomers can see how clusters of stars move together. This is a far more accurate way to discern clusters and groups of stars than by their positions, which can be misleading. After all, many stars that appear close together on the sky from Earth’s perspective are actually separated by many light-years, lying vastly different distances away from us. Astronomers try to counter this by finding stars that appear not only close to one another but also share characteristics, but this too is an inexact science, as the results can be skewed by dust and measurement uncertainties.

Not only can Gaia judge distance more accurately than most previous surveys, it also tracks motion, and stars that move together are much harder to misinterpret.

Stars are born together in groups, so by mapping stars in smaller clusters, groups, and associations, astronomers can paint a picture of when different patches of stars came to be. Their time of birth isn’t random, either. Many times, bursts of star formation are set off when galaxies collide or interact, mixing together dormant material.

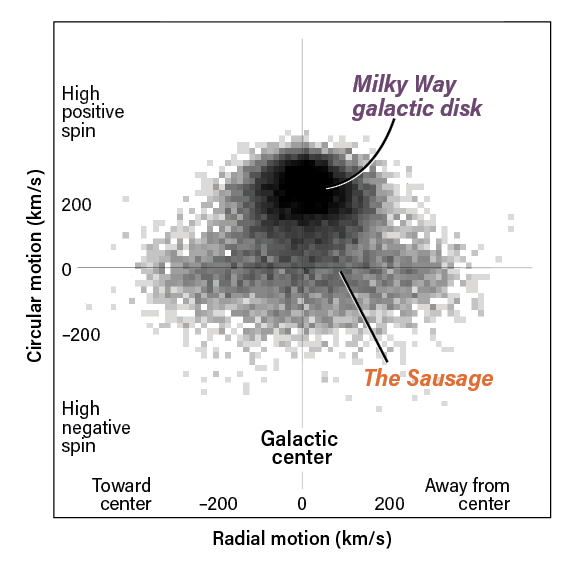

Perhaps most illuminating, Gaia identified a group of some 30,000 stars that move together in a pattern different from the rest of the Milky Way’s spiral flow, instead bobbing in and out of the center. Astronomers believe they are the remnant of a collision 10 billion years ago, when the young Milky Way and a galaxy now called Gaia Enceladus/Sausage merged. Another merger with a galaxy named Arjuna/Sequoia/I’itoi left behind globular clusters scattered through the Milky Way’s halo that all move retrograde, against our galaxy’s overall spin. Subsequent papers have uncovered even more mergers, painting a more complete history of our galaxy’s tumultuous evolution.

Astronomers have also been able to trace some of these mergers’ history from the location of specific clumps of stars. Among the discoveries are a series of ghostly filaments in the galaxy’s outer disk, which astronomers suspect are the bones of ancient spiral arms, excited by tidal interactions when other galaxies passed close by the Milky Way in its early days.

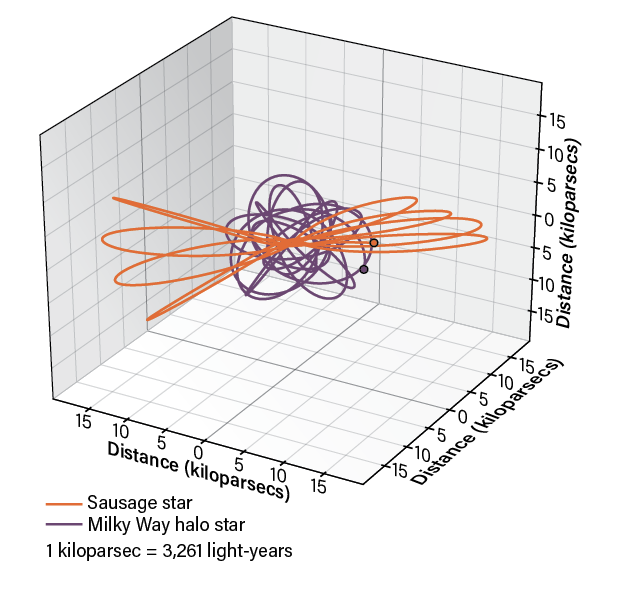

How the sausage was made

Looking at the way stars move allows astronomers to more easily see hidden groups of stars that are only revealed by their common motions through space. This is how researchers discovered the remnant of an ancient galactic collision. The plot at left includes the motions of 7 million stars measured by Gaia. On the vertical axis are stars’ circular motions (i.e., the way they orbit the center of the galaxy), while the horizontal axis shows their radial motion (i.e., motion only toward or away from us). Stars in the Milky Way’s disk have circular orbits with a speed of about 220 km/s (137 miles/second). But a separate set of stars (which appear to form a “sausagelike” shape on the plot, hence the Sausage moniker) have little of the expected circular motion around the galactic center, instead following very eccentric, needlelike orbits across the galaxy at some 400 km/s (250 miles/second). The plot at right shows the orbits of two different stars in 3D. Zero on each axis denotes the galactic center. The purple orbit follows a star in the galactic halo. The orange star is part of the Sausage group, with high radial motion toward and away from the galactic center, rather than the more circular motion of the halo star.

Beyond the Milky Way

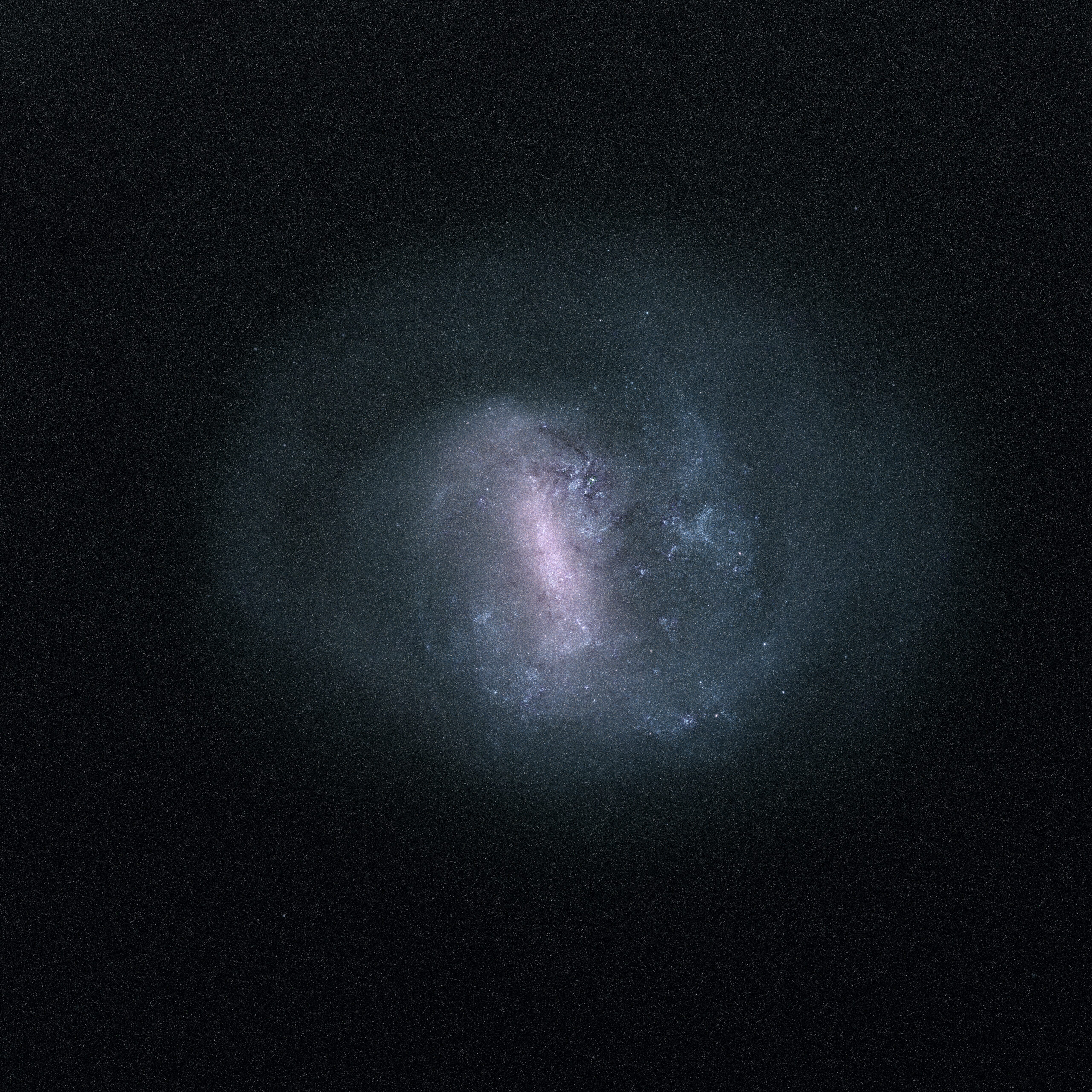

Gaia also spent time observing just outside the Milky Way, especially our close neighbor and familiar sight to observers in the Southern Hemisphere, the dwarf galaxy known as the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC). According to Gaia data, the LMC is some 10 percent more massive than astronomers previously thought.

Astronomers also looked at some 40 other dwarf galaxies orbiting just beyond the Milky Way, long assumed to be satellites. Physics tells astronomers that in an encounter between the Milky Way and a dwarf galaxy, the smaller object would be ripped apart and incorporated into the larger Milky Way in just one or two passes. (Galaxy “collisions” are usually repeat events, as the two objects crash through and bounce back before fully merging.) So, astronomers had presumed, if these galaxies are orbiting as intact structures, then they must be more massive than they appear. This had been taken as an indication that dwarf galaxies, too, must harbor dark matter reservoirs.

But Gaia data indicate that rather than following settled orbits, most of those galaxies are in fact encountering the Milky Way for the first time, based on their surprisingly high speeds. A true satellite would move more slowly as interactions between it and the Milky Way sapped its energy. These are newcomers, still full of vim, vigor, and velocity.

Because they’re not long-term satellites, however, they don’t need to contain the dark matter previously believed to be holding them together. So, now astronomers must rethink yet again assumptions of how dark matter accumulates and where in the universe this spectral material can be found.

Turning its eyes to a different kind of quick-moving target, Gaia observations of hypervelocity stars within the Milky Way (stars zipping around with high radial velocities compared to background stars) have brought further revelations about the LMC. Astronomers think such stars get their speed from some sort of “kick,” either from a companion star going supernova, or from veering too close to a black hole — particularly the Milky Way’s central supermassive black hole.

But when Jiwon Jesse Han of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics traced back the path of a certain subset of these stars, he found they originated in the LMC. And given the stars’ speed and history, the only plausible explanation for their particular distribution on the sky is that they were launched from the LMC by its own central supermassive black hole, making this dwarf just like its larger brethren galaxies. If confirmed, this would be a huge change in how we view our close neighbor, in which astronomers had previously found no solid evidence for a massive central black hole. That research was published in The Astrophysical Journal in March 2025.

And in February, the University of Amsterdam’s Guðmundur Stefánsson found an exoplanet in the Gaia data, dubbed Gaia-4 b, weighing in at nearly 12 times the mass of Jupiter. It is the first exoplanet to be discovered with Gaia data alone — while Gaia has detected other exoplanets in the past, they have either been confirmations of previously detected planets, or required supporting data. In the same paper, Stefánsson’s team also reports a brown dwarf, Gaia-5 b, about 21 times the mass of Jupiter.

All these results are just the beginning. Johannes Sahlmann, a Gaia project scientist, says, “New results … are pouring in at a very high rate of more than five peer-reviewed scientific publications per calendar day. Those results cover virtually any field of astrophysical research, often with transformative impact.”

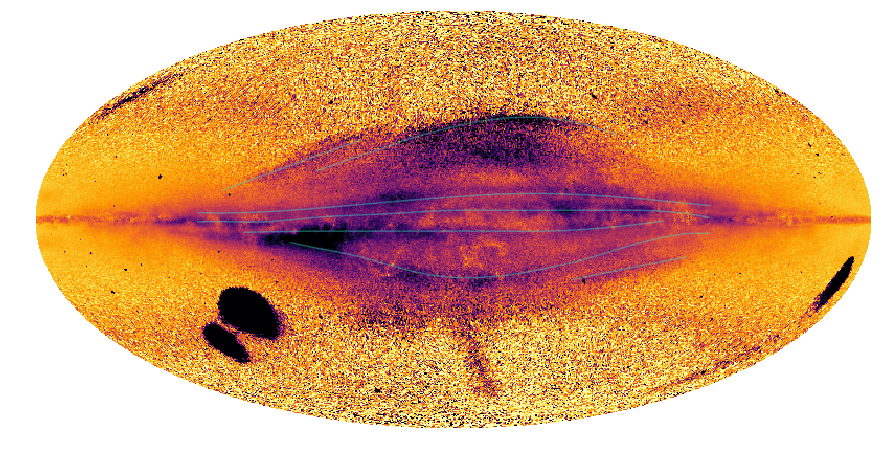

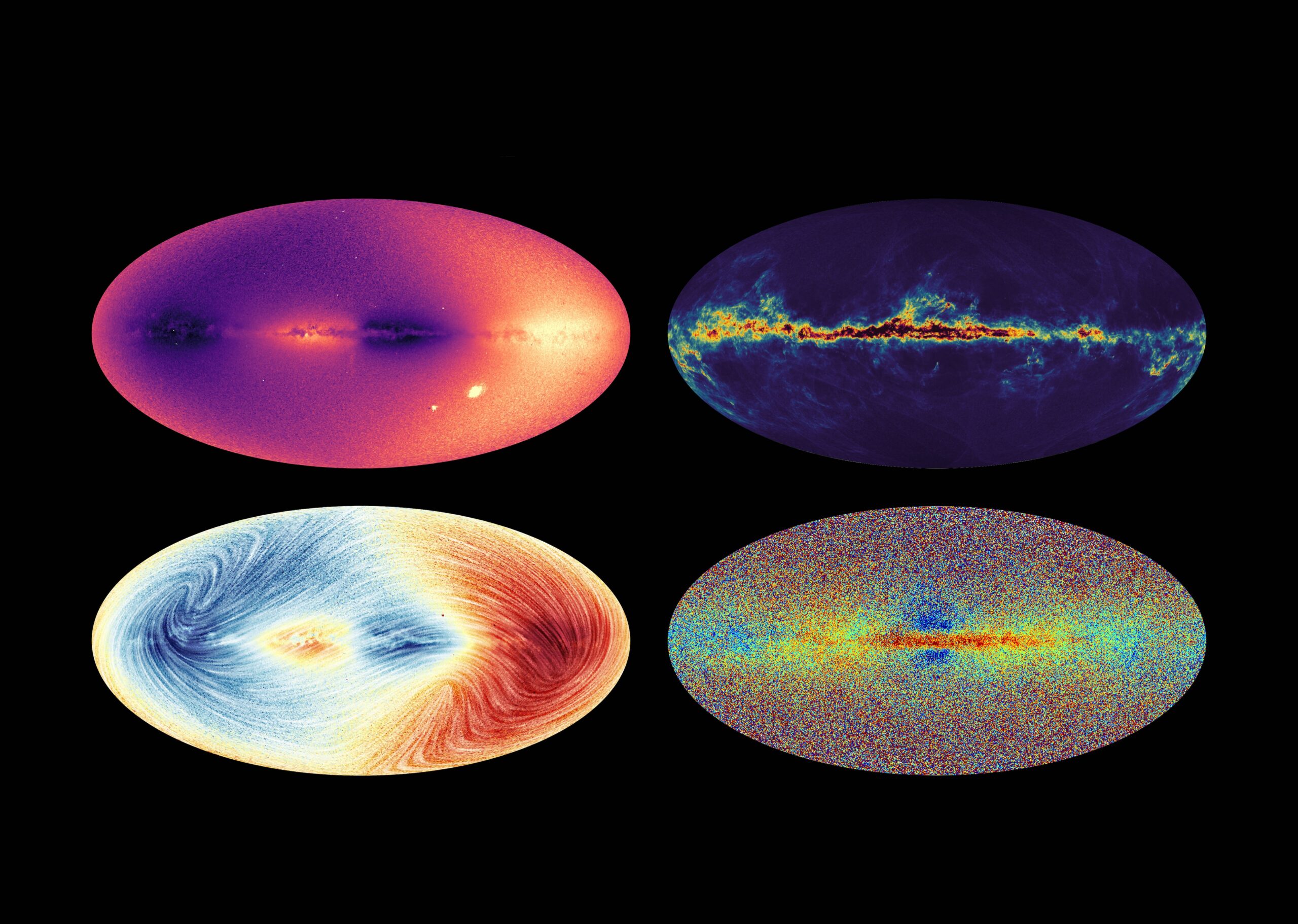

These four sky maps show off Gaia data released in June 2022 (Data Release 3). At upper left, a map of radial velocity shows the motion of stars toward or away from Earth, with darker colors moving toward us and brighter colors moving away from us. The map below it (lower left) also shows motion toward (blue) and away (red) from Earth, this time combined with stars’ proper motion — their projected motion across the sky — shown as the white lines. This combination of details allows astronomers to see how stars in different parts of the galaxy are moving in both speed and direction. The oval at upper right is Gaia’s map of interstellar dust in our galaxy, showing not starlight but where that light is absorbed. Blacker regions along the center — the plane of the Milky Way — indicate more absorption (and more dust), while brighter colors show where there is less absorption (and less dust). The dark blue regions at the top and bottom of the oval map show where there is very little dust. At bottom right is a chemical map of the Milky Way, revealing stars that contain higher concentrations of metals (redder colors); bluer colors are stars with fewer metals. Astronomers consider any elements heavier than hydrogen and helium to be metals. Older stars have fewer metals than more recent generations of suns.

Not done yet

The most recent data release, Data Release 3, was in 2022; two more are expected, in 2026 and around 2030. The release in 2026 will cover five and a half years of data. In addition to the longer timespan, the Gaia team has improved instrument calibration and algorithms for processing the data, meaning the next batch of data will be even cleaner and more precise.

