Key Takeaways:

- Rising launch cadences have dramatically increased orbital debris, posing critical risks to spacecraft and operations, as highlighted by incidents like the Shenzhou-21 stranding.

- The primary barrier to addressing space debris is economic, as current models lack incentives for remediators who bear all costs while space operators benefit from a cleaner environment without financial contribution.

- A recent study employs game theory to propose a commercially viable framework for debris remediation, suggesting a regulatory body collect fees from operators (based on avoided costs) and distribute incentives to remediators via a Nash bargaining solution.

- Of the three remediation methods analyzed, uncontrolled reentry is deemed the most commercially viable near-term solution due to its lower operational costs, whereas controlled reentry incurs higher expenses, and orbital recycling is currently economically unfeasible.

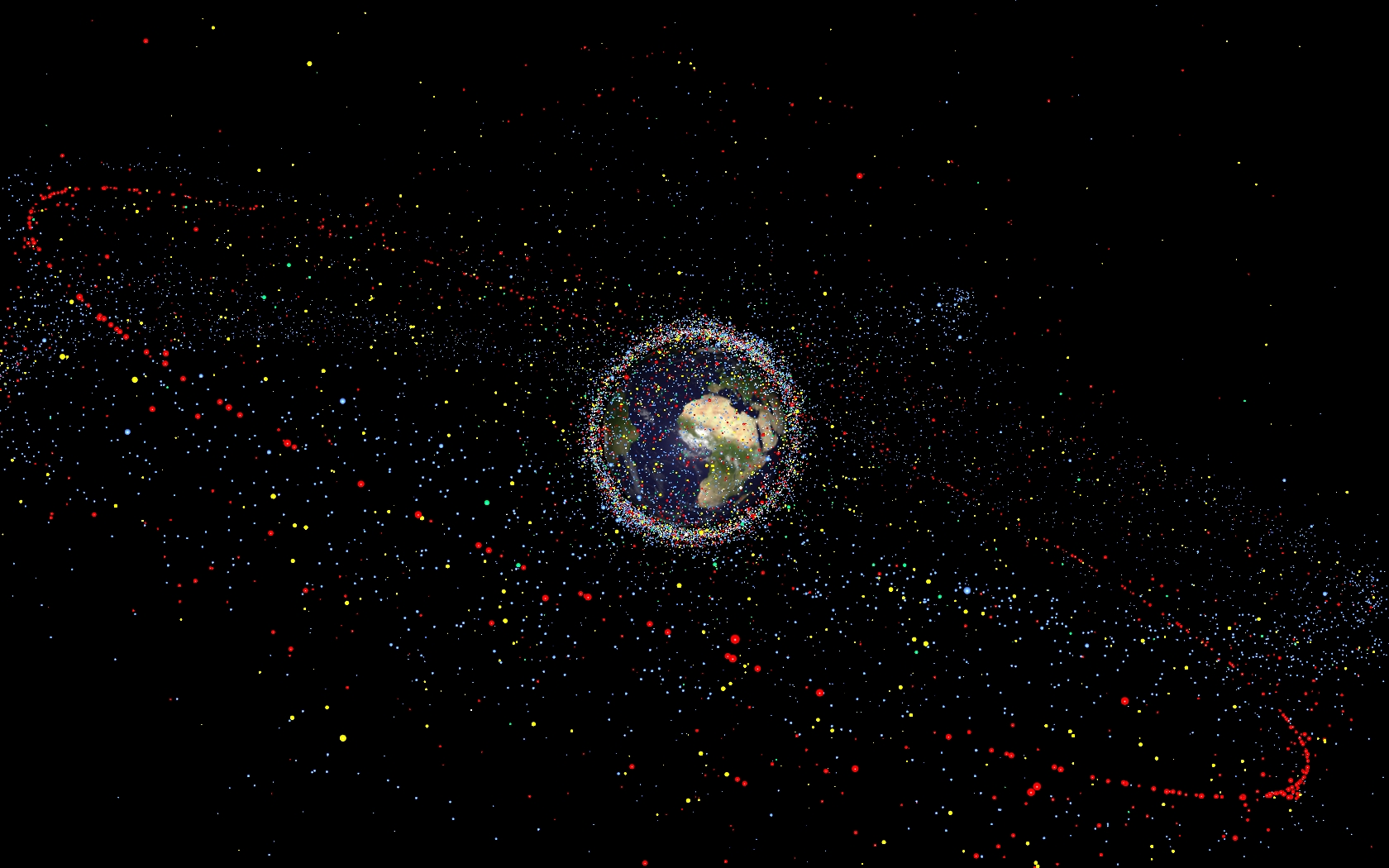

The recent stranding of the Shenzhou-21 crew, caused by debris damage to the Shenzhou-20 return capsule, underscores the practical risks of an increasingly crowded low Earth orbit. With launch cadences nearly 12 times higher in 2024 than in 2014, the volume of debris in orbit traveling at dangerous speeds will only continue to grow, threatening astronauts, active satellites, and future launches.

