By the 1960s, astronomers were increasingly eying long-baseline interferometry — using multiple telescopes spread across wide geographical areas to yield the observing power of a single detector — as a tool to scrutinize the galactic center. A key player in this emerging arena of inquiry was the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) site at Green Bank in West Virginia. Its three telescopes, each spanning 85 feet (26 meters), were teamed with a 45-foot (14 m) mountaintop telescope 22 miles (35 km) away in Huntersville, creating a tenfold increase in resolution.

In June 1972, astronomers Dennis Downes and Miller Goss, then working at West Germany’s Max Planck Institute, submitted a proposal to the NRAO to observe the galactic center. But trouble obtaining travel funds prevented them from visiting the U.S., and astronomers Bruce Balick, later of the University of Washington, and Robert Brown of NRAO tendered their own bid to investigate star-forming regions near the Milky Way’s heart. Early in 1974, they observed Sagittarius B2, a giant molecular cloud 390 light-years from the galactic center, but discerned no bright stars.

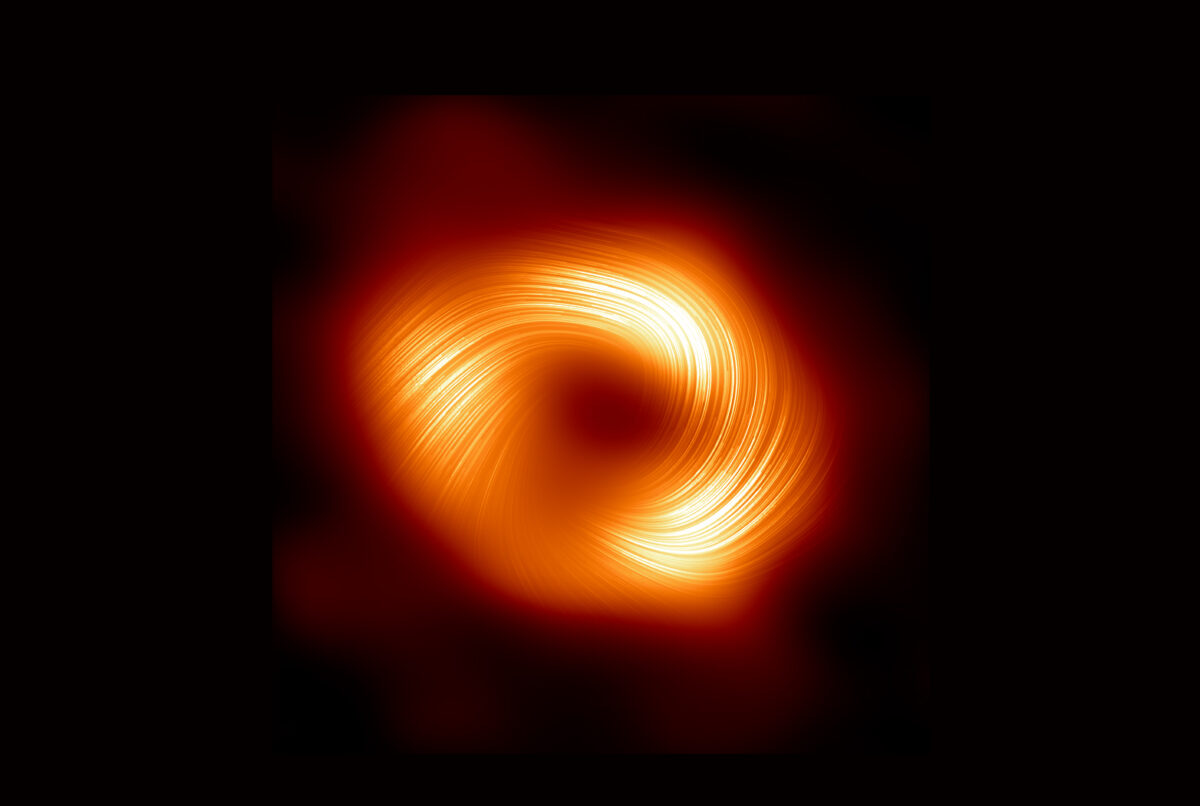

Then – “for the hell of it,” Balick later recounted in 2022 interview with Mashable – on Feb. 13-15 they turned the Green Bank instruments onto the galactic center itself. They detected a sub-arcsecond source that exhibited an intense radio signal, much more powerful than expected.

It was a thrilling moment, said Balick: peering across 26,000 light-years to spy the glow of the Milky Way’s pulsating heart as it appeared when Neanderthals walked on Earth. Their six-page paper, “Intense Sub-Arcsecond Structure in the Galactic Center,” graced the Astrophysical Journal in December 1974. The object’s nature as a black hole – named Sagittarius A* (pronounced “Sagittarius A-star” and abbreviated Sgr A*) – took another quarter-century to prove.