Key Takeaways:

- Hypervelocity stars (HVS) are celestial bodies moving at speeds sufficient to escape the Milky Way's gravitational pull, with a primary proposed origin involving binary star interactions with the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A*.

- A distinct concentration of HVS in the constellations Leo and Sextans suggests an alternative origin, with a 2017 study proposing their ejection from binary systems within the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC).

- This LMC ejection mechanism occurs when one star in a binary system explodes as a supernova, imparting its orbital velocity to the companion star, which combines with the LMC's own velocity to achieve hypervelocity.

- During a supernova event, a companion star's self-gravity typically preserves its bulk, preventing physical destruction despite potential loss of outer layers, often resulting in the formation of X-ray binaries.

In 2017, astronomers found hypervelocity stars believed to have come from the Large Magellanic Cloud, supposedly kicked out of binary systems by supernovae. What kept the surviving star from being destroyed by the blast?

Launie Wellman

Festus, Missouri

Some stars in our galaxy, known as hypervelocity stars, move much faster than most other stars in the Milky Way. In fact, they are traveling so fast that our galaxy’s gravity can’t hold onto them and eventually they will escape into intergalactic space, never to return.

Scientists believe many hypervelocity stars are flung out when two stars orbiting each other (a binary star system) get too close to the enormous black hole at the center of the Milky Way, called Sagittarius A*. The black hole’s powerful gravity can tear the pair apart, capturing one star while slingshotting the other away at thousands of miles per second — far faster than our Sun’s orbital speed of nearly 140 miles (220 kilometers) per second.

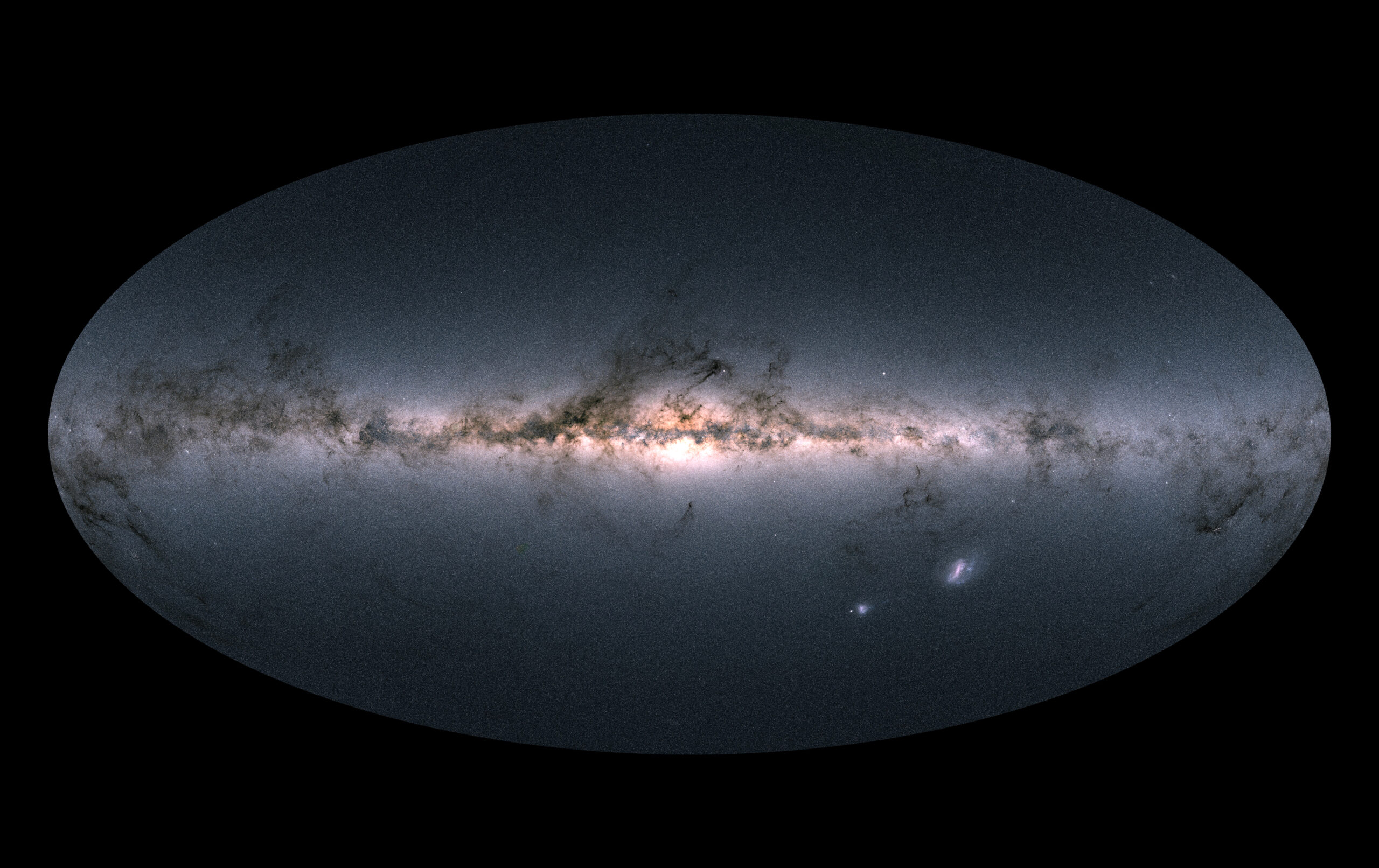

If all hypervelocity stars came from the center of the Milky Way in this way, we’d expect to see them scattered evenly across the sky. However, a surprising number have been found in one particular area: the constellations Leo and Sextans. A 2017 study suggested that those hypervelocity stars may have been ejected from a different source: the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a small neighboring galaxy orbiting the Milky Way.

This could happen if one star in a binary system explodes as a supernova. Normally, binary stars orbit each other at high speeds to avoid crashing. But when one star explodes, the other can fly away at its orbital speed. Since the LMC itself is moving at 250 miles (400 km) per second, depending on the ejected star’s direction, its speed (as seen by us) could add up to match that of hypervelocity stars caused by interactions with Sagittarius A*. And we’d see them all in the area of Leo and Sextans because the stars are ejected along the orbit of the LMC, which flings them in the direction of these particular constellations.

Interestingly, when a supernova explodes, it doesn’t destroy its companion star — or any planets that might be orbiting it. While a nearby supernova would be dangerous to life on Earth by damaging our atmosphere with high-energy radiation, it wouldn’t physically destroy the planet. Similarly, a companion star might lose some of its outer layers due to a nearby supernova, but the star’s self-gravity keeps the bulk of it intact. In fact, many binary stars stay together even after a supernova, forming what are known as X-ray binaries, where a normal star orbits a dense neutron star or black hole that formed from the core of the star that exploded as a supernova. In such X-ray binaries, the strong gravitational tides from the neutron star or black hole rip off the outer layers of the normal companion, creating an accretion disk that glows in X-rays. The Milky Way is teeming with such X-ray binaries.

Monica Valluri

Research Professor of Astronomy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan