The solar system’s two largest planets adorn the evening sky this month, while the smaller inner planets linger near the Sun and remain mostly out of sight.

You’ll want to make Saturn your first target as darkness descends. The ringed planet shines at magnitude 1.0 and appears low in the west among the faint background stars of Pisces the Fish. Although Saturn stands 46° east of the Sun in early February, the ecliptic makes a shallow angle to the western horizon from mid-southern latitudes at sunset this time of year, so the planet hangs low in our sky.

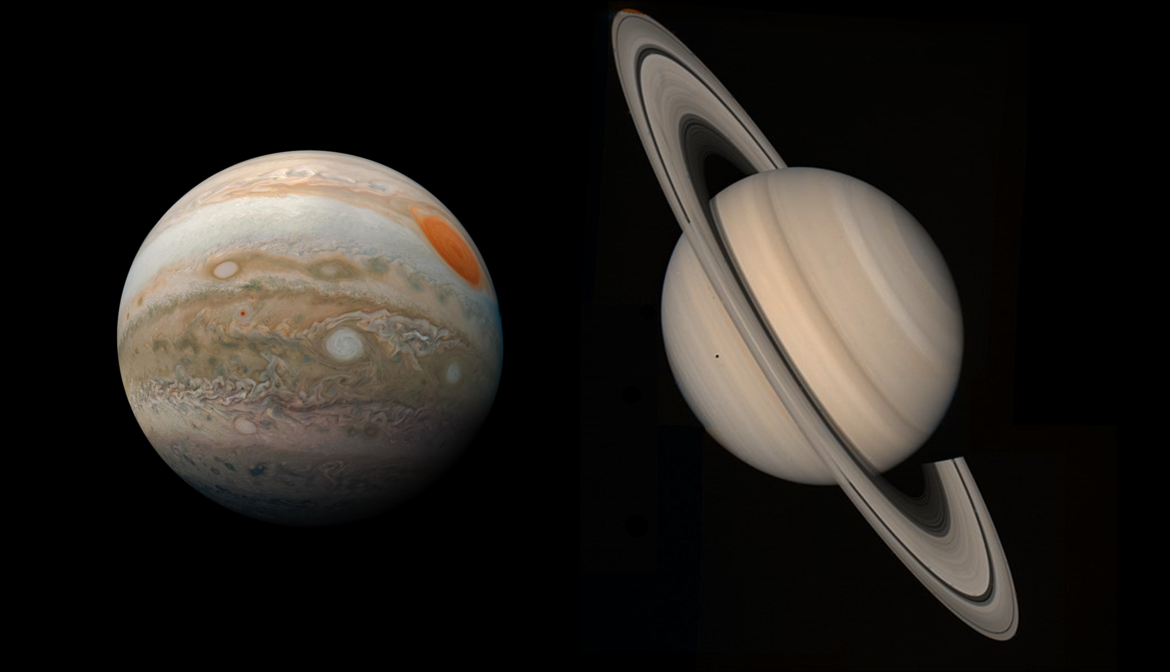

The best views through a telescope come during fleeting moments of steady seeing. In mid-February, Saturn’s disk measures 16″ across while the rings span 37″ and tilt 3° to our line of sight. Also look for the planet’s largest satellite, 8th-magnitude Titan, which completes an orbit of the giant world every 16 days.

Saturn serves as a convenient guide to the outermost major planet around midmonth. On the 16th, the ringed world passes 0.9° south (upper left) of Neptune. You should be able to spot the 8th-magnitude planet through a small scope.

Magnitude –2.5 Jupiter stands as the brightest object in February’s evening sky. The giant planet appears in the northeast as twilight fades to darkness. It moves slowly westward against the backdrop of central Gemini, some 10° above the Twins’ brightest stars, Castor and Pollux.

A telescope resolves fine detail in the gas giant’s atmospheric bands. The best views come when it climbs highest in the north during the late evening hours. Look for two parallel dark belts, one on either side of a brighter zone that coincides with Jupiter’s equator, which spans 44″ in mid-February. The planet’s four bright moons should also stand out on any clear evening.

Earth’s three closest planetary neighbors fare far worse than their more distant siblings. Venus crawls slowly away from the Sun into the evening sky while Mars does the same in the morning sky. Yet neither achieves a significant elongation by month’s end. Venus then stands 13° from the Sun and Mars is only 12° from our star.

Mercury reaches greatest elongation Feb. 19, when it lies 18° east of the Sun but appears just 3° above the western horizon 30 minutes after sunset from mid-southern latitudes. It will be a bit higher if you live closer to the equator.

An annular solar eclipse occurs Feb. 17, though most observers of the event will be penguins because the path makes landfall only in Antarctica. The center line passes about 500 kilometers east of Australia’s Davis Station. Those hardy souls in Davis can see a partial eclipse. Maximum occurs at 12h04m UT, when the Moon obscures 95 percent of the Sun’s diameter. Residents in southeastern Africa and the southern tip of South America will witness a lesser partial eclipse. Wherever you are, be sure to use a safe solar filter to view the event.

The starry sky

The wonderful Orion the Hunter ranks among the showpiece star patterns in the entire sky. It contains several prominent stars as well as one of the finest star-forming regions — the great Orion Nebula (M42) — to explore with a small telescope. The constellation climbs high in the north in February’s early evening sky.

Orion’s two brightest stars, blue-white Rigel and reddish Betelgeuse, vie for attention because of their brilliance and contrasting colors. But this month I want to highlight the Hunter’s other two corner stars: Bellatrix and Saiph.

From our point of view, Bellatrix (Gamma [γ] Orionis) lies at the lower left of the main group of stars and marks one of the giant’s shoulders. It has a mass about 8.5 times that of the Sun and shows a spectral type of B2. Compare its blue-white color with ruddy Betelgeuse, which lies 7.5° to the east (right).

Although Bellatrix appears to be a single star, some researchers suspect it has a stellar companion. Gamma glows at magnitude 1.6, and for a long time astronomers thought it shone steadily. That made it a convenient “standard star” for UBV photometry (the measurement of stellar brightness in the three spectral bands of ultraviolet, blue, and visible light). Indeed, it was on that list when I put together photometric equipment for Tasmania’s largest telescope in the 1970s. However, scientists have since found that it varies slightly in brightness between magnitudes 1.59 and 1.64.

If you jump diagonally across Orion to the upper right, you’ll pass by the three conspicuous stars of Orion’s Belt and then come to magnitude 2.1 Saiph (Kappa [κ] Ori), which marks one of the Hunter’s legs. Saiph is the southernmost of Orion’s bright stars and stands only 1° north of the constellation’s border with Lepus the Hare.

Although Kappa appears half a magnitude dimmer than Bellatrix, that’s a little misleading. If you compare the two star’s intrinsic brightnesses, Saiph is the real standout. Astronomers use absolute magnitude, the apparent brightness a star would have if it were 10 parsecs (32.6 light-years) away from us, to measure true luminosity. On this scale, Bellatrix shines at magnitude –2.8 while Saiph, a blue supergiant with about 15 times the Sun’s mass, gleams at magnitude –6.1, or some 21 times brighter. If Saiph were only 10 parsecs away, it would be obvious in broad daylight and outshine Venus by at least 1.5 magnitudes.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 30° south latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

10 p.m. February 1

9 p.m. February 15

8 p.m. February 28

Planets are shown at midmonth