Despite European Space Agency (ESA) estimates of over 44,000 large debris objects currently in orbit (in addition to hundreds of millions of smaller objects), the high cost of removal has prevented any country or company from addressing the problem. In a study published Oct. 5 in the Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, researchers at the Stevens Institute of Technology explore options for making the removal of space debris commercially viable. By applying game theory to the logistics and economics of satellite launches, the study outlines potential solutions that benefit both spacecraft operators and debris remediators.

“That is what’s needed to move us closer to a space industry that is safer, more sustainable, and still profitable,” said Hao Chen, a study co-author and assistant professor at Stevens Institute of Technology, in a press release.

A lack of incentives

While the physical dangers of space debris are well-documented, the authors argue that the primary barrier to cleanup is economic. The study notes that “while multiple recent cost-benefit studies illuminate the economic value of orbital debris remediation, the relationship established between space operators and debris remediators is one-sided.”

Currently, “debris remediators bear all the cost of removal, while space operators get to enjoy the benefits of an improved operating environment,” the authors note; commercial entities and government agencies operating satellites gain from a safer orbit, but they have no financial reason to pay for it. Conversely, private companies capable of removing debris bear all the operational costs — including fuel, launch, and technology development — with no guaranteed benefit in exchange for their investments.

RELATED: Satellite megaconstellations: Not just a problem from Earth anymore

The new study attempts to solve the problem by modeling the economic impact of debris-removal missions using game theory — a field of mathematics used in economics, logic, and computer science for determining mutually beneficial and strategic outcomes in complex scenarios. Specifically, the researchers modeled a cooperative game played between two parties: space operators and debris remediators.

The goal of the game is to find a way to access the financial value hidden in debris remediation. The researchers argue that removing a piece of debris generates value in the form of avoided costs for the operators. Every time a satellite operator does not have to pay to track a piece of junk, maneuver to avoid it, or replace a satellite lost to a collision, money is saved. By estimating these avoided costs over 10 years for the top 50 most dangerous objects, the team calculated the total financial benefit of cleaning them up.

They then compared this potential value against the actual cost of launching a remediation mission. To determine if a surplus could be generated, they modeled the specific costs for three different removal methods.

However, the authors note that the two parties cannot easily access this surplus on their own; their framework relies on a regulatory entity to act as a mediator. This entity would be responsible for collecting fees from the operators based on the savings they enjoy and distributing those funds as incentives to the remediators. To determine the most fair and profitable way to split this money, the researchers applied a “Nash bargaining solution” — a game theory concept used to find a win-win scenario where the total value created is maximized and shared, ensuring neither side has a reason to walk away from the deal.

Controlled reentry

The researchers analyzed the costs and benefits of three specific removal methods. The first, controlled reentry, offers the highest level of safety and precision. In this scenario, a remediator spacecraft captures a piece of debris and transports it down to an altitude of 31 miles (50 kilometers). From there, the object is released to burn up in the atmosphere over a specific, unpopulated target zone.

While this method ensures that no falling debris threatens infrastructure or populations on Earth, it is operationally expensive. The study found that the high fuel requirements needed to push debris to such a low altitude significantly drive up mission costs. Consequently, the economic surplus — the profit margin available to be shared between the operator and the cleaner — is smaller compared to less fuel-intensive methods.

Uncontrolled reentry

The second method modeled was uncontrolled reentry. Here, the servicer captures the debris but only lowers it to a circular orbit of 217.5 miles (350 km). At this altitude, atmospheric drag will naturally cause the object to decay and burn up over time, though without precise control over where any surviving fragments might land.

The study identified this approach as the most commercially viable option in the near term. Because the servicer does not need to descend as deeply into the atmosphere, it saves significant amounts of propellant. The researchers found that this method yielded the widest range of profitable deal structures — a variety of fee and incentive configurations where both the operator and the remediator could turn a profit. The lower operational overhead means a deal is easier to strike, making it an attractive starting point for a commercial remediation industry.

Orbital recycling

The third and most futuristic solution proposed is orbital recycling. In this model, debris is not de-orbited but transported to a space-based recycling center. There, extracted metals could be repurposed for manufacturing purposes or refined into fuel.

While theoretically appealing, the study found this method to be the least economically feasible with current technology. The logistics of moving heavy debris to a specific recycling station require massive fuel consumption, often doubling the cost compared to reentry methods. The study noted that for recycling to become viable, the process must be highly efficient — recovering at least 65 percent of the debris mass — and the value of the recycled materials must be high enough to offset the extreme transportation costs.

A surplus exists

The study ultimately finds that the financial value of less debris exceeds the cost of cleaning it up. However, this theoretical surplus can only be transformed into revenue for remediators if a regulatory body implements a fee structure to collect that value from operators and redistribute it. While recycling remains a long-term ambition, the researchers suggest that a market based on uncontrolled reentry could function today if these regulatory frameworks are put in place.

“We will need some agency to create an incentive for the debris remediators,” said Chen. “The money should come from the people who enjoy all those benefits. Our analysis shows that there is a surplus to be generated from the remediation of orbital debris, and that surplus can be optimally shared by space operators and debris remediators.”