Sahlmann notes that this release will also include the individual measurements for 2 billion sources, instead of the more processed data of the earlier releases: “These will allow the data users to perform their own sophisticated analyses of these data, which so far has mostly been the realm of the Gaia consortium internal processing.”

That 2026 data release will also include a large exoplanet candidate catalog, which has been a long time coming. When Gaia launched, astronomers predicted the telescope might find as many as 21,000 exoplanets during five years of observations. So far, the entire count from all of history stands at just over 6,000, so a jump this large would revolutionize the field.

That jump also makes sense — Gaia’s steady eyes on the sky are similar to the way the Kepler telescope scanned for exoplanets, and Kepler transformed exoplanet science with a catalog of just 150,000 stars. But while Kepler watched for stars to dim as a planet passed across its surface, Gaia will see the tiny motion of the star as a planet tugs on it during its orbit.

With the full 10 and a half years of observations, astronomers predict a haul of some 70,000 exoplanets, as well as exquisite precision when it comes to the overall mapping of stars in our galaxy. That data release won’t happen until at least the end of the decade, around 2030 or later.

The long waits are due to the massive amounts of data — about a petabyte, or a million gigabytes, in the full dataset. All that data takes an immense amount of processing to untangle the minuscule shifts of stars on the sky from any noise from space or the telescope itself. It’s a fine process, but it will be worth the wait.

“Gaia is now no longer acquiring new scientific data,” Sahlmann says, “but in terms of the scientific exploration of the Gaia data, we remain only at the beginning. The most exciting discoveries still lie ahead of us and the Gaia mission catalogs have already become a new backbone for observational astronomy.”